Mycenae was a fortified late Bronze Age city located between two hills on the Argolid plain of the Peloponnese, Greece. The acropolis today dates from between the 14th and 13th century BCE when the Mycenaean civilization was at its peak of power, influence and artistic expression. The archaeological sites of Mycenae and nearby Tiryns are listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

In Mythology

In Greek mythology, the city was founded by Perseus, who gave the site its name either after his sword scabbard (mykes) fell to the ground and was regarded as a good omen or as he found a water spring near a mushroom (mykes). Perseus was the first king of the Perseid dynasty which ended with Eurytheus (instigator of Hercules' famous twelve labours). The succeeding dynasty was the Atreids, whose first king, Atreus, is traditionally believed to have reigned around 1250 BCE. Atreus' son Agamemnon is believed to have been not only king of Mycenae but of all of the Achaean Bronze Age Greeks and leader of their expedition to Troy to recapture Helen. In Homer's account of the Trojan War in the Iliad, Mycenae (or Mykene) is described as a 'well-founded citadel', as 'wide-wayed' and as 'golden Mycenae', the latter supported by the recovery of over 15 kilograms of gold objects recovered from the shaft graves in the acropolis.

Historical Overview

Situated on a rocky hill (40-50 m high) commanding the surrounding plain as far as the sea 15 km away, the site of Mycenae covered 30,000 square metres and has always been known throughout history, although the surprising lack of literary references to the site suggest it may have been at least partially covered. First excavations were begun by the Archaeological Society of Athens in 1841 CE and then famously continued by Heinrich Schliemann in 1876 CE who discovered the magnificent treasures of Grave Circle A. The archaeological excavations have shown that the city has a much older history than the Greek literary tradition described.

Inhabited since Neolithic times, it is not until c. 2100 BCE that the first walls, pottery finds (including imports from the Cycladic islands) and pit and shaft graves with higher quality grave goods appear. These, taken collectively, suggest a greater importance and prosperity in the settlement and Mycenae's role as an important city of an early Greek civilization.

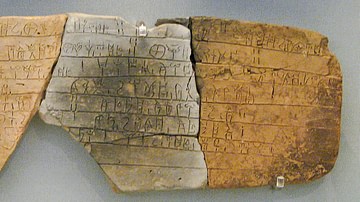

From c. 1600 BCE there is evidence of an elite presence on the acropolis: high-quality pottery, wall paintings, shaft graves and an increase in the surrounding settlement with the construction of large tholos tombs. From the 14th century BCE and the Mycenaean period, the first large-scale palace complex is built (on three artificial terraces), as is the celebrated tholos tomb, the Treasury of Atreus, a monumental circular building with corbelled roof reaching a height of 13.5 m and 14.6 m in diameter and approached by a long walled and unroofed corridor 36 m long and 6m wide. Fortification walls, of large, roughly worked stone blocks, surrounding the acropolis (of which the north wall is still visible today), flood management structures such as dams, roads, Linear B tablets and an increase in pottery imports (fitting well with theories of contemporary Mycenaean expansion in the Aegean) illustrate the culture was at its zenith.

Architecture

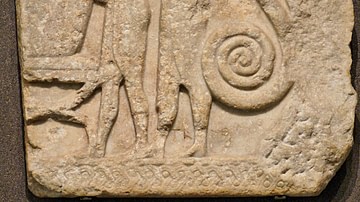

The large palace structure built around a central hall or Megaron is typical of Mycenaean palaces. Other features included a secondary hall, many private rooms and a workshop complex. Decorated stonework and frescoes, city walls and a monumental entrance, the Lion Gate (a 3 m x 3 m square doorway with an 18-ton lintel topped by two 3 m high heraldic lions and a column altar), added to the overall splendour of the complex. The relationship between the palace and the surrounding settlement and between Mycenae and other towns in the Peloponnese is much discussed by scholars. Concrete archaeological evidence is lacking but it seems likely that the palace was a centre of political, religious and commercial power. Certainly, high-value grave goods, administrative tablets, pottery imports and the presence of precious materials deposits such as bronze, gold and ivory would suggest that the palace was, at the very least, the hub of a thriving trade network.

The first palace was destroyed in the late 13th century BCE, probably by an earthquake and then (rather poorly) repaired. A monumental staircase, the North Gate, and a ramp were added to the acropolis and the walls were extended to include the Perseia spring within the fortifications. The spring was named after the city's mythological founder and was reached by an impressive corbelled tunnel (or syrinx) with 86 steps leading down 18m to the water source. It is argued by some scholars that these architectural additions are evidence for a preoccupation with security and possible invasion. This second palace was itself destroyed, this time with signs of fire. Some rebuilding did occur and pottery finds suggest a degree of prosperity returned briefly before another fire ended occupation of the site until a brief revival in Hellenistic times. With the decline of Mycenae, Argos became the dominant power in the region. Reasons for the demise of Mycenae from the 12th century BCE and the Mycenaean civilization in general are much debated with suggestions including natural disaster, over-population, internal social and political unrest or invasion from foreign tribes.

Artefacts

Celebrated artefacts from Mycenae, one of Greece's great archaeological sites, include five magnificent beaten gold burial masks (one being incorrectly attributed to Agamemnon by Schliemann), gold diadems, carved rings, cups and a lion head rhyton. A magnificent bronze and gold rhyton in the form of a bull's head, large bronze swords and daggers with richly inlaid scenes on their blades, ivory sculpture and fragments of fresco also give testimony to the quality of craftsmanship and wealth of 'golden Mycenae'.