Titus Maccius Plautus, better known simply as Plautus (actually a nickname meaning 'flatfoot'), was, between c. 205 and 184 BCE, a Roman writer of comedy plays, specifically the fabulae palliatae, which had a Greek-themed storyline. His plays are the earliest complete surviving works from Latin theatre and they are noted for adding even more outrageous comedy to traditional comic plays. Plautus is also celebrated as a developer of characterisation and a master of verbal acrobatics. Finally, the plays are a rich and valuable source of information regarding contemporary Roman society.

Biographical Details

Details of Plautus' life are sketchy and unreliable; even his name may be simply a collection of nicknames attributed to a particular playwright. Plautus is said to have been born in Sarsina, Umbria. Ancient sources, now largely discredited as pure invention, tell of his early career in theatre when he worked as a stagehand, his bankruptcy from spurious business ventures, and his time working in a mill to make ends meet.

Plautus' Complete Works

Twenty complete plays by Plautus survive along with around 100 lines of Vidularia (The Suitcase) and fragments from several others. This body of work was first attributed to Plautus by the 1st century BCE Roman scholar Varro and the titles are:

Early works:

- Cistellaria (The Casket Comedy)

- Miles Gloriosus (The Swaggering Soldier)

- Stichus (200 BCE)

- Pseudolus (191 BCE)

Later works:

- Bacchides (The Bacchis Sisters)

- Casina

- Persa (The Persian)

- Trinummus (Threepence)

- Truculentus (The Ferocious Fellow)

Date/period unknown:

- Amphitruo

- Asinaria (The Comedy of Asses)

- Aulularia (The Pot of Gold)

- Captivi (The Prisoners)

- Curculio (The Weevil)

- Epidicus

- Menaechmi (The Menaechmus Brothers)

- Mercator (The Businessman)

- Mostellaria (The Haunted House)

- Poenulus (The Punic Chappie)

- Rudens (The Rope)

Influences & Style

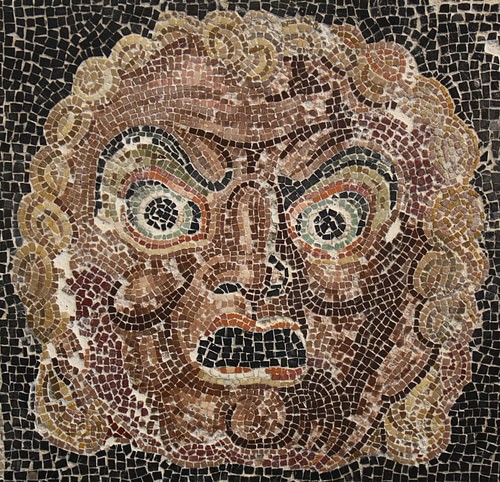

These works are adaptations of 4th century BCE Greek New Comedy (and perhaps also Middle Comedy) plays with some Latin Comedy additions such as mime and bawdy jokes. The earlier Greek plays already had stock characters and Plautus freely expanded the roles of such staple characters as the cunning slave, the cook, and the parasite, giving them memorable character names into the bargain – for example, Chrysalus (Goldfinger) from Bacchides.

The plots of Plautus' plays are also stretched to implausibility so as to heighten their comedy. Confusions of identity and misunderstandings between characters are frequently employed for comedic purposes. Many plays are set in a world which is reversed from the norm, as in the Roman Saturnalia festival where, for a brief time, slaves became masters and vice-versa. Hence, in Plautus' plays, very often, the cunning slave character comes to the aid of a young lover and both get the better of the old master. In addition, the plays often have an ambiguous morality where lovers are unsuitably matched and such characters as prostitutes are not negatively portrayed.

Plautus employs a full range of language from colloquial phrases to technical terms and he frequently uses wordplay, alliteration and puns to deliver a series of devastating linguistical acrobatics. The plays have a great variety of both metre and music too, especially in the cantica segments – operatic arias and duets. Plautus also frequently reminds the audience that they are watching a play (metatheatre) to squeeze even more comedy from his scenes, using such tricks as signalling to the audience exactly how the play is progressing and reminding them that the story is set far away in Greece.

Plautus' Legacy

Plautus' plays continued to be popular after his death and they were performed in Rome for another century or so. His works were also read, studied, and copied for centuries after that. The oldest manuscript of a Plautus play dates back to the 6th century CE and the reappearance of previously lost manuscripts made Plautus once more popular during the Renaissance. The plays were performed in theatres again and, along with Terence, Plautus is credited with influencing the evolution of European comic theatre and inspiring such playwrights as Shakespeare and Molière with his rich characterisations. For example, the former writer's Comedy of Errors shares many plot and character details with Plautus' Menaechmi.

Below is a selection of extracts from Plautus' plays:

Peniculus: Gods confound who first invented public meetings, that device for wasting the time of people who have no time to waste. There ought to be a corps of idle men enrolled for that sort of business. (The Menaechmus Brothers, lines 420-472)

Pseudolus: The best laid plans of a hundred skilled men can be knocked sideways by one single goddess, the Lady Luck. It's a fact; it's only being on good terms with Dame Fortune that makes a man successful and gives him the reputation of being a clever fellow. (Pseudolus, lines 641-693)

Euclio: The first thing that occurs to me, Megadorus, is that you are a rich man, a man of influence, and I'm a poor man, poorest of the poor. And the second thing that occurs to me is that for me to make you my son-in-law would be like yoking an ox with an ass; you'd be the ox and I'd be the ass. Unable to pull my share of the load, I, the ass, would be left sprawling in the mud, and you, the ox, would take no more notice of me than if I had never been born. I should be out of your class, and my class would disown me; if there were a question of divorce or anything like that, my footing in either stable would be very – unstable. The asses would be at me with their teeth, and the bulls with their horns. It's asking for trouble for an ass to promote himself to the bull-pen. (The Pot of Gold, lines 213-256)

Playwrights no longer use the pen

To improve the minds of decent men.

If we have pleased, not wearied you,

If you think virtue worth reward,

Kind friends, you all know what to do…

Just let us know it – and applaud.

(The Prisoners, epilogue)