Imhotep (Greek name, Imouthes, c. 2667-2600 BCE) was an Egyptian polymath (a person expert in many areas of learning) best known as the architect of King Djoser's Step Pyramid at Saqqara. His name means "He Who Comes in Peace" and he is the only Egyptian besides Amenhotep to be fully deified.

In time, he became the god of wisdom and medicine (or, according to some sources, god of science, medicine, and architecture). Imhotep was a priest, vizier to King Djoser (and possibly to the succeeding three kings of the Third Dynasty), a poet, physician, mathematician, astronomer, and architect.

Although his Step Pyramid is considered his greatest achievement, he was also remembered for his medical treatises which regarded disease and injury as naturally occuring instead of punishments sent by gods or inflicted by spirits or curses. He was deified by the Egyptians in c. 525 BCE and was equated with the demi-god of healing Asclepius by the Greeks. His works were still extremely popular and influential during the Roman Empire and the emperors Tiberius and Claudius both had their temples inscribed with praise of the benevolent god Imhotep.

Djoser's Step Pyramid

Under King Djoser's reign (c. 2670 BCE) Imhotep was vizier and chief architect. Throughout his life, he would hold many titles including First After the King of Upper Egypt, Administrator of the Great Palace, Chancellor of the King of Lower Egypt, Hereditary Nobleman, High Priest of Heliopolis, and Sculptor and Maker of Vases Chief. Imhotep was a commoner by birth who advanced to the position of one of the most important and influential men in Egypt through his natural talents.

He may have begun as a temple priest and was a very religious man. He became high priest of Ptah (and was known reverently as "Son of Ptah") under Djoser and, with his understanding of the will of the gods, was in the best position to oversee the construction of the king's eternal home. The early tombs of the kings of Egypt were mastabas, rectangular structures of dried mud bricks constructed over underground chambers where the dead were placed. When Imhotep began building the Step Pyramid he changed the traditional shape of the king's mastaba from a rectangular base to a square one. Why Imhotep decided to change the traditional shape is unknown but it is probable that he had in mind a square-based pyramid from the start.

The early mastaba was built in two stages and, according to Egyptologist Miroslav Verner, "a simple but effective construction method was used. The masonry was laid not vertically but in courses inclined toward the middle of the pyramid, thus significantly increasing its structural stability. The basic material used was limestone blocks, whose form resembled that of large bricks of clay (115-116)." The early mastabas had been decorated with inscriptions and engravings of reeds and Imhotep wanted to continue that tradition. His great, towering mastaba pyramid would have the same delicate touches and resonant symbolism as the more modest tombs which had preceded it and, better yet, these would all be worked in stone instead of dried mud. Historian Mark Van de Mieroop comments on this, writing:

Imhotep reproduced in stone what had been previously built of other materials. The facade of the enclosure wall had the same niches as the tombs of mud brick, the columns resembled bundles of reed and papyrus, and stone cylinders at the lintels of doorways represented rolled-up reed screens. Much experimentation was involved, which is especially clear in the construction of the pyramid in the center of the complex. It had several plans with mastaba forms before it became the first Step Pyramid in history, piling six mastaba-like levels on top of one another...The weight of the enormous mass was a challenge to the builders, who placed the stones at an inward incline in order to prevent the monument breaking up. (56)

When completed, the Step Pyramid rose 204 feet (62 meters) high and was the tallest structure of its time. The surrounding complex included a temple, courtyards, shrines, and living quarters for the priests covering an area of 40 acres (16 hectares) and surrounded by a wall 30 feet (10.5 meters) high. The wall had 13 false doors cut into it with only one true entrance cut in the south-east corner; the entire wall was then ringed by a trench 2,460 feet (750 meters) long and 131 feet (40 meters) wide. Historian Margaret Bunson writes:

Imhotep built the complex as a mortuary shrine for Djoser, but it became a stage and an architectural model for the spiritual ideals of the Egyptian people. The Step Pyramid was not just a single pyramidal tomb but a collection of temples, chapels, pavillions, corridors, storerooms, and halls. Fluted columns emerged from stone according to his plan. Yet he made the walls of the complex conform to those of the palace of the king, according to ancient styles of architecture, thus preserving a link with the past. (123)

Djoser was so impressed by Imhotep's creation that he disregarded the ancient precedent that only the king's name appear on his monuments and had Imhotep's name inscribed as well. When Djoser died, he was placed in the burial chamber beneath the Step Pyramid and Imhotep is thought to have gone on to serve his successors, Sekhemkhet (c. 2650 BCE), Khaba (c. 2640 BCE), and Huni (c. 2630-2613 BCE). Scholars disagree on whether Imhotep served all four kings of the Third Dynasty but evidence suggests he lived a long life and was much sought after for his talents.

Third Dynasty Pyramids

Imhotep may have been involved in the design and construction of the pyramid and complex of Sekhemkhet which archaeologists believe was originally intended to be greater than Djoser's. The pyramid was never completed because Sekhemkhet died in the sixth year of his reign, but the base and first level show similarities in design to Imhotep's work on Djoser's pyramid.

Sekhemkhet was succeeded by Khaba who commissioned his own pyramid, now known as the Layer Pyramid, which was also left unfinished when Khaba died. The Layer Pyramid is also similar in design to Djoser's monument, especially in the square base for the foundation and the technique of building inwards toward the middle of the structure instead of upwards. Whether the Layer Pyramid and Buried Pyramid were designed by Imhotep himself or based on his designs is not known.

There are scholars who argue in favor of Imhotep's personal hand in the later pyramids and others who challenge that claim. As both sides of the debate point to the same evidence, and nothing new has emerged to tip the scales, the matter remains unresolved. Imhotep is thought to have also served the last king, Huni, but as little is known of Huni's reign, this claim remains speculative. Huni was once thought to have built his own pyramids but now those have been positively identified with other kings.

Medical Contributions

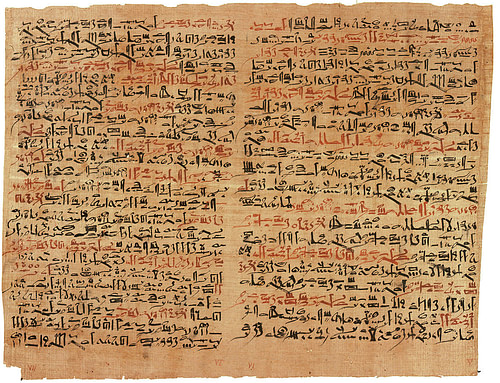

Imhotep was practicing medicine and writing on the subject 2,200 years before Hippocrates, the Father of Modern Medicine, was born. He is generally considered the author of the Edwin Smith Papyrus, an Egyptian medical text, which contains almost 100 anatomical terms and describes 48 injuries and their treatment. The text may have been a military field manual and dates to c. 1600 BCE, long after Imhotep's time, but is thought to be a copy of his earlier work.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is so named for the collector who purchased it from an antiquities dealer in 1862 CE. It is written in hieratic script, the cursive shorthand of Egyptian hieroglyphics. The most interesting aspect of the work is the modern approach it has to treating injuries. Unlike many medical texts of the ancient world, there is little recourse to magical treatments in the Edwin Smith Papyrus. Every injury is described and diagnosed rationally with a following treatment, prognosis, and explanatory notes. This is not to say there is no allusion to medical practices commonly used at the time; the reverse side of the papyrus features eight magic spells and chants for healing.

Examinations are described along the same lines as a modern-day visit to a doctor. Patients are asked where they are injured/feel pain, the physician then addresses the wound by touching or prodding and questioning the patient. The prognosis given after every entry begins with the phrases "An ailment I will handle" or "An ailment I will fight with" or "An ailment for which nothing can be done" which, according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine's article on the subject, "could be seen as the earliest form of medical ethics as an ancient physician would generally refuse to treat a condition he knew was fatal." The National Library article goes on to observe that these prognoses could also have served as a kind of insurance "when a poor outcome is expected" and would have helped save a physician's reputation if treatment failed to cure the patient.

Legacy

A number of didactic writings on morality and religion, as well as poetry, scientific observations, and architectural treatises are also attributed to Imhotep but have not survived; they are referenced in later writers' works. Regarding his masterpiece, the Step Pyramid, Miroslav Verner writes:

Few monuments hold a place in human history as significant as that of the Step Pyramid in Saqqara...It can be said without exaggeration that his pyramid complex constitutes a milestone in the evolution of monumental stone architecture in Egypt and in the world as a whole. Here limestone was first used on a large scale as a construction material, and here the idea of a monumental royal tomb in the form of a pyramid was first realized. In a Nineteenth Dynasty inscription found in South Saqqara, the ancient Egyptians were already describing Djoser as 'the opener of stone', which we can interpret as meaning the inventor of stone architecture. (108-109)

The innovations attributed to Djoser were actually initiated by Imhotep following his vision to build a colossal monument entirely of stone. He was able to imagine a feat never attempted before, perhaps never even conceived of, and make it a reality; in doing so, he changed the world. The great temples and administrative buildings, palaces and tombs, the majestic monuments of the pyramids and towering statuary which came to define the Egyptian landscape, all began with Imhotep's vision of the Step Pyramid at Saqqara.

Once a monument built of stone had been accomplished, it could be attempted again and then again with greater attention to detail and improvement in technology to create the "true pyramids" of Giza. Further, visitors to Egypt who saw these immense creations brought back reports of them to their own countries, such as Greece, who then built upon what Imhotep had first imagined and then made real.