The Quran (also written Qur’an or Koran), revealed in the 7th century, is the sacred book of Islam, following in the tradition of the Abrahamic faiths, with the Torah as the sacred book of Judaism and the New Testament as the sacred book of Christianity.

Tarif Khalidi, a Palestinian historian who was formerly Sir Thomas Adams’ Professor of Arabic at Cambridge University and currently holds the Shaykh Zayed Chair for Arabic and Islamic Studies at the American University of Beirut says:

The Qur’an is the axial text of a major religious civilization and a major world language. For both Islamic civilization and the Arabic language the Qur’an consecrates a finality of authority granted to few texts in history.

(Khalidi, ix)

The Revelation

For the Muslim faithful, the Qur’an contains the verses of the word of God as revealed in the Arabic language to the Prophet Muhammad (also written Muhammed, c. 570 – 632) over the course of 22 years from approximately 610 to 632. The word qur'an derives from the Arabic verb qara'a meaning to read or recite. The very first Sura (chapter) revealed to the Prophet Muhammad while he was on a spiritual retreat in a cave was:

In the name of God,

Merciful to all,

Compassionate to each!

Recite, in the name of your Lord!

He Who Created!

He created man [humankind] from a blood clot.

Recite! Your Lord is most bountiful.

He taught with the pen.

He taught man [humankind] what he knew not.

Sura 96 The Blood Clot, Aya (Verses) 1-5 (Khalidi trans, 515)

Key texts within the tradition of Islamic heritage, the sayings, hadith (reports), and stories that form the sunna, a record of the Prophet’s life, recount the occasion of the revelation of the Qur’an to the Prophet on the Night of Power, Laylat al-Qadr – generally attributed to the 23rd or 27th night of the month of Ramadan – sacred to Muslims. In the year 610, at 40 years of age, Muhammad sat in meditation in the cave of Mount Hira and was approached by the angel Gabriel who ordered him: Recite! Muhammad was unable to speak until the third time he was commanded and then recited the sura (chapter) 96 above. Unsettled by this encounter, Muhammad set out in search of his wife Khadija who wrapped him in a cloak to stop him from shivering.

However, he then received the revelation of Surah 74, telling him to stand up and preach his message:

In the name of God,

Merciful to all,

Compassionate to each!

You who are enfolded in your garments:

Stand up and warn!

Magnify your Lord!

Purify your garments!

And abandon impurity!

And give not hoping to get more! Be steadfast to your Lord!

Sura (Chapter) 74 Enfolded, Aya (Verses) 1-7 (Khalidi trans, 486)

Assembling the Qur’an

During the Prophet’s lifetime efforts were made by many of his close companions, his cousin Ali ibn Abu Talib chief among them, to write down the verses that he had recited. However the literary culture of Meccan society during the 7th century was an oral rather than a written one, and accordingly, the transmission of verses of the Qur’an among the nascent Muslim community (Umma) was by recitation and spoken word. Approximately 18 years after the death of the Prophet Muhammad in around the year 650 the verses of the Qur’an were collected and assembled into the book’s current form by the third Muslim caliph, Uthman ibn Affan (c. 573-656).

The death of the Prophet Muhammad was followed immediately by a schism regarding the rightly appointed inheritor of the Prophet’s authority. For Sunni Muslims, who make up the majority of the Muslim world today, this was Abu Bakr (c. 570–674) one of the early converts to Islam and a close companion of the Prophet. For Shia Muslims, Ali ibn Abu Talib, a cousin of the Prophet and also husband to his daughter Fatima — his only surviving child by his first wife Khadija, and father of his grandchildren by her. Ali was also the first person after Khadija to accept Islam and recognise Muhammed’s prophethood.

After the Prophet’s death, Abu Bakr made immediate efforts to write down the verses of the Qur’an. According to Shia historians Ali – the first Shia Imam or inheritor of the Prophet’s authority, and the fourth Sunni Caliph or religio-political emperor of the Muslim community, was one of the earliest scribes to have recorded the verses of the Qur’an and collected them into a codex known as the Mushaf of Ali. The Mushaf assembled the Qur’anic revelations, organising them chronologically according to the dates of revelation.

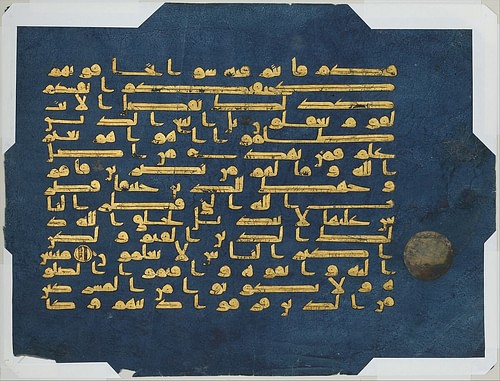

However, Ali’s codex was rejected by the Caliph Uthman, reportedly for political reasons due to the strife between the early Sunni and Shia communities. Instead, Uthman compiled the Qur’an arranging the verses following the Fatiha or Opening by chapter length, longest to shortest, resulting in the Qur’an we have today. The Qur'an was the first book written in the Arabic language, which has 28 letters. This alphabet is written using 18 rasm (shapes) that are then further distinguished by i'jam (dots above and below) and by harakat (short vowels) also applied above and below the rasm. The early written texts of Qur'anic verses used a slanting script called hijaz that predates the later more angular and geometric kufi script. Often the i'jam and harakat were missing from these texts which served more as a memory aide for reciters already familiar with the verses, than as a written record of the Qur'an. Uthman's Qur'an was among the first to incorporate i'jam and harakat, assembling a book that someone who had never heard the oral recitations of the verses could read.

Professor Azim Nanji says in The Penguin Dictionary of Islam,

…it was important to establish a fixed written version in order to avoid the risk of violating the sacred text and to prevent differences arising regarding its contents. On the basis of the previous systemisation and arrangement, a written text was compiled and copies sent to all areas of the growing Muslim world. For Muslims, therefore, the Quranic text has existed unchanged for fourteen centuries and is believed to contain the complete message revealed to the Prophet.

(Nanji, 150)

The Qur’an as we know it today has 114 suras or chapters. The number of verses varies greatly between the suras. The suras are also catalogued as having been revealed to the Prophet while he was in either Mecca 610-622, or Medina 622-632. Therefore, some chronological information is still maintained. Each chapter with the exception of chapter 9 begins with the basmala:

In the name of God,

Merciful to all,

Compassionate to each!

(Khalidi, 3)

“The Word of God”

Meccan society during the time of the Prophet Muhammad was a society of poet-kings. Often the tribe that would rule Mecca and control its lucrative trade routes was decided by a poetry contest. However, much of the population of Arabia was illiterate, therefore the literary culture was an oral one. In keeping with the Abrahamic tradition of identifying its prophets by identifying them with miracles — for Moses the parting of the Red Sea, for Jesus his virgin birth and resurrection — Mohammed’s miracle was that of an allegedly illiterate man standing in the streets of Mecca reciting poetry that far surpassed anything the Meccans had heard before. It stopped them in their tracks and forced them to listen to a man whom they would otherwise ridicule.

Muhammad Asad (1900-1992) was born Leopold Weiss in Lviv, Ukraine to a family of Jewish Rabbi-clerics. He converted to Islam in 1926 while visiting the Middle East and became one of Islam’s most celebrated intellectuals. He wrote in the introduction of his translation of the Qur’an titled, The Message of the Quran:

...unlike any other book, the meaning and linguistic presentation of the Quran form one unbreakable hall. The position of individual words, sentences, the rhythm and sound of its phrases and their construction, the way the metaphors flow almost imperceptibly into a pragmatic statement, the use of acoustic stress not merely in the service of rhetoric but as a means of unloading, the unspoken but clearly implied ideas, all these make the Quran untranslatable a fact that has been pointed out by earlier translators and by all Arab scholars.

(Asad, iii)

Many believe that the Qur’an’s miracle lies in its recitation and hearing. The lyrical cadence of its language and rhythm carries a musical resonance that moves the listener regardless of whether they understand the Arabic language. As Tarif Khalidi puts it, “When recited, it flows with a sonority which common Muslim opinion holds to be capable of causing tears of repentance and comfort or else a shiver of fear and trembling.” (Khalidi, ix) Muslims today, as during the time of the Prophet, will often gather to hear the recitation of a Qur’anic verse, receive its spiritual blessings, and then discuss and debate its meaning.

Linguistically, the language of the Qur’an became the paragon of perfection in grammar, style, usage, syntax, and rhythm for the Arabic language and its literature. Christian monks in the Middle East, especially the Jesuits, famously studied the Qur’an so that they could excel in the Arabic language and its translation. Even in the modern age, famous Arab Christian scholars have excelled in the study of Qur’anic linguistics, becoming teachers and mentors for the Arabs. These include the Lebanese scholars Nasif Yaziji (1800-1871), Butrus (Peter) al-Bustani (1819-1883), the poet Maroun Aboud (1886-1962), and the linguist Emile Badi Yaqoub (Emile B. Jacob) (1950-).

Tafsir (Interpretation & Exegesis)

Accepted by Muslims as “The Word of God”, the text of the Qur’an has engendered an extensive body of scholarship, close readings, commentaries, and interpretations both Islamic and non-Islamic. The science and study of Quranic commentary, interpretation, and exegesis is called tafsir (from the Arabic fassara meaning to explain or elucidate). The resulting scholarship of tafsir is richly diverse in the variety and scope of interpretation and understanding of the Qur’an.

In the long history of tafsir and translation of the Qur’an, the Iranian-American psychologist and Sufi scholar, Laleh Bakhtiar’s (1938-2020) in 2007 produced a translation entitled The Sublime Qur’an that stands out for its devotion to linguistic consistency and gender neutral reading. Seeking to render into English the polyphony of the Arabic language of the Qur’an, Bakhtiar adopted the King James method of translation, called “formal equivalent”. In her words, “...it is the most objective kind of translation because you use the same word every time [it occurs]…” (Karmali, 50). One of few North American women to have translated the Qur’an, she also aspires to reproduce in her English version the gender neutral and inclusive language of the Arabic Qur’an. For example, the Arabic word in the Qur’an used to address humanity is al-insān. Now, the Arabic language has three classes of gender for its words, masculine, feminine, and neutral. However, the usual English equivalent for al-insān, mankind – does not capture this gender neutrality so Bakhtiar translates it as “humankind”. In addition, the word al-kāfirūn (sura 109), which is usually rendered as “the unbelievers” or “the infidels”, is translated by her as “the ungrateful”.

Some Islamic schools of thought, especially the Shia and Sufi mystical traditions, ascribe an inner and outer meaning to the Qur’an. That is, they believe that beyond the explicit linguistic meaning of the Qur’an lies a hidden or esoteric understanding. This interpretation of the inner meaning of the Qur’an is called taw’il.

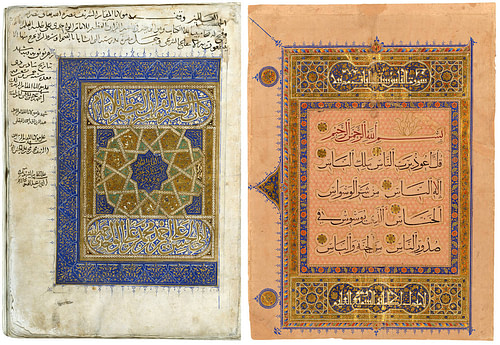

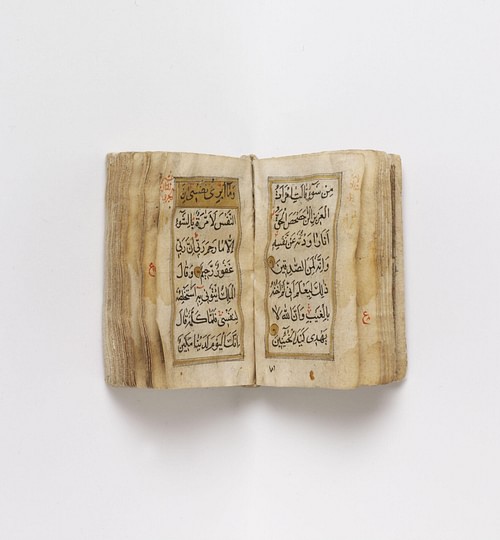

Calligraphy & the Arts of the Book

Islamic art is in many ways iconoclast – that is it does not include the kind of iconography that Christian art applies in a sculpture or painting of the Virgin Mary or Jesus Christ. Religious art is often inspired by the corresponding miracle of its prophet. Hence Islamic art is defined by the “aesthetic impulse” (Nanji, 150) to capture the linguistic and musical glory of the language of the Qur’an in written form. The verses of the Qur’an are copied out with the same diligence and reverence as is assigned to the reading, recitation, and study of the Qur’an. The mastery of the written word coupled with illumination and ornamentation has created copies of the Qur’an that are among some of the most prized and valued objects of sacred art. Many famous and celebrated copies of the Qur’an can be found in museums around the world.

Healing & Protective Powers

Many Muslims believe that the verses of the Qur’an have healing or protective qualities. In medieval times verses of the Qur’an were recited in the homes of the ill, at hospitals, and at births and deaths. Quotes from the Qur’an, the basmala or verses such as the ayat al-Kursi from surat al-Baqarah are inscribed on everyday objects – especially jewelry, and are believed to carry talismanic properties. Reciting verses of the Qur’an is understood as a means of beseeching the divine. In Muslim countries, children are sometimes sent to local mosques to learn to recite the Qur’an from memory. Someone who has memorized the whole Qur’an is called a hafiz.