Review

| Rating: | |

|---|---|

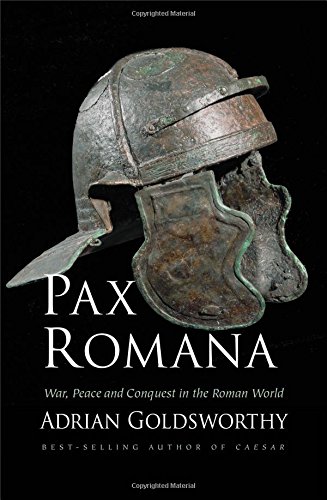

| Title: | Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World |

| Author: | Adrian Goldsworthy |

| Audience: | University |

| Difficulty: | Medium |

| Publisher: | Yale University Press |

| Published: | 2016 |

| Pages: | 528 |

In this book, Adrian Goldsworthy explains what the 'Roman Peace' really meant and explores the methods used to govern the vast Roman empire from the Republic to the Emperors. Beautifully written and filled with interesting analysis, this is not a book for newcomers to Roman history. University level readers will find it fascinating, however, as Goldsworthy makes connections they may never have imagined.

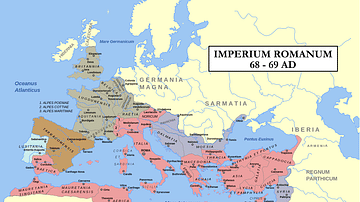

The Pax Romana, or Roman Peace, was the idea that the lands governed by the Empire enjoyed long-term stability and prospered because of their submission to Rome. Armies were sent to the frontiers to protect against the invasion of barbarians, whilst those inside the border happily donned the toga and quaffed wine by the gallon. This is the popular vision of Roman history – yet, as always, the truth is far more complicated, and in this book, Adrian Goldsworthy sets out to explore what the Pax Romana actually meant. Starting with expansion under the Roman Republic, he analyses the techniques the Romans used to control their vast territory right up until the Empire's final collapse in the 5th century CE. The scope of the book is ambitious, but luckily, Goldsworthy handles the wealth material with consummate skill.

The book begins by explaining why the Pax Romana is so interesting (not that any explanation is necessary). In the Preface, Goldsworthy points out that the period of Roman occupation was, for most nations, their longest interval without major war until modern times. He reminds the reader that our current peaceful lives in the West are a very modern phenomenon; only a generation separates us from the reality of living in wartime (i.e. in WWII). Similarly, peace was the exception in the ancient world. When Rome was in its infancy, Alexander the Great's successors were battling each other for supremacy, Gaulish tribes maintained a wasteland around their settlements to deter attacks, and banditry/piracy made travel highly dangerous. Rome's achievement in changing this status quo is, therefore, not to be sniffed at.

Whilst impressing this point on the reader, however, Goldsworthy swiftly acknowledges that the Pax Romana was not as complete as modern sensibilities might wish it to be. Quoting the Roman historian Tacitus, who famously quipped that Romans "create a desolation and call it Peace," Goldsworthy emphasises that all of Rome's achievements were built on the back of aggressive warfare. In the first part of the book, focusing on the Roman Republic, he describes the political landscape that fostered expansion and used, often, very thin justifications for declaring war. From the war with Carthage to the retribution meted out to raiding tribes, the Romans' capacity for brutality is well established. But even once wars had been won and provinces conquered, Goldsworthy shows us that peace was not inevitable. In subsequent sections, he goes on to analyse various rebellions that occurred through Roman rule and to pick apart the evidence that survives of banditry throughout the empire. His descriptions are full of interesting details, such as the fact that the Romans constructed watchtowers along the roads that were often manned by locals, not soldiers, and includes anecdotal evidence of mysterious disappearances from Pliny the Younger's letters to Trajan. The section of the revolts in Judea is also especially enjoyable since it includes the familiar tale of Jesus as seen from the Roman point of view.

Nevertheless, the overall argument of the book concludes that instances of rebellion were few and that banditry was far less than it had been in most places before the Romans had taken over. Goldsworthy also points out that the Romans' reputation in warfare (particularly their capacity to devastate peoples) enabled them to better promote peace. Using Caesar's conquest of Gaul to illustrate, Goldsworthy shows how the threat of the might of Rome encouraged communities to surrender to the Empire and aided negotiation. He also includes a sizzling analysis of the politics of the Gaulish tribes, who used the might of the Empire as a pawn in their own more local power struggles. We might like to think of our European ancestors as innocent victims of imperialism, but Goldsworthy paints them as being equally as manipulative and warlike as the Romans.

In the second part of the book, which looks at the reign of the emperors (or the Principate), Goldsworthy further develops this idea by demonstrating how the Romans used threats and diplomacy to dominate the provinces and their neighbours. He explains that rather than fully conquering the neighbouring power of Parthia, for example, the Romans were content for their enemies to make a show of submitting to Rome (for example by the King travelling to Rome to receive his crown from the Emperor) without this being a reality. The prestige mattered, but endless wars of domination were not necessary to achieve it. Another interesting discussion focuses on the organisation of Roman forts along the borders. Goldsworthy's pedigree as a military historian really comes into its own here as he breaks down the hierarchy of officers and explains what a soldier's daily life might be like in clear, entertaining prose. The stories of Hadrian's visits to castra in Africa add a touch of humour to humanise what might become a highly technical section of the book. The reason for explaining all this becomes obvious when Goldsworthy goes on to discuss how the Roman's counteracted raiding parties from beyond the provinces. This last point is especially important since it clearly shows the difference between life before the Pax Romana and during it. Where raiding parties could prey on vulnerable settlements with impunity before (indeed, some tribes looked on it almost as an occupation), under the Romans these groups were likely to be intercepted and punished before they made it home.

If one were to make any quibbles, it might be to complain that Goldsworthy has a habit of leaving out the names of specific scholars when referring to other studies or opinions. For the more curious reader, this can be frustratingly vague, but it is only a very minor point. Overall, however, this is a fantastic book – easy to read and utterly gripping right to the end. Goldsworthy makes exciting connections and brings together Roman history in a way a more linear study would struggle to do. For anyone wishing to give more depth to their timeline of Roman conquests, this book is a must.

About the Reviewer

Cite This Work

APA Style

Sahu, J. (2017, January 19). Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/review/157/pax-romana-war-peace-and-conquest-in-the-roman-wor/

Chicago Style

Sahu, Jasmine. "Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified January 19, 2017. https://www.worldhistory.org/review/157/pax-romana-war-peace-and-conquest-in-the-roman-wor/.

MLA Style

Sahu, Jasmine. "Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World." World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 19 Jan 2017, https://www.worldhistory.org/review/157/pax-romana-war-peace-and-conquest-in-the-roman-wor/. Web. 28 Apr 2025.