Review

| Rating: | |

|---|---|

| Title: | Romanland: Ethnicity and Empire in Byzantium |

| Author: | Anthony Kaldellis |

| Audience: | Professional |

| Difficulty: | Hard |

| Publisher: | Harvard University Press |

| Published: | 2019 |

| Pages: | 373 |

Kaldellis’ Romanland is a study on ethnic identity in the Byzantine Empire, arguing that the Byzantines had a Roman identity and ethnicity centered around the Roman nation of Romanía. While aimed at scholars familiar with Byzantium, Romanland is a groundbreaking work that brings Byzantine Studies into the modern age by looking at Roman ethnicity in relation to Romanía’s minorities and engaging with modern understandings of ethnicity, empire, and the nation.

Those familiar with Byzantine history are aware that the Byzantines referred to themselves as Romans and lived in what they still considered the Roman Empire, or Romanía. But despite this well-known fact, Byzantinists have long avoided directly engaging this question of the Byzantines' Roman identity. In Romanland, Byzantine history professor Anthony Kaldellis tackles this question, arguing that not only was Roman the identity of the Byzantines but that Roman was also an ethnicity.

The first part of Romanland begins by recognizing the history of denial of Roman identity by Byzantinists, a type of “cognitive dissonance” of knowing that Byzantium was the Roman Empire but refusing to seriously acknowledge it. It then defines the contours of the Roman ethnicity, including both poor and rich Romans, men and women, all occupations, and all parts of the empire; in other words, the size and shape of an ethnic group or nation, while excluding other recognized ethnic groups such as the Franks and Armenians. Key indicia of the Roman identity included their homeland, their ancient predecessor language of Latin and contemporary language of Romaic, and their Orthodox Christian religion. Romanía, or Kaldellis' titular Romanland, was the homeland and territory of the Romans, a “state named after a people” (93).

The second half of the book turns to the process of Romanogenesis, or how “others” were assimilated into Romans. In case studies on Khurramites, Muslims, and Slavs, Kaldellis identifies a variety of factors that contributed to assimilation, including conversion, the institution of the Orthodox Church and Greek liturgy, marriage to Roman women, and resettlement in smaller groups. Kaldellis then pushes back against the theory of Armenians being a distinct ethnicity within Byzantium that never assimilated, instead hypothesizing that there is a spectrum of identity from Armenian to Roman (with possibly a vague knowledge of Armenian ancestry), which was assisted through assimilation practices such as converting to Orthodox Christianity and adopting more Roman-sounding names.

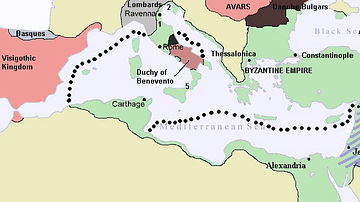

Romanland finally looks through the lens of this revised understanding of Roman ethnicity to determine if Byzantium really was an empire by modern interpretations of the term. Kaldellis determines that Romanía was not an empire in 930 CE and, instead, was much closer to a national state. In 1064 CE, Romanía had its greatest amount of ethnic diversity, but it was still an ethnically Roman core with a few ethnically diverse conquests at the edges.

Romanland is a substantial contribution to the field of Byzantine Studies, making a convincing argument for what was for so long the hidden elephant in the room of Roman ethnicity. Kaldellis amply supports his propositions with a wide range of sources from across the early and middle Byzantine periods, as well as earlier Roman sources and those of neighboring peoples such as the Arabs, Armenians, and Franks. In addition, his approach weaves in elements of modern understandings of ethnicity and empire to better develop our collective understanding of the Byzantine Empire.

The book is directed towards a scholarly audience familiar with Byzantium, but Kaldellis does try to improve readability by making references to the United States, including to diversity at his own Ohio State University and even stating “make Rome great again” (155). Kaldellis does make a mistake by saying that Maria of Amnia married Leo IV (in reality she married Leo's son, Constantine VI), but this is a stark error in an otherwise very convincing study (171). His force in arguing for Roman ethnicity can occasionally be to the detriment of other agendas, such as when he says that Basil I's (r. 867-886 CE) “actual ancestry is irrelevant,” which might be the case for Romanland but certainly has value for other points, especially since there is proof of Basil using his Armenian ancestry for connections (192). These minor cautions, however, do not affect the overall value of Romanland as a soon to be seminal work on Byzantine/Roman ethnicity, empire, and nationalism.

About the Reviewer

Cite This Work

APA Style

Goodyear, M. (2020, January 09). Romanland: Ethnicity and Empire in Byzantium. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/review/222/romanland-ethnicity-and-empire-in-byzantium/

Chicago Style

Goodyear, Michael. "Romanland: Ethnicity and Empire in Byzantium." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified January 09, 2020. https://www.worldhistory.org/review/222/romanland-ethnicity-and-empire-in-byzantium/.

MLA Style

Goodyear, Michael. "Romanland: Ethnicity and Empire in Byzantium." World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 09 Jan 2020, https://www.worldhistory.org/review/222/romanland-ethnicity-and-empire-in-byzantium/. Web. 26 Apr 2025.