Review

| Rating: | |

|---|---|

| Title: | A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000-323 BC, 3rd Edition (Blackwell History of the Ancient World) |

| Author: | Van De Mieroop |

| Audience: | University |

| Difficulty: | Easy |

| Publisher: | Wiley-Blackwell |

| Published: | 2015 |

| Pages: | 436 |

Marc Van De Mieroop’s A History of the Ancient Near East is a superb book for students and general readers alike. Its crisp, clear narrative keeps the material lively while covering all of the important points. The third edition improves on a second edition that had already become a classroom standard.

Marc Van De Mieroop's A History of the Ancient Near East is a superb book for students and general readers alike. Its crisp, clear narrative keeps the material lively while covering all of the important points.

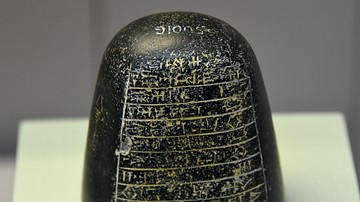

The third edition improves on a second edition that had already become a classroom standard. Expanded coverage of the Persian Empire is the most noticeable change, but some of the other changes are even more valuable for learners. A graphical timeline shows all the major events covered in the book, and each chapter begins with a section of the same timeline to show where it fits in the larger story. Sections labeled “Debates” are scattered throughout the book, discussing issues and evidence about which historians disagree. The debate sections have ample material for classroom discussions. A bibliography provides sources for papers or further reading. Over 60 photographs and illustrations enliven the text.

There are several ways to understand history, so it's hard to write a book that doesn't lose readers in a maze of complications. Should the book present a chronological sequence? Survey countries and their development? Examine political ideas, social institutions, migrations, and technological progress? List kings and battles? And most challenging, should it achieve clarity by telling a simple story while omitting mention of doubts, ambiguities, and conflicting evidence?

De Mieroop solves the problems by deft organization of his material. An introductory chapter defines the Ancient Near East and discusses its prehistory. It also gives an overview of some methodological issues. In the same chapter, a “debate” section explains the difficulty of dating ancient events and the various chronologies that historians use for the Ancient Near East. That debate section typifies the book's approach of putting complications off to one side so that the information is available but does not disrupt the main narrative. Similar sections throughout the book discuss source documents without getting in the readers' way.

Mesopotamia is at the center of the book's focus, which runs geographically from the Mediterranean in the east to Persia in the west, and from the Black Sea in the north to the Red Sea in the south. De Mieroop deliberately excludes Egypt except where it affects the main areas discussed in the book.

After the introductory chapter, De Mieroop divides the rest of the book into three parts, each of which covers an era characterized by a particular form of political organization.

Part 1, City States, covers the beginnings of civilization in Uruk, including the genesis of cities with social hierarchies, division of labor, and the development of writing. It artfully connects seemingly disparate phenomena to show how they fit together. For example, city-states required pottery that was concentrated within city boundaries. Remnants of the pottery, in turn, provide information for archaeologists about political and economic life. Larger territorial states and dynastic political organizations emerged alongside the older ways of living. Many of these social and political changes occurred at roughly the same times in different regions of the Ancient Near East.

Part 2, Territorial States, covers the emergence of larger political units that were made possible by earlier advances in writing and administration. As much as the territorial states varied — such as the Hittites, Babylonians, Assyrians, and Elamites — they shared common views about the proper ways to organize societies and empires. Larger political units led to greater inequality and concentration of wealth, which presented many of the same problems from one territorial state to another. That all came falling down at the end of the second millennium BCE, when for reasons not entirely clear, many of the mightiest states collapsed or went into decline. One of the book's “debate” sections discusses the unsolved mysteries of that process.

Part 3, Empires, covers the start of the first millennium BCE up to Alexander's conquest of the region. Two chapters cover the rise of Assyria, the building of its empire, and its inevitable fall. The Persian empire gets its own two chapters following the same structure, and a single chapter covers the Medes and Babylonians in that period.

Overall, De Mieroop's book is a clear and engaging survey of the Ancient Near East. Its exclusion of Egypt is unusual but is a defensible choice. Its integrated timeline, multitude of graphics, and separate sections about debates and documents make it a valuable resource for anyone interested in the period.

Cite This Work

APA Style

Palmer, N. (2017, April 19). A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000-323 BC (Blackwell History of the Ancient World). World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/review/160/a-history-of-the-ancient-near-east-ca-3000-323-bc/

Chicago Style

Palmer, N.S.. "A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000-323 BC (Blackwell History of the Ancient World)." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified April 19, 2017. https://www.worldhistory.org/review/160/a-history-of-the-ancient-near-east-ca-3000-323-bc/.

MLA Style

Palmer, N.S.. "A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000-323 BC (Blackwell History of the Ancient World)." World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 19 Apr 2017, https://www.worldhistory.org/review/160/a-history-of-the-ancient-near-east-ca-3000-323-bc/. Web. 25 Apr 2025.