Hinduism is the oldest religion in the world, originating in Central Asia and the Indus Valley, still practiced in the present day. The term Hinduism is what is known as an exonym (a name given by others to a people, place, or concept) and derives from the Persian term Sindus designating those who lived across the Indus River.

Adherents of the faith know it as Sanatan Dharma (“eternal order” or “eternal path”) and understand the precepts, as set down in the scriptures known as the Vedas, as having always existed just as Brahman, the Supreme Over-Soul from whom all of creation emerges, has always been. Brahman is the First Cause which sets all else in motion but is also that which is in motion, that which guides the course of creation, and creation itself.

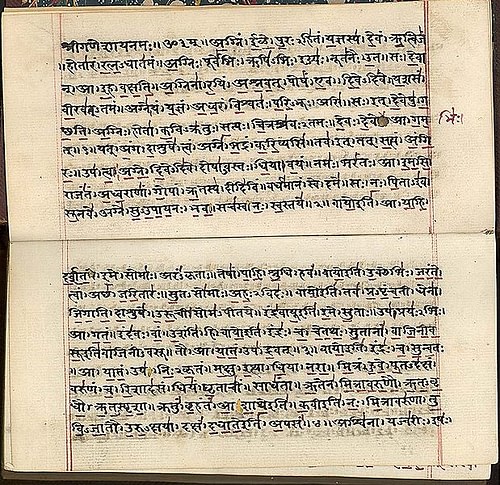

Accordingly, one may interpret Hinduism as monotheistic (as there is one god), polytheistic (as there are many avatars of the one god), henotheistic (as one may choose to elevate any one of these avatars to supremacy), pantheistic (as the avatars might be interpreted as representing aspects of the natural world), or even atheistic as one might choose to replace the concept of Brahman with one's self in striving to be the best version of one's self. This belief system was first set down in writing in the works known as the Vedas during the so-called Vedic Period c. 1500 to c. 500 BCE but the concepts were transmitted orally long before.

There is no founder of Hinduism, no date of origin, nor – according to the faith – a development of the belief system; the scribes who wrote the Vedas are said to have been simply recording that which had always existed. This eternal knowledge is known as shruti (“what is heard”) and is set down in the Vedas and their various sections known as the Samhitas, Aranyakas, Brahmanas, and, most famously, the Upanishads, each of which addresses a different aspect of the faith.

These works are complemented by another type known as smritis (“what is remembered”) which relate stories on how one is to practice the faith and include the Puranas, the epics Mahabharata and Ramayana, the Yoga Sutras, and the Bhagavad Gita. None of these, however, should be considered the “Hindu Bible” as there is no claim they are the “word of God”; they are, instead, the revelation of the truth of existence which claims the universe is rational, structured, and controlled by the Supreme OverSoul/Mind known as Brahman in whose essence all human beings take part.

The purpose of life is to recognize the essential oneness of existence, the higher aspect of the individual self (known as the Atman) which is a part of everyone else's self as well as the Over-Soul/Mind and, through adherence to one's duty in life (dharma) performed with the proper action (karma), to slip the bonds of physical existence and escape from the cycle of rebirth and death (samsara). Once the individual has done so, the Atman joins with Brahman and one has returned home to the primordial oneness.

That which keeps one from realizing this oneness is the illusion of duality – the belief that one is separate from others and from one's Creator – but this misconception (known as maya), encouraged by one's experience in the physical world, may be overcome by recognizing the essential unity of all existence – how alike one is to others and, finally, to the divine – and attaining the enlighted state of self-actualization.

Early Development

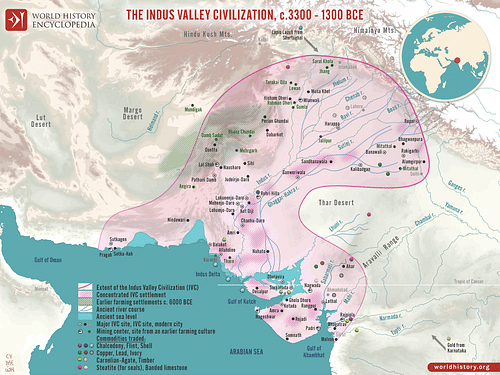

Some form of the belief system which would become, or at least influence, Hinduism most likely existed in the Indus Valley prior to the 3rd millennium BCE when a nomadic coalition of tribes who referred to themselves as Aryan came to the region from Central Asia. Some of these people, now referred to as Indo-Iranians, settled in the region of modern-day Iran (some of whom came to be known in the West as Persians) while others, now known as Indo-Aryans, made their home in the Indus Valley. The term Aryan referred to a class of people, not a race, and meant “free man” or “noble”. The long-standing myth of an “Aryan Invasion” in which Caucasians “brought civilization” to the region is the product of narrow-minded and prejudiced 18th- and 19th-century Western scholarship and has long been discredited.

It is clear from the ruins of cities such as Mohenjo-daro and Harappa (to name only the two most famous) that a highly advanced civilization was already well developed in the Indus River Valley by c. 3000 BCE, having grown from Neolithic Period settlements dating to before 7000 BCE. This period is now referred to as the era of the Indus Valley Civilization or the Harappan Civilization (c. 7000 to c. 600 BCE) which would be influenced by and merge with the culture of the Indo-Aryans.

By c. 2000 BCE, the great city of Mohenjo-daro had brick streets, running water, and a highly developed industrial, commercial, and political system. It is almost certain they also had developed some sort of religious belief which included ritual bathing and other religious observances, but no written records exist to substantiate this. It is more certain that, whatever form this religion took, significant elements of it originated elsewhere as the basic Vedic thought (as well as the names and characters of many of the gods) correspond closely with the Early Iranian Religion of Persia.

The early Indus Valley religion developed through the influence of the new arrivals during the Vedic Period. During this time, the belief system known as Vedism was developed by the so-called Vedic peoples who wrote in Sanskrit, the language the Vedas are composed in. Scholar John M. Koller writes:

The Sanskrit language, of which the Vedas are the oldest surviving expression, became dominant. Although the Sanskrit tradition reflects borrowing and accommodations from non-Vedic sources, it hides more of these contributions than it reveals. Thus, despite the grandeur of the ancient Indus civilization, it is to the Vedas that we must turn for an understanding of earliest Indian thought. (16)

The Vedas sought to understand the nature of existence and the individual's place in the cosmic order. In pursuing these questions, the sages created the highly developed theological system which would become Hinduism.

Brahmanism

Vedism became Brahmanism, a religious belief focusing on the underlying Truth, the First Cause, of all observable phenomena as well as the unseen aspects of existence. The sages who developed Brahmanism began with the observable world which operated according to certain rules. They called these rules rita (“order”) and recognized that, in order for rita to exist, something had to have existed previously to create it; one could not have rules without a rule-maker.

At this time, there were many gods in the pantheon of Vedism who could have been looked to as the First Cause but the sages went beyond the anthropomorphic deities and recognized, as Koller puts it, that “there is a wholeness, an undivided reality, that is more fundamental than being or non-being” (19). This entity was envisioned as an individual but one so great and powerful as to be beyond all human comprehension.

The being they came to refer to as Brahman did not just exist in reality (another being like any others) nor outside of reality (in the realm of non-being or pre-existence) but was actual reality itself. Brahman not only caused things to be as they were; it was things as they were, had always been, and would always be. Hence the designation of Sanatan Dharma – Eternal Order – as the name of the belief system.

If that were so, however, an insignificant individual living briefly on the earth had no hope of connection with this ultimate source of life. Since Brahman could not be comprehended, no relationship could be possible. The Vedic sages turned their attention from the First Cause to the individual and defined the aspects of the self as the physical body, as the soul, and as the mind but none of these were adequate to make a connection to the Ultimate until they understood there had to be a higher self which directed one's other functions. Koller comments:

This Self is said to be “other than the known and other than the unknown” [Kena Upanishad I.4]. The question the sage is asking is: What makes possible seeing, hearing, and thinking? But the question is not about physiological or mental processes; it is about the ultimate subject who knows. Who directs the eye to see color and the mind to think thoughts? The sage assumes there must be an inner director, an inner agent, directing the various functions of knowledge. (24)

This “inner director” was determined to be the Atman – one's higher self – who is connected to Brahman because it is Brahman. Every individual carries within themselves the Ultimate Truth and the First Cause. There is no reason to seek this entity externally because one carries that entity inside of one's self; one only has to realize this truth in order to live it; as expressed in the Chandogya Upanishad in the phrase Tat Tvam Asi – “Thou Art That” – one is already what one seeks to become; one only has to realize it.

This realization was encouraged through rituals which not only celebrated Brahman but reenacted the creation of all things. The priestly class (Brahmins), in elevating the Ultimate Divine through the chants, hymns, and songs of the Vedas, elevated an audience by impressing upon them the fact that they already were where they wanted to be, they were not just in the presence of the Divine but were an integral part of it, and all they needed to do was be aware of this and celebrate it through performance of their divinely-appointed duty in life enacted according to that duty.

Classical Hinduism

Brahmanism developed into the system now known as Hinduism which, although generally regarded as a religion, is also considered a way of life and a philosophy. The central focus of Hinduism, whatever form one believes it takes, is self-knowledge; in knowing one's self, one comes to know God.

Evil comes from ignorance of what is good; knowledge of what is good negates evil. One's purpose in life is to recognize what is good and pursue it according to one's particular duty (dharma), and the action involved in that proper pursuit is one's karma. The more dutifully one performs one's karma in accordance with one's dharma, the closer to self-actualization one becomes and so the closer to realizing the Divine in one's self.

The physical world is an illusion only in so far that it convinces one of duality and separation. One may turn one's back on the world and pursue the life of a religious ascetic, but Hinduism encourages full participation in life through the purusharthas – life goals – which are:

- Artha – one's career, home life, material wealth

- Kama – love, sexuality, sensuality, pleasure

- Moksha – liberation, freedom, enlightenment, self-actualization

The soul takes enjoyment in these pursuits even though it understands they are all temporal pleasures. The soul is immortal – it has always existed as part of Brahman and will always exist – therefore the finality of death is an illusion. At death, the soul discards the body and then is reincarnated if it failed to attain Moksha or, if it did, the Atman becomes one with Brahman and returns to its eternal home. The cycle of rebirth and death, known as samsara, will continue until the soul has had its fill of earthly experience and pleasures and concentrates a life on detachment and pursuit of eternal, rather than temporal, goods.

Helping or hindering one in this goal are three qualities or characteristics inherent in every soul known as the gunas:

- Sattva – wisdom, goodness, detached enlightenment

- Rajas – passionate intensity, constant activity, aggression

- Tamas – literally “blown by the winds”, darkness, confusion, helplessness

The gunas are not three states one 'works through' from lowest to highest; they are present in every soul to greater or lesser degrees. An individual who is generally composed and lives a good life might still become swept away by passion or find themselves whirling in helpless confusion. Recognizing the gunas for what they are, however, and working to control the less desirable aspects of them, helps one to see more clearly one's dharma in life and how to perform it. One's dharma can only be performed by one's self; no one may perform another's duty. Everyone has arrived on the earth with a specific role to play and, if one chooses not to play that role in one's present life, one will come back in another and another until one does so.

This process is often related to the Caste System of Hinduism in which one is born to a certain station which one cannot in any way change, must perform one's designated function as part of that class for life, and will be reincarnated if one fails to perform correctly. This concept, contrary to popular thought, was not imposed on the people of India by the colonial government of Britain in the 19th century but was first suggested in the Bhagavad Gita (composed c. 5th-2nd centuries BCE) when Krishna tells Arjuna about the gunas and one's responsibility to one's dharma.

Krishna says that one must do what one is supposed to do and relates the varna (caste) system as part of this in describing how an individual should live one's life according to Divine Will; anyone could be a Brahmin or a warrior or a merchant if that was their dharma; the caste system exists within each individual just as the gunas do. Krishna's words were later revised in the work known as Manusmriti (“The Laws of Manu”), written in the 2nd century BCE to the 3rd CE, which claimed a strict caste system had been ordained as part of the Divine Order in which one was destined to remain, for life, in the social class one was born into. The Laws of Manu manuscript is the first expression of this concept as it has now come to be understood.

Texts & Observance

Manu's later interference aside, the concept of Eternal Order is made clear through the texts which are regarded as the Hindu scriptures. These works, as noted, fall into two classes:

- Shruti (“what is heard”) – the revelation of the nature of existence as recorded by the scribes who “heard” it and recorded it in the Vedas.

- Smritis (“what is remembered”) – accounts of great heroes of the past and how they lived – or failed to live – in accordance with the precepts of Eternal Order.

The texts relating Shruti are the Four Vedas:

- Rig Veda – the oldest of the Vedas, a collection of hymns

- Sama Veda – liturgical texts, chants, and songs

- Yajur Veda – ritual formulas, mantras, chants

- Atharva Veda – spells, chants, hymns, prayers

Each of these is further divided into types of text:

- Aranyakas – rituals, observances

- Brahmanas – commentaries on said rituals and observances explaining them

- Samhitas – benedictions, prayers, mantras

- Upanishads – philosophical commentaries on the meaning of life and Vedas

The texts relating Smritis are:

- Puranas – folklore and legend regarding figures of the ancient past

- Ramayana – epic tale of Prince Rama and his journey to self-actualization

- Mahabharata – epic tale of the five Pandavas and their war with the Kauravas

- Bhagavad Gita – popular tale in which Krishna instructs the prince Arjuna on dharma

- Yoga Sutras – commentary on the different disciplines of yoga and self-liberation

These texts allude to or specifically address numerous deities such as Indra, lord of the cosmic forces, thunderbolts, storms, war, and courage; Vac, goddess of consciousness, speech, and clear communication; Agni, god of fire and illumination; Kali, goddess of death; Ganesh, the elephant-headed god, remover of obstacles; Parvati, goddess of love, fertility, and strength and also the consort of Shiva; and Soma, god of the sea, fertility, illumination, and ecstasy. Among the most important of the deities are those who make up the so-called “Hindu Trinity”:

All of these gods are manifestations of Brahman, the Ultimate Reality, who can only be understood through aspects of Itself. Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva are both these aspects and individual deities with their own characters, motivations, and desires. They may also be understood through their own avatars – as they themselves are also too overwhelming to be comprehended on their own entirely – and so take the form of other gods, the most famous of which is Krishna, the avatar of Vishnu, who comes to earth periodically to adjust humanity's understanding and correct error.

In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna appears as the Prince Arjuna's charioteer because he knows Arjuna will have doubts about fighting against his relatives at the Battle of Kurukshetra. He pauses time in order to instruct Arjuna on the nature of dharma and the illusion of the finality of death, elevating his mind above his interpretation of present circumstance, and allowing him to perform his duty as a warrior.

These texts inform the religious observances of adherents of Sanatan Dharma which, generally speaking, have two aspects:

- Puja – worship, ritual, sacrifice, and prayer either at a personal shrine or temple

- Darshan – direct visual contact with the statue of a deity

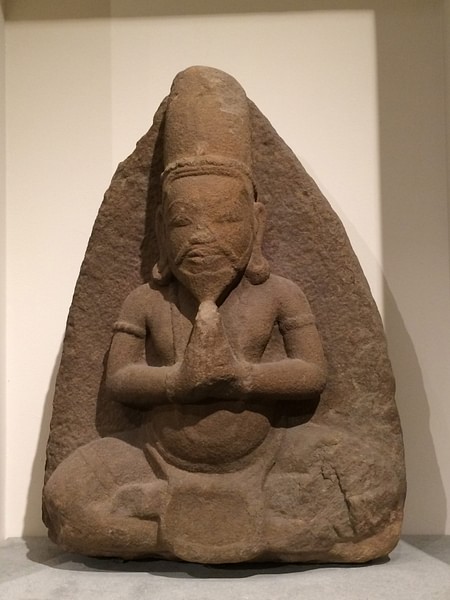

One may worship the Divine at one's home, a personal shrine, or a temple. In the temple, the clergy will assist an individual and their family by interceding on their behalf with the deity by instruction, chants, songs, and prayers. Song, dance, and general movement in expressing one's self before God often characterize a religious service. An important element of this is visual contact with the eyes of the deity as represented by a statue or figurine.

Darshan is vital to worship and communion in that the god is seeking the adherent as earnestly as the adherent seeks the deity and they meet through the eyes. This is the reason why Hindu temples are adorned with figures of the many gods both inside and externally. The statue is thought to embody the deity itself and one receives blessings and comfort through eye contact just as one would in a meeting with a friend.

Conclusion

This relationship between a believer and the deity is most apparent through the many festivals observed throughout the year. Among the most popular is Diwali, the festival of lights, which celebrates the triumph of bright energies and light over the forces of negativity and darkness. In this festival, as in daily observance, the presence of a statue or figurine of a deity is important in making connection and elevating the mind and soul of an adherent.

Diwali is probably the best example of the discipline of Bhakti Yoga which focuses on loving devotion and service. People clean, renovate, decorate, and improve their homes in honor of the goddess of fertility and prosperity Lakshmi, and give thanks for all they have received from her. There are many other deities, however, who may be called upon at Diwali to take the place of Lakshmi depending on what an adherent needs and what has been received over the past year.

The individual deity does not finally matter because all the deities of the pantheon are aspects of Brahman as is the worshipper and the act of worship. The details of the observance do not matter as much as the observance itself which acknowledges one's place in the universe and reasserts one's commitment to recognizing the divine unity in every aspect of one's life and one's connection to others who are traveling the same path toward home.