Ionia was a territory in western Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) populated by the Ionians (Greeks who spoke the Ionian dialect) in c. 1150 BCE. It is best known as the birthplace of Greek philosophy (at Miletus) and the site of the Ionian Revolt which prompted the Persian invasion of Greece in 490 and 480 BCE.

The west coast of Anatolia was populated by settlers of the Mycenaean Civilization (c. 1700-1100 BCE) who largely remained near waterways for trade. The interior was part of the empire of the Hittites (1400-1200 BCE) until the Bronze Age Collapse (c. 1250 - c. 1150 BCE), though their reach did not extend to the coastal area which would become Ionia. The kingdom of Phrygia rose in the area after the fall of the Hittites along with Caria, Lydia, and Mysia and these latter three controlled the area from the mouth of the Hermus River in the north to the Maeander in the south which would come to be known as Ionia.

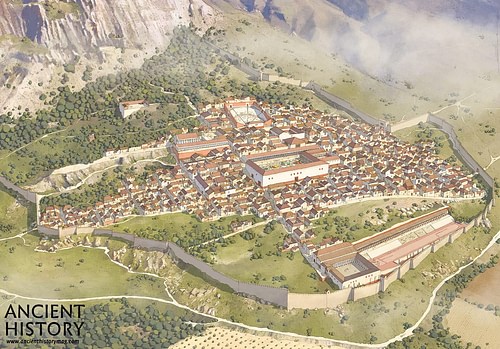

The twelve Ionian cities of the region were:

These 12 formed the Ionian League, a socio-religious pact, in the 7th century BCE and were then joined by Smyrna. The region’s populace was diverse with Aeolian Greeks to the north, Dorian Greeks to the south, and the people of the kingdoms of Mysia, Lydia, and Caria, all of whom interacted through trade and intermarried with the Ionians. Ports of trade, established by the Mycenaeans, drew merchants from Phoenicia and mainland Greece, adding to the mix and, it is thought, providing the fertile intellectual atmosphere that gave rise to the first scientific revolution beginning with Thales of Miletus (l. c. 585 BCE) and developed by the other Pre-Socratic Philosophers.

After Cyrus II (Cyrus the Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE) defeated Croesus of Lydia at the Battle of Thymbra in 547 BCE, the region became part of the Achaemenid Persian Empire and, in 499 BCE, the people rebelled in the Ionian Revolt (499-493 BCE) which was supported by Athens and Eretria. In retaliation, Darius I (Darius the Great, r. 522-486 BCE), launched the first Persian invasion of Greece in 490 BCE which was halted at the Battle of Marathon. His son and successor Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BCE) launched the second invasion in 480 BCE, which was also defeated.

Ionia became part of the empire of Alexander the Great after 335 BCE and was fought over by his generals after his death in 323 BCE, with different regions changing hands with every other military engagement. It was finally controlled mainly by the Seleucid Empire who lost it to Rome in 189 BCE and the Romans placed it under the control of the Attalid Dynasty of Pergamon (also given as Pergamum). The Ionians continued to live in the region throughout the Roman Period and up through the time of the Ottoman Empire (which took control after 1453 CE) up to the present day, contributing to the rich culture of the region.

Name & Early History

According to Herodotus (l.c. 484-425/413 BCE), the Ionians took their name from Ion, the legendary king of Athens, who divided the people into four tribes in establishing social order. They were closely associated with Athens but regarded themselves as Ionians, not Athenians, though Herodotus notes how this claim was essentially meaningless:

It is true that they adhere to the name `Ionian’ more than any other Ionians, so let them have their claim to be pure Ionians. In fact, however, the name applies to everyone who can trace his origin back to Athens. (Book I; 147)

The Ionians were originally from the Peloponnese but, according to Herodotus, Strabo, and Pausanias, were driven out by the Achaeans and fled to Athens where they were given sanctuary. They later migrated to Anatolia, settling in the fertile region of the coast. Herodotus comments on the region and its settlers:

In terms of climate and weather, there is no fairer region in the whole known world than where these Ionians have founded their communities. There is no comparison between Ionia and the lands to the north and south, some of which suffer from the cold and rain, while others are oppressively hot and dry.

They do not all speak exactly the same language, but there are four different dialects. Miletus is the southernmost Ionian community, followed by Myus and Priene; these places are located in Caria and speak the same dialect as one another. Then there are the Ionian communities in Lydia – Ephesus, Colophon, Lebedus, Teos, Clazomenae, and Phocaea – that share a dialect which is quite different from the one spoken in the places I have already mentioned. There are three further Ionian communities, two of which are situated on islands (namely, Samos and Chios), while the other Erythrae, is on the mainland. (Book I; 142)

The Ionian League was formed by these twelve as an expression of common cultural beliefs which were celebrated annually at the Panionic Festival held at the temple known as the Panionium, which was dedicated to Poseidon. The Ionian League was never a political or military alliance but rather a recognition of shared beliefs and history. The Panionic Festival might be compared to a large annual family meeting where participants recognize a common bond but do not necessarily get along or engage socially otherwise.

As noted, the Ionians are understood to have been in the region since c. 1150 BCE but there are no records of their history there until the 8th century BCE when they are mentioned by Homer. They enter the historical record of Anatolia in the Archaic Period (8th century-480 BCE) when, after establishing their cities, they explored the region and some cities, such as Miletus, founded colonies. The Ionian city-states were flourishing in local and long-distance trade by the 7th century BCE when King Gyges of Lydia (r. c. 680-645 BCE) conquered Colophon and Miletus and set the stage for further Lydian incursions.

Lydia & Scientific Revolution

Ionia was conquered completely by Croesus of Lydia (r. 560-546 BCE) whose predecessors had continued Gyges’ policies toward the region. Herodotus notes:

The Ephesians were the first Greeks Croesus attacked, but afterwards he attacked all the Ionian and Aeolian cities one by one. He always gave different reasons for doing so; against some he was able to come up with more serious charges by accusing them of more serious matters, but in other cases he even brought trivial charges. (Book I.26)

Even so, Croesus was no despot and allowed the Ionian city-states significant autonomy. He also contributed to public works in the cities, most famously through his donation to the rebuilding of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus. Ionia continued, at least in spirit, as the independent region it had always been, a kind of re-imagining of a collective past which allowed for greater freedom of thought and expression. This is suggested by their claims regarding the legendary Ion as their ancestor and themselves as “true Ionians” in that, as Herodotus has noted, anyone descended from Athenian stock was an Ionian and there was no historical basis for Ion. The Ionians seem to have created a past and identity for themselves and, this being so, were not as tied to traditional understandings and practices as other peoples.

This, it is thought, gave rise to the scientific revolution that began in the 6th century BCE in Miletus. The term “scientific revolution” in this case should be understood as the advent of critical thinking regarding the creation of the world and how it functioned. At this time, the cosmos was thought to have been created by anthropomorphic gods who interacted daily with humans on earth. If a stream or river flowed in a certain way, it was because the gods had determined that, just as they had the shape of a tree, and their troubles and conflicts created the form of mountains, valleys, and the course of the seasons.

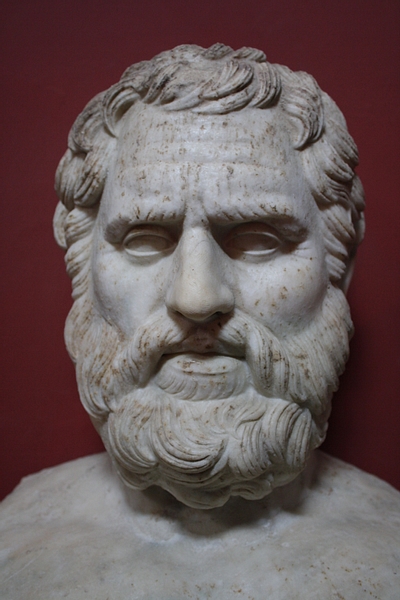

Thales of Miletus claimed that none of these aspects of the known world, necessarily, were the work of the gods but were naturally occurring and, if that were so, their cause could be known. He is the first Greek philosopher to claim that there is a First Cause – the basic “stuff” of the universe – which provides the underlying form for observable, and even invisible, phenomena. He concluded this First Cause was water because it could change form (becoming steam or ice) while remaining essentially unchanged itself. Steam is only rarefied water; ice is water when frozen.

Thales exchanged “the gods” for “energies” and expresses “energy” as “soul” (anima) in that anything that moves must have some “power source” enabling that movement and this energy is naturally occurring, not a supernatural gift from the gods. Thales had studied in Babylon and, according to some scholars, he developed his ideas from those of Babylonian and Egyptian religion while, according to others, he was an original thinker. However he first concluded that the workings of the world could be known through observation and experimentation, he inspired the Pre-Socratic philosophers of Ionia, and elsewhere, to follow his lead.

Persia & the Ionian Revolt

Thales served in the Lydian army as an engineer when Croesus, misinterpreting the message from the Oracle at Delphi to mean he would conquer the Achaemenid Empire, launched the campaign that led to his defeat. Croesus fought Cyrus II to a draw at the Battle of Pteria and then withdrew to demobilize for the winter in 547 BCE, but Cyrus II ignored the traditional rules of war and marched on Croesus at Sardis, the Lydian capital, defeating the Lydian army at the Battle of Thymbra and taking Lydia, including Ionia, as part of his empire. Herodotus describes the Ionian response to the Lydian defeat:

The first thing the Ionians and Aeolians did after the Lydians had been defeated by the Persians was send a delegation to Cyrus at Sardis, since they wanted the terms of their subjection to him to be the same as they had been with Croesus. Cyrus listened to the delegation’s suggestions and then told them a story. A pipe-player once saw some fish in the sea, he said, and played his pipes in the hope that they would come out on to the shore. His hopes came to nothing, so he grabbed a net, cast it over a large number of fish, and hauled them in. When he saw the fish flopping about, he said to them, `It’s no good dancing now, because you weren’t willing to come out dancing when I played my pipes.’ The reason Cyrus told this story to the Ionians and Aeolians was that the Ionians had in fact refused to listen to Cyrus earlier, when he had sent a message asking them to rise up against Croesus, whereas now that the war was over and won, they were ready to do what he wanted…When his message got back to the Ionians in the cities, they all built defensive walls and met in the Panionium – all of them, that is, except the Milesians, who were the only ones whose treaty with Lydia Cyrus renewed. (Book I; 141)

Cyrus offered the Ionian city-states the same, if not more, autonomy than Croesus had but this depended on the policies of the individual satrap (governor) placed over each city. In 499 BCE, Histiaeus (d. 493 BCE), satrap of Miletus, was invited by Darius I to his capital at Susa as a counselor (and to establish his loyalty) and Histiaeus’ son-in-law Aristagoras (d. 496 BCE) became temporary satrap until Histiaeus would return. The same year, a delegation of disenfranchised citizens of Naxos came to Aristagoras asking for military aid in reestablishing themselves and Aristagoras, seeing how this could benefit him, brought the idea to Artaphernes, Darius I’s brother, who then received approval from Darius I.

The campaign was launched with the Persian admiral Megabates (Artaphernes’ cousin) in command of the Persian fleet and Aristagoras commanding Ionians. After a quarrel between the two, Megabates sent word to Naxos of the impending invasion and, when the fleet arrived, the island was well fortified and prepared to withstand a lengthy siege. After months of futile efforts to reduce Naxos, the invasion was called off and Aristagoras, fearing he would be replaced as ruler, chose to revolt against the Persians. According to Herodotus, he was encouraged in this by Histiaeus who was hoping a revolt would return him to power in Miletus.

The Ionians, with support from Athens and Eretria, launched their offensive in 498 BCE, burning Sardis, which had become the capital of the satrapy of the former Kingdom of Lydia. The Persians mounted a counter-offensive, defeating the Greeks at the Battle of Ephesus and continuing to press their advantage until the revolt was put down in 493 BCE. Histiaeus was executed by Artaphernes, and Aristagoras fled to Thrace where he was killed in battle.

Alexander & the Romans

The Persians reestablished control over the region but lost it after their defeat at the Battle of Marathon in 490 after the First Persian Invasion of Greece. Ionia then allied with the Delian League of Athens against the Persians until Athens lost the Second Peloponnesian War in 404 BCE at which time it was under the control of Sparta and then returned to Achaemenid rule. The Ionian city-states fell to Alexander the Great in his conquest of Persia in 335 BCE and, after his death, were contested by his generals in the Wars of the Diadochi (“successors”) until they became part of the Seleucid Empire under Seleucus I Nicator (r. 305-281 BCE).

As with Croesus and the Achaemenids, Ionia retained a degree of autonomy under the Seleucids and the people continued the same traditions and worshipped the same gods as before. When Seleucid authority began to wane, the king Antiochus III (The Great, r. 223-187 BCE) campaigned throughout the empire putting down revolts, including those in Asia Minor (Anatolia). Rome was already a significant power at this time following the Second Punic War (218-202 BCE) and Antiochus III, believing he could stop Roman expansion, met them at the Battle of Magnesia in 190 BCE where he was defeated. The resultant Treaty of Apamea of 188 BCE gave Ionia to Rome who placed it under the control of the Anatolian Attalid Dynasty at Pergamon.

Conclusion

Ionia continued under the Attalids until 129 BCE when Eumenes II, a pretender to the Attalid throne, led a revolt which was quickly crushed and, afterwards, the region was annexed along with the rest of Anatolia as the Roman Province of Asia. Under the Attalids, the Library of Pergamon was established, the most famous intellectual center of the age after the Library at Alexandria, Egypt and, under Roman rule, the Library of Celsus was built at Ephesus between 114-117 CE.

The Library of Celsus, and other monuments and public works built during this period, continued the long-standing tradition of the reigning authority contributing to cultural improvements in the region. In the case of the library, it was commissioned by Tiberius Julius Acquila in honor of his father. This paradigm was followed by others who raised monuments in the region during and after the Roman Period.

The Ionian Greeks outlasted the Western Roman Empire and then the Byzantine Empire, which fell in 1453 CE, and even the Ottoman Empire that controlled the region until 1922. The descendants of the Ionians still live in the same area in the present day and retain the same free spirit of inquiry as their ancestors. Since the ancient Ionian sites were excavated in the late 19th century, they have become a perennial tourist attraction. Ephesus became a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2015 and work continues presently in the region whose history is among the most fascinating in the world.