Celtic hilltop forts, often called oppida (sing. oppidum), after the Latin name given to larger settlements by the Romans, were built across Europe during the 2nd and 1st century BCE. Surrounded by a fortification wall and sometimes with outer ditches, they were usually located on high points in the landscape or on plains at naturally defensible points like river bends. One of the most famous examples of an oppidum is Alesia, which resisted a siege in 52 BCE by Julius Caesar (l. 100-44 BCE) before its chief Vercingetorix (82-46 BCE) surrendered. Other notable oppida include Gergovia in Gaul, Heidengraben in Germany, and Maiden Castle in Britain. Following the spread of the Roman Empire in the 1st century CE, many oppida were abandoned, but some, like Alesia, remained inhabited into the Middle Ages or retained a religious significance to the local population.

Development & Features

The Celts of Iron Age Europe, thanks to developments in agriculture and manufacturing, were able to prosper and so small urban settlements became more populous. Increasing trade with the Romans and the acquisition of slaves and precious goods resulted in an increase in local rivalries and intertribal warfare as tribes competed for resources. The Celts then built fortifications at easily-defended locations like low hills, mountains, and river bends. There may also have been some religious significance in the choice of a fortified site as attested by multiple votive artefacts found at many of them. They were not necessarily places of permanent occupation, although some were used as such. Rather, many were, in times of war, used as a point of refuge. People had lived in naturally protected spots since the Neolithic period or even earlier, but the Celtic hilltop forts of the 2nd and 1st century BCE were notable for their size and human-made defences. Many oppida spread over an area of several square kilometres (1000 acres). These forts are usually called by archaeologists the Latin name oppida (sing.: oppidum). However, to the Romans, oppidum simply meant ‘settlement’ and could be applied to any area of occupation larger than a mere village.

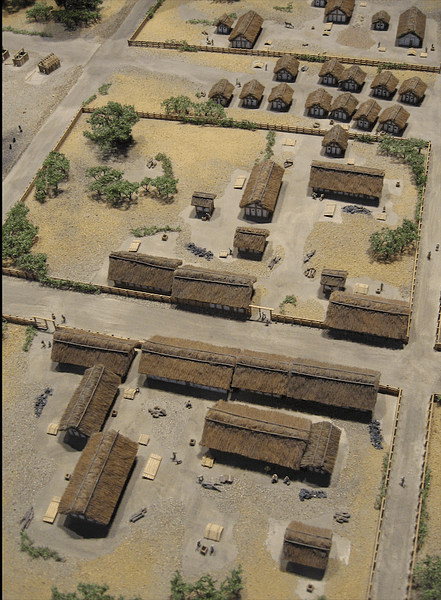

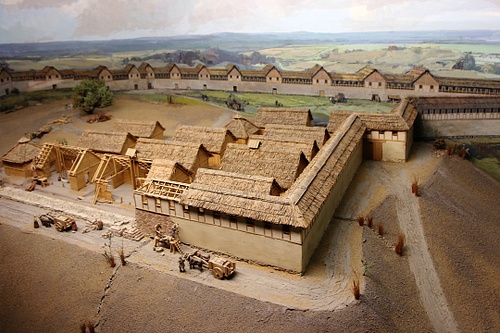

The chosen area for an oppidum was typically encircled by walls with restricted access permitted via gates. The walls, at least at sites west of the Rhine and in southern Germany, were constructed using a technique the Romans called murus gallicus because they first came across it in Gaul. The method was to create a framework of wooden beams attached together using long iron nails. Within the framework, layers of rubble and earth were laid down with more intersecting beams for added strength. The whole was then faced on both sides with cut stone blocks through which the ends of the horizontal beams were still visible. In oppida in Bohemia and Moravia, another method was employed, the post slit wall (Pfostenschlitzmauer or Kelheim wall) where a wall of vertical wooden posts with interconnecting horizontal beams and dry-stone-work was backed by a ramp-like structure of rubble and earth. A third type of defensive wall was prevalent in northern Gaul and southeast Britain. This was the Fécamp type, named after the oppidum of that name. The wall is here made of a mound of earth and rubble with the outer face given a very steep slope and the inner side a gradual one. This type of wall usually had a wide ditch in front for extra protection. All of these structures would have had wooden palisades built on top of them.

The well-built walls created a safe area for the population of the surrounding countryside should the community be attacked. Oppida were also used as secure depositories of precious goods and as manufacturing centres. They were often regional capitals but not always - the Helveti tribe had 12 and the Bituriges had 20 oppida, for example. They did perhaps act as distribution centres of goods, and they collected tribute and tolls since they were frequently located on established trade routes. They may also have been centres of administration and justice. Excavations at oppida have revealed not only workshops for metalworkers and craftworkers like potters, weavers, and glassmakers but also the paraphernalia associated with the manufacture of Celtic coinage. Indeed, the presence of minerals in the vicinity may very well have been an important factor in deciding to build an oppidum in the first place. With the expansion of the Roman Empire, most oppida became obsolete as fortified settlements, but while some were abandoned in the 1st century CE, many did thrive as towns into Late Antiquity.

Oppida in France

Alesia is perhaps the most famous of all oppida. It was a fortified town in eastern Gaul (today’s Burgundy region) and the main hillfort of the Mandubii tribe. The 1st-century BCE Greek writer Diodorus Siculus noted the legend that Alesia was founded by Hercules following his romantic involvement with Galata, the Gaulish princess. Alesia was located between two rivers, on a natural limestone plateau significantly higher than the surrounding plain. It covered around 1 square kilometre (240 acres) and was protected by an encircling wall and surrounding ditch. Alessia was noted in antiquity for its metalwork industry, a reputation confirmed by the archaeological record.

Alesia rose to historical fame when it became the centre of resistance to the invasion of Gaul by Julius Caesar in 52 BCE. The Gaulish chiefs were led by Vercingetorix who enjoyed some success against the Romans. However, a protracted siege and Caesar’s building of his own fortifications to entirely encircle the site ended in Vercingetorix’s surrender (or betrayal by rival chiefs), and Alesia fell to the Romans. The Romans then occupied the oppidum, and it remained a settlement of note into the Middle Ages; there is still a small village on the site today, Alise-Sainte-Reine.

Another famous Gaulish oppidum was Gergovia in southeast France (although absolutely certain identification is yet to be achieved). It was the capital of the Arverni and the hometown of Vercingetorix. Built on a remote high plateau, the fortified site covered around 750 square metres (0.18 acres). In contrast to the fate of Alesia, Julius Caesar's blockade of well-fortified Gergovia, also in 52 BCE, was a rare failure after the Romans were betrayed by their Gaulish allies.

Bibracte was an oppidum in eastern central France located on Mt. Beuvray at a height of around 760 metres (2,500 ft). Bibracte was once the capital of the Aedui tribe, and it was the place where Vercingetorix was given command of all the Gaulish tribes by a great assembly of chiefs. The main site covered around 1,3 square kilometres (320 acres) while an outer ring of ramparts enclosed a total area of 2 square kilometres (500 acres). Archaeological excavations at the site have revealed thousands of artefacts related to Celtic domestic life, and these have made an important contribution to our understanding of pre-Roman Gaul. The huge number of Roman amphorae, for example, show that there was a thriving wine trade in the region long before Julius Caesar’s arrival. The excavations have also shown that the oppidum was divided into distinct areas for religious purposes, the elite, and artisans. Archaeologists have discovered three votive inscriptions mentioning the goddess Bibracte whom the site was named after. Bibracte was another oppidum which remained occupied well into the Roman period, starting with Julius Caesar himself who wrote his Gallic Wars while staying the winter there.

Oppida in Germany

The fortified hilltop settlement at Heuneburg on the west bank of the Danube in southeast Germany is unusual in that it was fortified much earlier than other sites. In the 6th century BCE the site was given a 600-metre (1968 ft) long mud-brick wall set upon a stone base and punctuated with square towers. The wall is 4 metres (13 ft) high in places. The stone needed for this large-scale project was quarried from a source of limestone 6.5 kilometres (4 miles) away. Evidence of archaeological finds and building techniques strongly suggest contact had been established with the Etruscans. Spread around the fortified area are 11 tumuli.

Heidengraben (a modern name) is a Celtic hilltop fort in southern Germany. The largest known oppidum, its walls once enclosed some 16.5 square kilometres (4,100 acres), although a large part of the settlement was naturally protected by the rivers Danube and Rhine. One area of the oppidum, likely the nucleus of the settlement, was given extra protection with a rampart and pits.

Manching was another large oppidum, this time in Bavaria and located near to significant deposits of iron. Covering an area of around 3.8 square kilometres (940 acres), its impressive wall was some 7-8 kilometres (4-5 miles) in length and reached a height of over 4.5 metres (15 ft). An interesting feature of its walls is that they were first built using the murus gallicus technique and then using the Kelheim type. The site had several main roadways, a dense central area of occupation, and an area likely used to pasture livestock. Archaeological excavations have revealed many interesting artefacts, including a bronze and gilded branch with leaves, perhaps once part of a sacred tree.

Oppida in the Czech Republic

Staré Hradisko is located in Moravia in the east of the Czech Republic. Covering some 400,000 square metres (100 acres), the site was enclosed within a series of fortifications whose total length was around 3.2 kilometres (2 miles). The prosperity of the site was based on its proximity to established trade routes, especially of amber.

Závist is another Czech oppidum, this time located south of Prague on a steep hill where the rivers Beraun and Vltava meet. The main fortified site dates to the 2nd century BCE, but there was within it a much older sanctuary, perhaps dating to the 6th century BCE. Závist once covered some 1.7 square kilometres (420 acres) and had fortification walls some 9 kilometres (5.5 miles) in total length. Závist experienced several attacks over time as the walls and main gate show evidence of being repeatedly rebuilt. In the 1st century BCE, new fortified areas were added to the site indicating a growth in its population. The site was destroyed by a fire and abandoned towards the end of the 1st century BCE.

Oppida in Britain

As the Celts moved northwards, so they brought the idea of the oppidum to southern Britain. Ancient Britain did already have hilltop forts but these were different from most oppida on the continent as they did not generally include domestic architecture, i.e.: they were only used in times of war and for temporary occupation. The Celtic oppida were, therefore, projects built on a much grander scale.

Yarnbury Castle in Wiltshire was constructed as a hillfort in the 1st century BCE on the site of an older fortification. More or less circular in form, its double ramparts were separated by a ditch and the primary gate was protected with its own triangular fortification structure (a ravelin).

Maiden Castle in Dorset, southern England, is the largest Iron Age hillfort in Britain. It has been well-studied by archaeologists and provides an interesting insight into how hillforts were continuously improved upon over time. First a Neolithic site, then a fortified settlement from the 5th century BCE, the site went into decline and was then rebuilt and extended c. 400 BCE. This new site covered around 180,000 square metres (46 acres). The Celtic stage in the fort’s history began around 250 BCE and saw another round of building. The inner rampart was raised and extended while the outer earth slopes were also improved and the gates designed to restrict the number of enemy warriors who could access it at any one time. In the 1st century BCE, the ramparts were again extended and the gates reinforced using stone elements and a complex series of outer walls. Outer ditches and stakes offered extra protection to what was by now a formidable fortress by Iron Age standards. Traces of roundhouses and storage buildings suggest the population of the fort was fewer than 1,000 at its peak and dependent on the surrounding agrarian communities, making it what archaeologists term a proto-urban site, rather than a town proper. Finds of substantial caches of stones for slings remind of the site’s primary function as a place to conduct defensive warfare.

Unfortunately for the locals, the defences at Maiden Castle were no match for the Roman army and the sophisticated weapons of Roman siege warfare. The fort was captured in 43 CE, likely by legions commanded by the future Roman Emperor Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE). The site was definitively abandoned a few decades later, its place in the region - the fate of so many Celtic hilltop forts - was usurped by a new Roman town, in this case, Durnovaria (Dorchester).