A martyr is someone who voluntarily dies for either a religious or secular cause. The word originates from "witness" in Greek and is related to a witness in court testifying to one's beliefs or truth, despite the risk involved. As such, it is considered one of the greatest sacrifices that a person can make.

The title and status of martyrdom are assigned by society, where the person/event is memorialized in stories and monuments. Martyrdom is most often juxtaposed to a dominant social or religious worldview or an oppressive government. In the Western tradition, the concept of martyrs and martyrdom is drawn from Greco-Roman stories of a noble death (hero cults), the Jewish Maccabean Revolt of 167 BCE, and the persecution of Christians by Rome.

The Ancient Concept of a Noble Death

The act of voluntary death, suicide, was never condemned in antiquity, but the reason for the death was debated as one that was honorable and necessary. Social memory was an essential concept of the afterlife; without memory, there was no existence. In the philosophical schools, the template for noble death was the story of Socrates (469-399 BCE), as related by his pupil, Plato. Socrates had been put on trial in Athens for corrupting the youth and condemned for execution. Despite plans by his friends, Socrates refused to flee Athens and accepted his fate. His drinking of the hemlock demonstrated that he was in control of his own fate, not the Athenian Greek government.

Ancient Greece had created the concept of hero cults, with apotheosis, or the deifying of individuals after their death. Their accomplishment of great deeds in life was rewarded with being among the gods after death in the Elysian Fields. The god Herakles/Hercules was a model. People made pilgrimages to the sites of the heroes' alleged tombs and were able to petition them for benefits. Rome was slow to borrow this idea, but it became a popular way to honor great generals such as Scipio Africanus, who defeated Hannibal in the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE).

The Maccabean Revolt

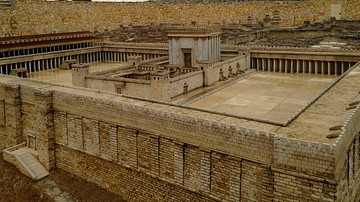

After the death of Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE), Syria was established by the ruling Seleucid Empire. In 167 BCE, Antiochus Epiphanies IV (r. 175-164 BCE) took the unprecedented step in forbidding the Jews to practice their customs. Under the Hasmonean family, the Jews revolted and defeated the Greeks. Known as the Maccabean Revolt, the story is related in four books that are now placed between the testaments in modern Bibles. 2 Maccabees established the template for several innovations that became fundamental to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. We have the story of Hannah, a mother who had to watch her seven sons being tortured and executed for refusing to worship the Greek gods.

The term 'martyr' was introduced for the first time, as a "witness" to why they preferred death. Before each son died, he made a speech, claiming that he was dying for the sins of the nation. The nation must have sinned, or God would not have let the Greeks oppress them; it must be a form of divine discipline. Their deaths are understood as a sacrifice to God as an atonement (a covering over or fixing a violation), and as the vindication of the righteous. They were happy to die for their beliefs, they said, because they knew their God would raise them up (anastasis in Greek, 'resurrection' in English). This is the origin of the reward for martyrdom, both body and soul instantly being taken into the presence of God in heaven.

The Imperial Cult & the Persecution of Christians

After the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE, his heir, Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE), put on his funeral games in Rome. A comet was seen shortly after this, and the common people claimed that Caesar was now among the gods. The Roman Senate gave in to popular demand and officially deified the dead Julius, who could, as such, be worshipped. Temples and priesthood were created for the now deified Julius. Augustus then expanded the idea to the cult of Roma (the personification of Rome), which included the honoring of the imperial family (which now could claim divine ancestors). When Augustus died, he was also deified by the Senate.

At the end of the 1st century CE, Vespasian's (r. 69-79 CE) second son, Domitian (r. 82-96 CE), renewed all the old policies that usually got emperors killed. He quickly went through the treasury and was seeking means to gain income when he remembered the Jewish tax that his father had ordered as reparations for the Great Jewish Revolt of 66 CE. However, apparently, the collection of this Jewish tax had been neglected in Rome and the provinces.

Raiding the tenements in Rome, the Praetorian Guard encountered Christians who claimed that they did not owe a tax because they were not Jews (i.e. they were not circumcised). Ethnic Jews were granted a privilege by Julius Caesar that they did not have to conform to the state cults of Rome, but this new group was confusing. These Christians worshipped the same God as the Jews, honored the Jewish Scriptures, but were not ethnic Jews. Like the Jews, Christians were forbidden to worship the traditional gods of the Roman Empire, and that included the imperial cult. This is most likely the major cause of the beginning of the persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire.

Refusal to participate in the state cults of the Empire was 'atheism', or disbelief in the gods. As the gods were responsible for the prosperity of the Roman Empire, disbelief and nonparticipation were the ancient equivalents of treason. Treason, always and everywhere, resulted in the death penalty. This was the reason that Christians were executed in the arenas, with the phrase, "Christians to the lions." Christians absorbed the story of the Maccabee martyrs; anyone who died for their beliefs was rewarded with instantly being in the presence of God. Early in the Christian tradition, the template was set for believers to act in imitation of Jesus Christ.

Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For whoever wants to save their life b will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me and for the gospel will save it. (Mark 8:34-35).

After Constantine's conversion to Christianity in 312 CE, Christianity became a legal religion, meaning that they had a license to assemble from the Senate. Opportunities for martyrdom were limited. Instead, the new orders of men and women in the movement that became monasticism (3rd-4th centuries CE) became living martyrs. Monastics withdrew from society to devote themselves to prayer and an ascetic lifestyle in the desert. They had sacrificed a normal life (marriage and children) to God.

Like the hero-cults of ancient Greece, Christians now made pilgrimages to the tombs of the earlier Christian martyrs. Understood that they were now in heaven, one could petition the martyr as a mediator, for earthly benefits. Legendary stories of the details of their trials and deaths were constructed as martyrologies, for the benefit of the faithful. This became the cult of the saints by the Middle Ages, an important aspect of the medieval Church.

Judaism

The early rabbis developed criteria for the taking of one's life. Life must be preserved as the commandments were given to live by, not to die by them. Both private and public behavior had to reflect kiddush ha Shem, the "sanctification of the name." It was permissible to violate everyday Jewish rituals to preserve life. There are three exceptions (usually during a time of persecution):

- being forced to murder someone

- sexual misconduct

- idolatry (Tractate Sanhedrin 74a)

Islam

The same concept of martyrdom in Judaism and Christianity was absorbed into Islam by Prophet Muhammad (570-632 CE). Shahid is the term for "witness," but it is also related to the Islamic concept of jihad ("struggle"). The Quran teaches two levels of jihad. The most important is the inner struggle, the daily practice of Islamic concepts and rituals focusing on one's relationship to God. The second jihad is the struggle to defend the faith of Islam. This second jihad has been adopted by radical Islamicist groups who validate the use of violence against others, claiming a defense of their faith.

Islamic martyrs are buried in the clothes they died in and are instantly transported to Paradise (Heaven) where they are given a special place. Islam also accords the status of martyr to those who suffer in this life, such as victims of cancer.

Modern Martyrdom

Modern concepts of martyrdom include what are known as secular martyrs, or people who are willing to die for a social or political cause. Examples of modern martyrs include Abraham Lincoln, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King Jr. Soldiers' funerals are done in accordance with martyrs' funerals, as they gave their lives for God and country. Other world religions have a similar concept, where victims of cultural or government persecution are understood as martyrs.