Review

| Rating: | |

|---|---|

| Title: | Gods, Kings, and Merchants in Old Babylonian Mesopotamia (Publications de L'Institut Du Proche-Orient Ancien Du Colleg) |

| Author: | D Charpin |

| Publisher: | Peeters Publishers |

| Published: | 2015 |

| Pages: | 223 |

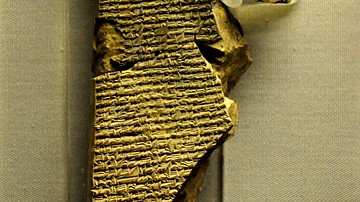

In Gods, Kings, and Merchants in Old Babylonian Mesopotamia, Dominique Charpin (Professor at Collège de France, Paris) examines the manners in which the religious, political, and economic spheres maintained fluid boundaries, often time intersecting. Within the work, he continue ideas began in his book Writing, Law, and Kingship in Old Babylonian Mesopotamia and offers valuable analysis of various topics pertinent to understanding ancient Mesopotamia, snapshots of ancient society through administrative documents, and is careful to note various places which need further in-depth studies. Drawing on studies from 1996 to 2015, he provides an excellent overview and up-to-date understanding of elements from the Amorite (or Old Babylonian) period (first half of the second millennium BCE). Much of his work is supported by the ARCHIBAB project, which is a French internet archive of a complete Old Babylonian bibliography and more than 32,500 texts.

Chapter One discusses prophetism in the Mari archives and, after establishing the error in distinction between prophecy and divination, argues that biblical prophecy is well in-line with its predecessor at Mari. Chapter Two analyzes extradition in the Amorite period and fleshes out the nuances of asylum and extradition with special focus on the authoritative role of gods in diplomatic records. Discussing evocation of the past, he then points to visions of the past, theological histories and temporal markers, to illuminate various approaches to and applications of the past. Chapter Four reviews the political and religious dynamics involving various kingdoms from the mourning of a king's death to a newly established king. Shifting to a broader look on the dead, Chapter 5 explores the relationship between the living and dead by examining literary texts and archaeology, emphasizing the nuances and multiple approaches of Amorite society regarding the dynamics between the living and dead. Chapter 6 surveys the role of gods as creditors, illustrating the human-deity dynamics in commercial and necessity loans. Chapter 7 briefly reviews the range of Amorite archival contracts and offers analysis of how fines and punishment, private and public spheres, and deity and human dynamics interact within a legal Amorite context. Finally, Chapter 8 re-evaluates archaeological studies of Mesopotamian elites households, suggesting new reasoning for household expansion, and provides a snapshot of house management and familial dynamics through archival records.

Without a doubt, Charpin's work is absolutely essential in a variety of aspects. Chapter One is the most intriguing. Moving beyond Martti Nissinen's four transmission elements of prophecy (sender, context, message, and recipient) from his well-known Prophets and Prophecy in the Ancient Near East (Atlanta, 2002), Charpin offers three additional, or alternative, understandings of the transmission of prophecy which take more seriously the various aspects of prophetism. These alternatives are important because they provide more tools for accurate readings of prophetic literature. Likewise, they are strongly convincing because they are directly rooted in the various pieces of prophetic materials from Mari. Unlike Nissinen, who approaches prophetic transmission fairly rigidly, Charpin successfully breaks from this mold to provide a more comprehensive and historically appropriate approach to interpreting and reading prophetic texts from Mari.

As a brief critique, Charpin would have done well to expand upon his brief discussion of school texts, as these reflect an even greater issue of the role of the scribal class in the Amorite period. Nick Veldhuis covers the topic of school texts and the scribal class quite extensively in his recent work about the history of the cuneiform lexical tradition (Ugarit-Verlag, 2014) and in an earlier work from 2010. Because we see developing scribal identity and traditions during the Amorite Period (or Old Babylonian), coverage of the role of cuneiform lexical lists in scribal identity would have strengthened Charpin's discussion regarding elite house management.

In conclusion, I highly recommend Charpin's work. The analysis in which he fleshes out the nuances and realities of the people and communities who wrote the various, often times administrative, texts effectively illuminates the world through the eyes of the elite during the Amorite period. More specifically, he is able to avoid creating artificial distinctions between religious, political, and economic elements and demonstrates how they all interact with each other. As an important note, though, the book is quite dense. Although it is a short read, just over 200 pages, it tends to focus on technical language often used in academia. It is still an excellent addition or supplement to projects surrounding, or even relating to, the Amorite period. Even more so, Charpin's work is helpful for research pertaining to the history and culture of Old Babylonian Mesopotamia.

Originally posted at The Biblical Review and now modified for the Ancient History Encylclopedia.

About the Reviewer

Cite This Work

APA Style

Brown, W. (2016, March 11). Gods, Kings, and Merchants in Old Babylonian Mesopotamia. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/review/110/gods-kings-and-merchants-in-old-babylonian-mesopot/

Chicago Style

Brown, William. "Gods, Kings, and Merchants in Old Babylonian Mesopotamia." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified March 11, 2016. https://www.worldhistory.org/review/110/gods-kings-and-merchants-in-old-babylonian-mesopot/.

MLA Style

Brown, William. "Gods, Kings, and Merchants in Old Babylonian Mesopotamia." World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 11 Mar 2016. Web. 12 Apr 2025.