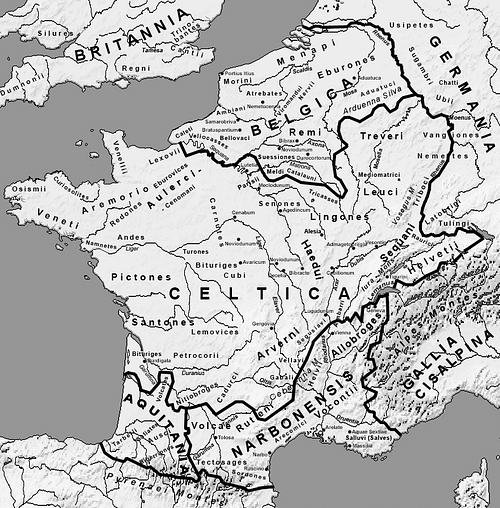

Along the north-western coast of the Mediterranean Sea between Spain and Italy lies the ancient city of Massilia (modern Marseilles). Originally founded in 600 BCE by Ionian Greeks from Phocaea, the city would one day challenge the might of Carthage (defeating them in both the 5th and 6th centuries BCE) and dominate the region, establishing a number of colonies in southern Gaul during the 3rd and 4th centuries BCE. There is also some evidence that sailors from Massilia even travelled beyond the Pillars of Hercules through the Strait of Gibraltar onto the western coast of Africa.

According to most sources, the city was settled on land obtained from the Ligurian Segobriges. Protis, a Greek from Phocaea, had been searching for new trading outposts when he happened upon the cove at Lacydon. This is where history and legend become one. The king of the Segobriges, Nannus, invited the young Greek to a banquet where his daughter, Gyptis, was to choose a spouse among a number of possible suitors. To the surprise of everyone (especially Protis) she deserted the favoured Gauls and presented the ceremonial cup to Protis. Sources vary on whether the cup contained water or wine. As a wedding gift, the king gave the newlyweds land that would become Massilia. The city, located on three hills and overlooking the harbour, would become one of the first ports in Western Europe and a centre of maritime trade. The Greeks would also have a profound effect on the entire region in other ways. According to ancient sources, they taught the locals the “rule of law,” how to cultivate the land, and, most of all, “civility.”

The story of Protis and the founding of Massilia would, however, take a dark twist. After the king's death, his son and heir came to consider the city as a threat and needed to be silenced. The plan was to sneak into the city at night, killing its inhabitants; however, the plot was spoiled when a relative of the king (who had fallen in love with a young Greek) divulged the plan. The participating Ligurians, the young king, and seven thousand of his followers were all killed.

Due to its strategic location, the city would grow rapidly, enjoying a second wave of emigration in 525 BCE after the fall of Phocaea. The presence of Greek culture - especially its architecture and art - at Massilia had a lasting effect from Gaul in the northwest and Spain to the far west; this influence became more evident with the arrival of Greek wine and olives as agricultural products. Although the city remained Greek in nature - complete with a theatre, agora, temples, and docks - its location kept it from participating in any of the Greek wars in the homeland. Instead, they found an ally in their neighbour Rome. While maintaining its independence, the city aided Rome (through the provision of ships) during the Second Punic War against Carthage (218 -202 BCE).

This loyalty to Rome would soon reap benefits. In 125 BCE when the Sulluvii from southern Gaul threatened the safety of Massilia, the city successfully appealed to Rome for assistance. Afterwards, the city served as a link between Gaul and their desire for Roman goods (particularly wine) and Rome's need for resources and slaves. Although the city continued to have ties to the Republic, it was still able to maintain its oligarchic form of government, complete with an assembly of six hundred who elected fifteen magistrates, three of whom had executive power - this independence would, though, soon come to abrupt end.

In 49 BCE the city made the mistake of supporting Pompey in his battle against Julius Caesar. As Caesar marched to Spain, the people of Massilia closed the city gates to him. Leaving three legions to continue an assault upon the city, Caesar continued on to Spain. After a constant barrage with siege towers, siege ramps and battering ram, the city soon surrendered. Although Caesar chose to be merciful, the city still suffered, losing much of its surrounding territory and, most of all, its independence, becoming a member (not by choice) of the Republic.

In the latter stages of the Empire, the city's importance as a commercial centre declined, although maintaining a reputation for Greek culture and learning. Later, with the rise of Christianity, Massilia became a monastic centre and a haven for refugees fleeing barbarians to the north. Like other Roman colonies and cities, it fell to both the Ostrogoths and Visigoths in the mid-fifth century CE, and ultimately to the Franks.