Macedon was an ancient kingdom located in the north of the Greek peninsula first inhabited by the Mackednoi tribe who, according to Herodotus, were the first to call themselves 'Hellenes' (later applied to all Greeks) and who gave the land their name.

The kingdom was founded c. 7th century BCE by Caranus who seems semi-mythical and named after the god Makedon (also given as Makednos, Macedon), a son of Zeus. For centuries, the Mackednoi had little to do with southern Greece and the Greeks considered them barbarians who were useful only for the raw materials their region provided, especially timber for shipbuilding. The Mackednoi, for their part, held the Greeks in equal contempt.

During the Persian invasion of 480 BCE, Macedonia was under Persian rule and compelled to provide troops for the invading force. Their participation on the Persian side does not seem to have worsened the poor relations between Macedonia and southern Greece in any way. Following the Greek victory and expulsion of the Persians, Macedon preferred to remain aloof from the rest of Greece and the squabbles and fighting which constantly took place between the Greek city-states and the southern states did the same with Macedon.

All of this changed under the rule of King Phillip II (r. 359-336 BCE) who systematically brought the southern Greek city-states under his control. After Philip's assassination in 336 BCE his throne passed to his son, Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE), who would spread Greek culture and civilization across the known world of antiquity. Macedon fell out of favor with southern Greece after the death of Alexander in 323 BCE with many Greeks resenting Macedonian rule and virulent antagonism expressed toward anything even remotely Macedonian. Macedon continued as an autonomous and powerful kingdom until it was annexed by Rome, along with the rest of Greece, c.146 BCE.

Early History & Relations with Greece

In the early 7th century BCE the Macedonians, under their king Caranus, settled in the central part of the region and, in time, colonized to the north and south, dislocating the Thessalians and Illyrians who had been living there. Prior to their arrival the land was known as Emathia (according to Homer, 8th century BCE and, later, Strabo, 63 BCE-23 CE) but the new arrivals claimed and named it for their patron god. Makedon is mentioned in Hesiod's Catalogue of Women in the 8th century BCE as belonging to the Greek pantheon. Scholar Winthrop Lindsay Adams writes:

Their foundation legends stated that they were descended from a son of Zeus, Makedon, who in turn had two sons, Pieros and Amathos (these provided a religious history to already existing geographic and ethnic terms). They spoke a dialect called Makednic, vaguely related to Aeolic or to northwest Greek but distinct enough to be practically unintelligible to the Ionic-and-Doric-speaking Greeks to the south. (3)

Language was not the only barrier between the northern region and the south, however, as Herodotus (l. c. 484-425/413 BCE) argues that the Macedonians were Greeks and, at the same time, intimates they were non-Greeks who worshiped Greek gods. Herodotus states that their first king was Perdiccas, a descendent of Temenus who was descended from the Greek hero Heracles (Histories 8:137.1). Although Herodotus links the Macedonians to the Greeks through Heracles, he also makes clear that this was a Macedonian claim, not a Greek one, and only acknowledged by the Greeks in the case of the Macedonian king Alexander I (Histories 5:22). This claim is further complicated in Herodotus by the fact that Alexander was known as the Philhellene (“friend of the Greeks”), an epithet applied to non-Greeks. Scholars generally conclude that, whatever nationality the Macedonians were, they were not regarded as Greek by the southern city-states. Scholar Peter Green comments:

The attitude of the city-state Greeks to this sub-Homeric enclave was one of genial and sophisticated contempt. They regarded Macedonians in general as semi-savages, uncouth of speech and dialect, retrograde in their political institutions, negligible as fighters, and habitual oath-breakers, who dressed in bear pelts and were much given to deep and swinish potations, tempered with bouts of assassination and incest. (6)

Although the Macedonians seem to have kept themselves aloof, there is ample evidence they sought the approval and acceptance of the southern city-states since, as early as Alexander I (r. 498-454 BCE, the first historical king of Macedon) the king presents himself with a Greek pedigree linking him to the Argive kings of the past (illustrious Greek rulers of the city of Argos). Whether Alexander I had such a pedigree is still debated by scholars but his claim was accepted by the Greek authorities who allowed him to participate in the Olympics in c. 504 BCE, an honor reserved only for Greeks. Alexander I further patterned his court after the Athenian model and invited Greek poets there to entertain him.

Even so, the Greeks themselves seem to have consistently regarded Macedonia as a barbaric land which was only worth noting for their considerable resources. Macedonia was divided between the highlands and the lowlands with the upper reaches heavily forested and the lower a flat, fertile plain watered by three rivers. The crops from the lowlands and timber from the highlands became the chief export of the early settlers and would remain so throughout Macedonia's history.

These divisions created small, independent communities which were brought under a single monarchy which originally ruled from the city of Aigai (Vergina) and later from Pella. The king oversaw the administration of the realm as a whole but it was up to individual subordinates to work out details of trade, a policy which seems to have been left over from the time when separate tribes had their own kings. The Macedonians bartered for goods instead of using coinage up until the 5th century BCE and relied heavily on agriculture, especially in the lowlands. Unlike their neighbors to the south, they worked the land themselves and had no slaves; a policy and lifestyle which further encouraged southern Greek contempt.

Early Kings & Culture

The early kings prior to Alexander I are semi-historic and little is known of their reigns. Alexander I's father, Amyntas I (r. 547-498 BCE), is the first Macedonian king on record as entering into treaties and compacts with other nations. It is under the reign of Amyntas I that Macedonia becomes a vassal state of the Persian Empire in c. 511 BCE. Alexander I continued his father's policies and his successor, Perdiccas II (r. 454-413 BCE), expanded on them and exploited every compact he made to gain full advantage. Green writes:

[Perdiccas played] Sparta and Athens off against each other with cool cynicism, selling timber to both sides, making up and tearing up monopoly treaties like so much confetti. He also contrived to keep Macedonia from any serious involvement in the Peloponnesian War, thus preventing that ruinous drainage of manpower which so weakened both main combatants. (8)

Even so, the Macedonia under Perdiccas was still considered a backwards and barbaric land by the Greeks, especially the Athenians, and struggled with problems of disunity and their economy. It was Archelaus (r. 413-399 BCE), Perdiccas' successor, who elevated Macedonia to equal status with the southern city-states. He revitalized and reformed the army, brought the separate cantons of the region more securely under the power of the throne, and instituted a cultural program of increased Hellenization of his court and capital city.

In part, Archelaus' success was due to circumstance: Athens had just lost the Peloponnesian War to Sparta and required massive amounts of timber for new ships. That aside, however, Archelaus was able to see what needed to be done to elevate Macedonia as a whole and the Kingdom of Macedon specifically and set about to do it. He invited some of the most famous Greek poets and artists to his court, Euripides (c. 480-c.406 BCE) among them, and encouraged a high level of culture.

In c. 399 BCE Archelaus was killed on a hunt by one of his companions (and possibly a former lover) named Crateuas who then ruled for four days before being deposed and killed by Archelaus' son Orestes (r. 399-398 BCE) who was then succeeded by Aeropus II (r.c. 398-396 BCE). The next few kings came to the throne and ruled for one or more years before they were assassinated until Amyntas III (r. 392-370 BCE) became king.

Amyntas III secured the country's borders against invasion, increased trade with the Greek city-states, and continued the work begun by Archelaus I in elevating Macedonia's status. He formed alliances with both Sparta and Athens as well as negotiating more lucrative contracts with them for Macedonian timber. Amyntas III is regarded as the true successor to Archelaus I in that he unified and strengthened the country in a way none of Archelaus I's immediate successors could do. He died of old age and left his kingdom to his son, Alexander II (r. 370-368 BCE), who did not live up to his father's vision and none of Alexander II's successors would either. His true successor would be his youngest son Philip II who came to power in 359 BCE and would unify Greece under Macedonian rule.

Philip II

Alexander II was assassinated in 368 BCE and the throne went to Ptolemy of Aloros (r. 368-365 BCE), his assassin, who claimed legitimacy through marriage – or at least an affair – with Amyntas III's widow, Eurydice. The aristocracy of Macedon disapproved of his methods and his overall rule and he was assassinated by Perdiccas III (r. 365-360 BCE) who removed him without anyone's objection. Since c. 367 BCE, Perdiccas III's younger brother Philip had been held hostage first by the Illyrians and then by Thebes, among the most powerful cities in Greece. In Thebes he received a formal education in military and diplomatic matters and witnessed first-hand the effectiveness of the Theban army's military wedge formation as well as the elite fighting force known as the Sacred Band.

Perdiccas III secured Philip's release from Thebes in 364 BCE and he returned to Macedon. Perdiccas III mounted a campaign against the Illyrians to drive them from his northern regions and was killed in battle in late 360 BCE. The throne then went to his son Amyntas IV (r. 359 BCE) who was only an infant and Philip ruled as regent for a short time before deposing his nephew and claiming the throne for himself. He did not regard Amyntas IV as any real threat and treated him well instead of having him killed (Alexander III, however, would later have him executed when he succeeded Philip).

Philip II instantly began a complete overhaul of his kingdom's educational practices and army. He enlarged the armed forces and introduced the tactics and formations he had learned about in Thebes. At the same time, he increased the Hellenization of the region along the lines of Archelaus' policies and brought Aristotle (l. 384-322 BCE) from Greece to tutor his young son Alexander as well as Alexander's companions.

Between 356-348 BCE, Philip II involved himself in the affairs of his southern neighbors by allying with some to conquer others and then conquering those. The Athenian orator Demosthenes (c. 384-322 BCE) delivered a number of speeches (known as the Philippics) against the Macedonian king, warning his fellow citizens of the danger of trusting Philip but these went largely unheeded. In 338 BCE Philip II and Alexander III defeated the combined forces of Athens and Thebes at the Battle of Chaeronea and afterwards formed the Pan-Hellenic Congress with himself as its head. He had effectively conquered the Greek city-states and brought them under Macedonian control.

Macedon was now a powerful and unified kingdom which also accrued wealth through new trade negotiations and tribute from the south. When Philip II was assassinated in 336 BCE – for reasons which were unclear even in antiquity – the throne went to Alexander III who would make the most of the resources he inherited.

Alexander the Great

Philip II had been planning a military campaign against Persia – then the most powerful empire in the world – and Alexander instantly renewed these plans. In 334 BCE he crossed from Greece to Asia Minor with a force of 32,000 infantry and 5,100 cavalry and took the city of Baalbek. In 333 BCE he ably defeated the armies of Darius III at the Battle of Issus but failed to capture him. He took Syria in 332 BCE and Egypt in 331 BCE.

Since he had inherited a strong standing army and full treasury, Alexander had not needed to make any alliances with any other power and was free to do as he pleased whenever he wanted and however he saw fit. Among his goals in conquest, if not his primary goal, was a unification and blending of cultures and so he spread Hellenistic thought, language, and culture wherever he went while also recording the cultures and regions of the lands conquered.

In 331 Alexander defeated Darius at the Battle of Gaugamela and shortly afterwards Darius was assassinated by his own bodyguard. Alexander was now the ruler of all the lands formerly held by Persia but he pressed on in an attempt to conquer India in 327 BCE. Whatever success he may have had in this was cut short when his men threatened mutiny if he did not turn back and he canceled the campaign. He was possibly considering renewing it when he died, after ten days of high fever, in 323 BCE.

Hellenistic Macedon & Rome

Alexander named no successor and so his empire was divided between his four generals, Lysimachus (who would rule Thrace and Asia Minor); Ptolemy I (Egypt, Palestine, Cilicia, Nabatea, Cyprus); Seleucus (Mesopotamia, the Levant, Persia, and India); and Cassander who took Macedonia and Greece. These four were known as the Diadochi (successors) and even though each had enough land and riches to satisfy anyone, they all – with the possible exception of Ptolemy I – wanted more and the Wars of the Diadochi (322-c.275 BCE) began.

These wars involved not only the four generals but others who believed they were due a greater share of Alexander's empire. His half-sister Cynane (c.357-323 BCE), for example, succeeded in marrying her daughter Adea (known as Queen Eurydice) to the man chosen as Alexander's successor – his weak half-brother Arrhidaeus (later known as Philip III, r.323-317 BCE). Alexander's mother, Olympias, also involved herself in the disputes and ultimately had Eurydice and Philip III killed. Alexander the Great's son, Alexander IV, was the most obvious choice as a successor but was born shortly after Alexander's death. He was eventually assassinated under orders from Cassander in c. 309 BCE.

During Alexander's absence, the general Antipater (father of Cassander) ruled Macedonia as regent (334-323 BCE) but proclaimed himself regent of the entire empire in 320 BCE. Cassander, after fighting his various wars against his former comrades, returned to Macedon and believed he would be named successor to his father. Antipater chose his friend and comrade Polyperchon instead and Cassander allied himself with the general Antigonus to gain the throne. Antigonus and Cassander were victorious and in c. 305 BCE Cassander was proclaimed king of Macedon and founded the Antipatrid Dynasty which would last only through the Wars of the Diadochi.

Macedonia's history between c. 275 BCE and c. 205 BCE is characterized by a series of military campaigns by its kings, with varying levels of success, and assassinations of those kings and other members of the aristocracy. The most successful of these kings, at least at first, was Philip V (r. 221-179 BCE) who secured his borders against invading tribes and expanded Macedonian power in Greece and across the Mediterranean through Asia Minor and Egypt.

Macedon became involved in Rome's affairs during the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE) when a Macedonian envoy aboard a ship with a Carthaginian diplomat was captured in 215 BCE and found to be carrying a treaty between Macedon and the Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca. Rome could not afford an alliance between Carthage and Macedon and so the First Macedonian War (214-205 BCE) began. Rome was victorious, as it was also in the Second Punic War, and established itself as the greatest power in the Mediterranean region.

Macedon continued to assert its independence and authority, however, over the next few decades while Rome grew ever more powerful. The Romans had not forgotten or forgiven Philip V for his involvement with Carthage earlier and demanded an exorbitant sum in damages. Philip V refused this demand and so the Second Macedonian War (200-197 BCE) began in which Rome was again victorious and Macedon was forced to surrender its holdings in Greece. The Third Macedonian War (171-168 BCE) and Fourth Macedonian War (150-148 BCE) ended the same way and, each time, Macedon lost a little more. When the Romans won the Third Punic War against Carthage in 146 BCE, Macedonia was soon after absorbed as a Roman province.

Conclusion

Slavic invasions of the region began around the 5th century CE as Rome was falling and continued through the 7th century CE. In 681 CE the First Bulgarian Empire was founded in the region by the Bulgar tribes which would last until 1018 CE when the region was taken by the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantines held it until 1453 CE when they were defeated by the Ottomans who established themselves in the region as part of their empire and who would hold it until the 20th century CE.

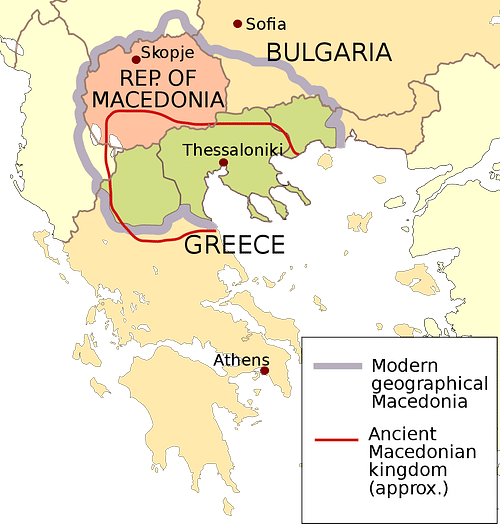

In time, and after much conflict, the region broke into the separate political and ethnic entities which now include Greece, Albania, Bulgaria, Kosovo, Serbia, and Yugoslavia. In 1991 CE the Republic of Macedonia was established in an area of what had once been the Macedonian Empire of Alexander the Great. The legacy of the region was the Hellenization of the ancient world by the armies under Alexander who made the most of what was given him to significantly impact and influence others for generations; a paradigm which exemplifies the people of the land up to the present day.