Review

| Rating: | |

|---|---|

| Title: | India in the Persianate Age: 1000–1765 |

| Author: | Richard M. Eaton |

| Audience: | University |

| Difficulty: | Easy |

| Publisher: | Univ of California Pr |

| Published: | 2019 |

| Pages: | 488 |

This is a groundbreaking work on the middle period of Indian history. It shows how hidden assumptions dominated the thinking of colonial rulers and let nationalists prevent a realistic assessment of an important phase of Indian history. Far from being a dark period, it witnessed a high level of sociocultural exchange and economic vitality. Under the Mughals, India became an economic superpower. I would highly recommend this work to both general readers and specialists in Indian history.

Richard Eaton’s India in the Persianate Age: 1000-1765 represents a paradigm shift in the study of Indian history. It debunks the stereotypical interpretation of the middle period of Indian history, first championed by the British and later by Indian ultranationalists, as one of Hindu-Muslim conflict and backwardness. Eaton argues that far from being a period of religious sectarianism, conflict, and decline, India under the Turkic and Mughal rules represented a period of intense engagement, assimilation, and growth. Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni’s invasions beginning in 1000 CE introduced the Persianate culture to India. This book analyzes this period in the context of a new Persianate culture that grew out of the interaction with Arab Islam and pre-Islamic Iranian traditions and then served as a cultural umbrella across a huge swath of the Iranian plateau and Central Asia.

According to Eaton, the Persianate culture crossed paths with Sanskrit Cosmopolis, a transregional culture based on Sanskrit canons that had spread through much of South and Southeast Asia. The overlap of these two traditions brought about far-reaching changes in South Asian political, social, and cultural life. India became the principal center of producing Persian works, including dictionaries and the first major anthology of Persian poetry. By the 14th century, Persian had become the most widely used language for governance across South Asia as Indians came to fill the vast revenue and judicial bureaucracies.

More often than not, new rulers adopted policies in conformity with the existing cultural norms. Thus, when the Delhi Sultanate’s rulers issued coins, they did so in accordance with indigenous numismatic tradition. The process of assimilation accelerated under the Mughals. Dara Shikoh, the Mughal prince, ordered the translation of the Upanishads into Persian and claimed to have found roots of all monotheistic religions in them. Eaton argues that the Great Mughals had set India on a “path to modernity” well before the onset of European colonial rule.

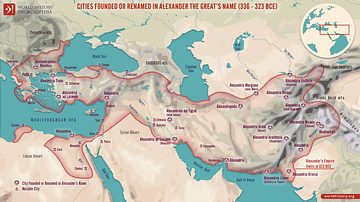

Written in clear and concise language, this book should appeal to both history experts and enthusiasts. The book progresses through eight chapters. The Introduction presents the conceptual framework of the work, and the Conclusion brings all the threads together in supporting the book’s hypothesis. Each chapter is supplemented by extensive notes and is followed by a summary for a comprehensive recap of the material. Eaton draws from diverse primary sources, such as the writings of the Persian polymaths Ibn Sina and Al-Biruni and the Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta. A series of eight maps help readers to visualize the growth of Turkic and Mughal political power, and 21 illustrations display the extent of the Persianate-Sanskritic interaction in art, architecture, painting, and coinage. It may be worthwhile to observe that the India-Persia connection goes back to ancient times and a brief review of it might have been a nice backdrop to the current work. Ashoka (c. 268-232 BCE), the third emperor of the Maurya Empire, had installed one of his famous edicts on righteous living in Kandahar - on the doorstep of Persia. One can read a resemblance between his message of ethical living and the Persian concept of justice. In addition, India’s music genres of Khayal, Ghazal, Qawwali, Dhrupad, and Tarana are heavily indebted to the Persian legacy, and a greater focus on this musical aspect would have added a valuable dimension to this book.

India in the Persianate Age is an extraordinary work of rigorous and fact-based research by one of the foremost historians of pre-colonial India. Eaton is Professor of History at the University of Arizona. His book is valuable for historical discussions even beyond India, especially during a time when the manipulation of history has become increasingly commonplace.

About the Reviewer

Cite This Work

APA Style

Chaudhuri, S. (2022, December 14). India in the Persianate Age: 1000-1765. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/review/314/india-in-the-persianate-age-1000-1765/

Chicago Style

Chaudhuri, Shankar. "India in the Persianate Age: 1000-1765." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified December 14, 2022. https://www.worldhistory.org/review/314/india-in-the-persianate-age-1000-1765/.

MLA Style

Chaudhuri, Shankar. "India in the Persianate Age: 1000-1765." World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 14 Dec 2022, https://www.worldhistory.org/review/314/india-in-the-persianate-age-1000-1765/. Web. 21 Apr 2025.