Jezebel (d. c. 842 BCE) was the Phoenician Princess of Sidon who married Ahab, King of Israel (r. c. 871 - c. 852 BCE) according to the biblical books of I and II Kings, where she is portrayed unfavorably as a conniving harlot who corrupts Israel and flaunts the commandments of God.

Her story is only known through the Bible (though recent archaeological evidence has confirmed her historicity) where she is depicted as the evil antagonist of Elijah, the prophet of the god Yahweh. The contests between Jezebel and Elijah are related as a battle for the religious future of the people of Israel as Jezebel encourages the native Canaanite polytheism and Elijah fights for the monotheistic vision of a single, all-powerful male god.

In the end, Elijah wins this battle as Jezebel is assassinated by her own guards, thrown from a palace window to the street below where she is eaten by dogs. Her death, the biblical authors note, was prophesied earlier by Elijah and is shown to have come to pass precisely according to his words and, so, in accord with the will of Elijah's god.

Her name has become synonymous with the concept of the evil seductress owing to the interpretation of some of her actions (such as putting on make-up in order to, allegedly, seduce her adversary Jehu, who is anointed by Elijah's successor, Elisha, to destroy her) and calling a woman a “jezebel” is to label her as sexually promiscuous and lacking in morals.

Recent scholarship, however, has tried to reverse this association and Jezebel is increasingly recognized as a strong woman who refused to abide by what she saw as the oppressive nature of her husband's religious culture and tried to change it.

Jezebel's Changing Reputation

The story as given in I and II Kings presents Jezebel as an evil influence from the moment of her arrival in Israel who corrupts her husband, the court, and the people by trying to impose her “godless” beliefs on the Chosen People of the one true god. I Kings 16: 30-33 presents King Ahab as a wicked king seduced by the corrupting influence of his new wife and is an audience's introduction to the story:

Ahab, son of Omri, did more evil in the eyes of the Lord than any of those before him. He not only [committed various sins], but he also married Jezebel, daughter of Ethbaal, king of the Sidonians, and began to serve Baal and worship him. He set up an altar for Baal in the temple of Baal that he built in Samaria. Ahab also made an Asherah pole and did more to arouse the anger of the Lord, the God of Israel, than did all the kings of Israel before him.

Traditionally, the story of Jezebel is one of a corrupting influence on a king who had already shown himself a poor representative of his kingdom's religious culture. The biblical account assumes a reader's knowledge that Jezebel, coming from Sidon, would have worshipped the god Baal and his consort Astarte along with many other deities and also assumes one would know that the polytheism of the Sidonians was comparable to that of the Canaanites prior to the rise of Israel and monotheism in their land. Since monotheism and the kingdom of Israel are presented in a positive light, Jezebel, Sidon, and Ahab are cast negatively.

It could be that the biblical narrative depicts events, more or less, accurately but this view is challenged by modern-day scholarship which increasingly leans toward a new interpretation of the clash between Jezebel and Elijah as demonstrating the conflict between polytheism and monotheism in the region during the 9th century BCE. In this interpretation, Jezebel is understood as a princess, the daughter of a king and priest, trying to maintain her cultural heritage in a foreign land against a religion she could not accept. The historian and biblical scholar Janet Howe Gaines comments:

For more than two thousand years, Jezebel has been saddled with a reputation as the bad girl of the Bible, the wickedest of women. This ancient queen has been denounced as a murderer, prostitute and enemy of God, and her name has been adopted for lingerie lines and World War II missiles alike. But just how depraved was Jezebel? In recent years, scholars have tried to reclaim the shadowy female figures whose tales are often only partially told in the Bible. (1)

Although she has been associated with seduction, depravity, and harlotry for centuries, a more accurate understanding of Jezebel emerges as one considers the possibility she was simply a woman who refused to submit to the religious beliefs and practices of her husband and his culture. The recent scholarship, which has led to a better understanding of the civilization of Phoenicia, the role of women, and the struggle of the adherents of the Hebrew god Yahweh for dominance over the older faith of the Canaanites, suggests a different, and more favorable, picture of Jezebel than the traditional understanding of her. The scholarly trend now is to consider the likely possibility she was a woman ahead of her time married into a culture whose religious class saw her as a formidable threat.

Jezebel's Story

Jezebel was married, by contract, to King Ahab of the Kingdom of Israel as a means to cement an alliance between that kingdom and her home state of Sidon. As Gaines notes, there is no way of knowing whether she was pleased with this arrangement and, most likely, she was simply a political pawn:

The Bible does not comment on what the young Jezebel thinks about marrying Ahab and moving to Israel. Her feelings are of no interest to the Deuteronomist [writer], nor are they germane to the story's didactic purpose. (2)

Upon arrival in her new home, she almost immediately comes into conflict with the religious class by importing her own priests and priestesses and setting up shrines and temples to the gods of her own understanding and beliefs. Her seemingly rebellious attitude toward the religion of her husband upsets the prophet Elijah who opposes her from the first. Elijah announces that there will be a great drought on the land, as God is displeased with Ahab and Jezebel's actions, and then exiles himself to the wilderness where he is directed by his god and famously brings the son of the Widow at Zarephath back to life (I Kings 17) but then returns to challenge Ahab and Jezebel to a showdown.

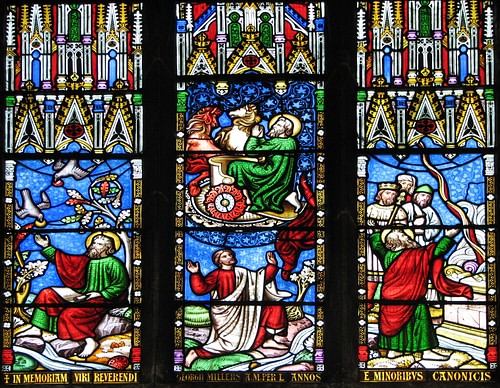

By the time he returns, the drought has become severe and the people are suffering from widespread famine. God tells Elijah to tell Ahab to summon the people to witness a duel between Jezebel's priests of Baal and himself on Mount Carmel. Elijah will call on Yahweh to light a sacrificial bull on fire on an altar and Jezebel's priests will call on Baal; whichever deity is able to light the bull will win the challenge and be acknowledged as the true God. Ahab accepts the challenge and the people, priests of Baal, and Elijah gather at Mount Carmel.

In order to draw the attention of their god, the 850 priests of Baal “performed a hopping dance about the altar” (I Kings 18:26). They also called on his name to hear their petitions and send fire to the altar. All day they danced and prayed and yet no answer came. Elijah, sitting nearby watching them, mocks the priests and asks where their god is. Perhaps, he suggests, Baal is too busy off somewhere eating or having sex or engaging in some other pleasure which prevents him from answering their prayers.

Once they have given up, and Elijah rises for his turn, the writer of I Kings makes it clear which deity is the true one by having Yahweh answer Elijah's prayer immediately:

Fire from the Lord descended and consumed the burnt offering, the wood, the stones and the earth; When they saw this, all the people flung themselves on their faces and cried out: 'The Lord alone is God, the Lord alone is God!' (I Kings 18:38–39).

Elijah has won his challenge and his god is proven to be the only true God, ruler of the heavens and earth. As this god's champion, it is up to Elijah to now impose his god's will on the people of Israel. Gaines writes:

Ironically, at the conclusion of the Carmel episode, Elijah proves capable of the same murderous inclinations that have previously characterized Jezebel, though it is only she that the Deuteronomist criticizes. After winning the Carmel contest, Elijah immediately orders the assembly to capture all of Jezebel's prophets. Elijah emphatically declares: “Seize the prophets of Baal, let not a single one of them get away” (1 Kings 18:40). Elijah leads his 450 prisoners to the Wadi Kishon, where he slaughters them (1 Kings 18:40). Though they will never meet in person, Elijah and Jezebel are engaged in a hard-fought struggle for religious supremacy. Here Elijah reveals that he and Jezebel possess a similar religious fervor, though their loyalties differ greatly. They are also equally determined to eliminate one another's followers, even if it means murdering them. The difference is that the Deuteronomist decries Jezebel's killing of God's servants (at 1 Kings 18:4) but now sanctions Elijah's decision to massacre hundreds of Jezebel's prophets. Indeed, once Elijah kills Jezebel's prophets, God rewards him by sending a much-needed rain, ending a three-year drought in Israel. There is a definite double standard here. Murder seems to be accepted, even venerated, as long as it is done in the name of the right deity. (4)

When Jezebel hears of what Elijah has done, she threatens his life and he flees the land (I Kings 19:1-3). This is hardly the end of their power struggle, however. I Kings 21 relates how Jezebel orchestrates the murder of the landowner Naboth (allegedly using Ahab's signet ring unlawfully to seal the messages sent) in order to give Ahab his vineyards.

Ahab had demanded that Naboth sell him the vineyards since he, Ahab, was king and the vineyards were close to his palace. When Naboth refused, Jezebel had him framed for treason and executed. This is all reported as though Jezebel was duplicitous in her dealings in using Ahab's ring to sign Naboth's death warrant. Recent archaeological discoveries, however, reveal she had her own ring and, accordingly, authority as a monarch to take what actions she deemed necessary (Science Daily, 1). While there is no doubt that the murder of Naboth was unjust, to a queen used to having her own way, it may have seemed simple policy to remove a subject who refused the will of the monarchy.

However that may be, Elijah returns to confront Ahab for the murder and predicts Ahab and Jezebel's deaths, claiming that dogs will lick Ahab's blood from the ground where Naboth's blood was spilled and will “devour Jezebel by the wall of Jezreel” (I Kings 21: 17-23). Ahab hopes to escape this fate by repenting and putting on sackcloth which appeases God who puts off the day of reckoning until the reigns of Ahab's sons.

Elijah had earlier anointed a successor, Elisha, who now anoints the general Jehu as the new king of Israel to destroy the house of Ahab and Jezebel. Ahab has died by this time, killed by wounds sustained in battle, and the narrative notes how the dogs lick his blood from the ground as prophesied by Elijah. Ahab's son Joram succeeds him but is killed by Jehu, as is Joram's nephew, Ahaziah King of Judah.

Jehu then approaches the walls of the city of Jezreel as Jezebel “put on eye makeup, arranged her hair, and looked out of a window” (II Kings 9:30) which has traditionally been interpreted as an effort to seduce Jehu and save herself. If this interpretation is correct, it is difficult to understand why she insults Jehu, calling him a murderer, as he arrives beneath her window.

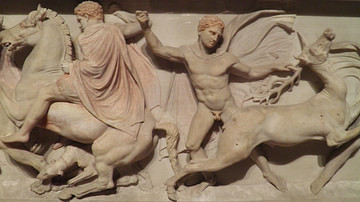

Jehu ignores her insult and rallies those around him to his cause. At Jehu's cry asking who stood with him against Jezebel, “two or three eunuchs looked down at him [from Jezebel's window]. Throw her down!” Jehu said. So they threw her down and some of her blood spattered the wall and the horses as they trampled her underfoot” (II Kings 9:32).

The famous scene from II Kings 9:30 in which Jezebel applies make-up before her death, which has traditionally been interpreted as her attempt to seduce Jehu to spare her life, and has largely led to her reputation as a 'whore', is now believed by some scholars to be the appropriate action of a Princess of Sidon and Queen of Israel, preparing for her end with dignity as a monarch and true priestess of her gods.

After trampling her body under his horses' hooves, Jehu goes into the city to eat and drink and only later gives the command that someone should go and bury Jezebel since “she was a king's daughter” (II Kings 9:34). When the people go to bury her, however, they find nothing except her skull, her feet, and her hands; the rest of her body has been eaten by dogs beneath the walls of Jezreel in accordance with Elijah's prophecy.

Conclusion

The new scholarship, as noted, interprets Jezebel's story in a much more positive light than in previous generations. She has traditionally been seen as a rather one-dimensional villain but, Gaines suggests,

There is more to this complex ruler than the standard interpretation would allow. To attain a more positive assessment of Jezebel's troubled reign and a deeper understanding of her role, we must evaluate the motives of the Biblical authors who condemn the queen. Furthermore, we must reread the narrative from the queen's vantage point. As we piece together the world in which Jezebel lived, a fuller picture of this fascinating woman begins to emerge. The story is not a pretty one, and some—perhaps most—readers will remain disturbed by Jezebel's actions. But her character might not be as dark as we are accustomed to thinking. Her evilness is not always as obvious, undisputed and unrivaled as the Biblical writer wants it to appear. (1)

Phoenician women enjoyed enormous liberty and were considered nearly the equals of males. Both men and women presided over religious gatherings as priests and priestesses and, as daughter of a High Priest, Jezebel would have naturally been initiated into the priesthood. Her ongoing conflict with Elijah has been interpreted by some as simply an impossible clash of cultural understanding as the Israelites were not accustomed to a strong female ruler and Jezebel was not used to being regarded as a second-class citizen.

Her actions may not always have been the most prudent and, sometimes, they were simply evil (as in the case of Naboth) but can be understood as the way in which a Phoenician princess would handle a situation without regard for the cultural norms of her husband's culture. Jezebel clearly rejected the prohibitions against women fully participating in religious rituals and the restrictions placed on them, as described by scholar Monique Alexandre:

At home, women were responsible for dietary and sexual purity but played little religious role in the strict sense. True, they enjoyed the privilege of lighting the sabbath candles and baking the sabbath bread, and it was their task to wash and dress the bodies of the dead and to mourn their passing. But blessings and prayers were reserved for men. (Pantel,417)

Jezebel rejected this kind of life for herself and the women of the kingdom she came to rule over, attempting to replace the patriarchal monotheistic culture she found intolerable with the one she had grown up in. Whether Jezebel is to be considered along these lines or those of her traditional image is naturally up to each individual. A careful examination of the text, however, keeping in mind the narrative focus and purpose of the writers of I and II Kings, may give a reader cause to rethink the popular image of the 'wicked' queen Jezebel and see her, and her infamous name, in a new and better light.