Phrygia was the name of an ancient Anatolian kingdom (12th-7th century BCE) and, following its demise, the term was then applied to the general geographical area it once covered in the western plateau of Asia Minor. With its capital at Gordium and a culture which curiously mixed Anatolian, Greek, and Near Eastern elements, one of the kingdom's most famous figures is the legendary King Midas, he who acquired the ability to turn all that he touched to gold, even his food. Following the collapse of the kingdom after attacks by the Cimmerians in the 7th century BCE, the region came under Lydian, Persian, Seleucid, and then Roman control.

Historical Overview

The fertile plain of the western side of Anatolia attracted settlers from an early period, at least the early Bronze Age, and then saw the formation of the Hittite state (1700-1200 BCE). The first Greek reference to Phrygia appears in the 5th-century BCE Histories of Herodotus (7.73). The Greeks applied the name to the Balkan immigrants who, sometime after the 12th century BCE, relocated to western Anatolia following the fall of the Hittite Empire in that region. The kingdom's traditional founder and first king was Gordios (aka Gordias). A legendary figure, Gordios is most famous today as the creator of the 'Gordian Knot', a fiendishly difficult piece of rope-work the king had used to tether his cart. The story goes that an oracle had foretold that the person who knew how to untie the knot would rule over all of Asia, even the whole world. The cart and the knot were, incredibly, still there at Gordium when Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) arrived a good few centuries later. Alexander was said to have heard the story and, rather unsportingly, sliced the knot open with a single blow of his sword. In other accounts, the young general slipped the pin out of the cart's yoke pole and slid the knot off that way.

The neighbouring states of Phrygia, which similarly formed out of the remnants of the Hittite Empire, were Caria (south), Lydia (west), and Mysia (north). Phrygia's territory expanded to reach Daskyleon in the north and the western edge of Cappadocia. Phrygia prospered thanks to the fertile land, its location between the Persian and Greek worlds, and the skills of the state's metalworkers and potters. Chamber tombs, especially at the capital Gordium, have distinctive doorways and their excavated contents have revealed both the use of the language of Indo-European Phrygian (from the 8th century BCE) and the wealth which gave rise to the legend of the fabulously rich King Midas (see below).

Phrygia was conquered by the Cimmerians in the 7th century BCE but the period of domination by Lydia and Persia has left an impoverished archaeological record. We know that Lydia expanded under the reign of the Mermnad dynasty (c. 700-546 BCE), and especially King Gyges (r. c. 680-645 BCE). Phrygia was absorbed c. 625 BCE with Gordium conquered around 600 BCE. Lydia then continued to prosper with such famed kings as Croesus (r. 560-547 BCE). Over the next century, the Persians took over Anatolia following the victory of Cyrus II (d. 530 BCE) over the Lydians at the Battle of Halys in 546 BCE. The region was then made a Persian satrapy. Phrygia continued to be used as a label of convenience for the general and ill-defined geographical area which had once been ruled by the now-defunct kingdom of that name.

After the campaigns of Alexander the Great, the region of Phrygia/Lydia came under the control of one of Alexander's successors, Antigonus I (382-301 BCE). Shortly after, Anatolia became a part of the Seleucid Empire c. 280 BCE. As a consequence of this takeover, many settlers came from ancient Macedon and their Hellenistic culture with them. Notable Phrygian towns in this period besides Gordium included Hierapolis, Laodikeia by the Lykos (aka Laodicea), Aizanoi, Apamea, and Synnada, although most of the region's population lived in small, agriculturally-based villages.

Phrygia became a part of the Roman province of Asia (with a part in Galatia, too) in 116 BCE, and the region now grew in scope, at least as a geographical term. To quote the Oxford Classical Dictionary:

During the Roman period the region extended north to Bithynia, west to the upper valley of the Hermus and to Lydia, south to Psidia and to Lycaonia, and east as far as the Salt Lake (1142).

Phrygia then became embroiled in the Mithridatic Wars of the 1st century BCE between Rome and the kings of Pontus. With the reign of Augustus (27 BCE - 14 CE), there followed a period of peace and stability in the region. Prosperity was ensured by the continued fertility of the land and the important marble quarries near Dokimeion - stone from there would be used in such buildings as Trajan's Forum in Rome and the Library of Celsus at Ephesus. Into the 3rd century CE, the culture of the region had become a mix of indigenous Anatolian, Greek, Roman, Jewish, and Christian practices and customs. The Phrygian language, as attested by inscriptions, was still in use in the 3rd century CE, although it is called New Phrygian by historians to distinguish it from the Old Phrygian used when the kingdom itself was in existence (the link between the two was likely created by the language being spoken only as a vernacular in the interim).

King Midas

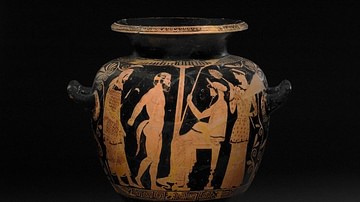

Perhaps the most famous figure from Phrygia's long history is Midas, the king who reputedly could turn anything he wished into gold. The familiar figure from Greek mythology may have been based on an actual late-8th century BCE ruler known in Old Phrygian inscriptions and Assyrian sources as 'Mita of Mushki' (r. 738 BCE - c. 696 BCE). According to the legend, Midas had helped the satyr Silenus recover from the morning-after effects of a night of overdrinking and restored him to his master, the god of wine Dionysos. In gratitude, the god granted Midas a single wish and so the king gained his ability to turn anything he touched into gold. Rather too good to be true, this skill proved a bit of a problem when Midas wanted to eat or drink as even these things changed into the precious metal. Asking Dionysos to withdraw his wish, Midas was told he could lose the bothersome ability if he washed in the river Pactolus in Lydia (a river, not coincidentally, famous for its gold dust deposits).

Midas might have been a wealthy mortal but he seems to have been unlucky with the gods twice. In another unfortunate encounter, this time with Apollo, the king offended the deity when he was asked to judge who was the better musician, Pan or Apollo. Midas unwisely chose Pan, and a displeased Apollo turned the king's obviously tone-deaf ears to those of a donkey. The king was obliged to wear a turban for the rest of his days.

Gordium

Although generally speaking Phrygia did not boast the large cities seen on the western coast of Anatolian such as Pergamon and Ephesus, there were one or two important urban areas, notably, of course, the capital of the kingdom Gordium. Also known as Gordion, the city was strategically located at the point where the main land route to the east coast - often called the Persian 'Royal Road' - crossed the ancient Sangarios River (modern name Sakarya River and about 100 km or 62 miles west of Ankara). The settlement likely became the most important one in the Phrygian kingdom from the 10th century BCE. At its peak during the 9th century BCE (according to carbon-dating techniques), the city now boasted a fine royal palace, impressive fortification walls, and has provided archaeologists with many tumuli tombs, including possibly the one of Midas/Mita. The latter tomb, given the rather unromantic name of 'Tumulus MM' by scholars, is the second-largest ancient tumulus in Anatolia.

Gordium was sacked by the Cimmerians during their invasion of the region but did recover, albeit never really regaining anything like its former glory. The Romans destroyed the town during their campaign against the Galatians in 189 BCE, and by the 1st century CE, it was nothing more than a village.

Religion

The religion of Phrygia, like the culture in general of the region, was a mix of Greek, Anatolian, and Near Eastern elements. Inscriptions have revealed some details such as the predominance of Zeus, Apollo, the Anatolian god Men, a couple of deities referred to only as 'Holy and Just' in texts, and several mother goddesses. Cults were dedicated to these gods and the ideals of justice, righteousness, and vengeance seem to have been particularly important. From the 3rd century CE, Christianity was particularly popular in the region, and this may have been due to its moral code being similar to the indigenous beliefs which dated back to prehistory. Impressive remains which can be visited today include the well-preserved Temple of Zeus at Aizanoi (92 CE), the Roman theatre at Hierapolis (2nd century CE), and the Temple A at Laodicea (2nd century CE).