Review

| Rating: | |

|---|---|

| Title: | Destroying to Replace: Settler Genocides of Indigenous Peoples |

| Author: | Mohamed Adhikari |

| Audience: | University |

| Difficulty: | Easy |

| Published: | 1970 |

| Pages: | 179 |

"Destroying to Replace" is a compelling book that focuses on the impact of settler colonialism over the course of nearly 600 years. The author Mohamed Adhikari utilizes four case studies from around the globe to demonstrate that genocide was not an unintended consequence of colonialism but an intentional action perpetrated by colonial settlers. This work should be of interest to educators who want to engage students in conversation about the impact of European colonization.

Historical works on settler colonialism and genocide are voluminous, but there are relatively few, if any, works of synthesis geared to advanced high school and undergraduate students. Happily, the author Mohamed Adhikari, Professor of History at the University of Cape Town who spent his career researching the impact of settler colonialism around the globe, provides a succinct but compelling introduction through four carefully selected case studies on indigenous peoples in the Canary Islands, Queensland, California, and German South West Africa (GSWA).

In an introductory chapter, Adhikari provides crucial background on the origin of the term genocide from the work of Polish jurist Raphael Lemkin to the adoption of the legal definition adopted by the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (UNCG). He makes a persuasive case that students should focus on the intention of settler regimes to “destroy and replace.” In other words, genocide was not a byproduct but a deliberate action carried out by colonial settlers.

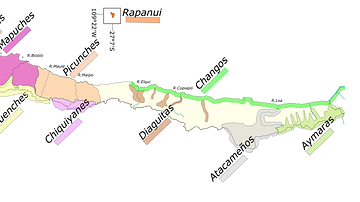

Over four chapters, Adhikari gives background on each indigenous society prior to colonialism and develops a useful two-stage frontier framework to help explain how settler actions resulted in genocide. In the “slaughterhouse frontier” phase, control for land and resources was the fundamental reason behind genocidal practices. Spanish subjugation of the Canary Islands (Chapter One) took nearly a century, and the most lucrative “commodity” was the indigenous inhabitants themselves. By the 16th century, mass enslavement and deportation of captives demonstrated the Spanish intent to rid the islands of native inhabitants and replace them with a Western settler economy. The obliteration of Canarian society set an important precedent that “foreshadowed the holocaust that was to engulf the New World” (21). In Queensland (Chapter Two), the environmental destruction resulting from grazing and mining operations led to Aboriginal resistance, which ultimately resulted in mass killings. This was a similar pattern in California (Chapter Three) following the discovery of gold in 1848. Here, Adhikari traces the rush of overlanders that came “heavily armed, brimming with Indian-hatred” (81) and intended to claim the best land for themselves. Economic motivations were less important in GSWA, however, increased settler competition for grazing land with the Herero people and German ideas of racial superiority fueled conflict. The German General Lothar von Trotha, with the tacit support of the Kaiser, exploited inter-chief rivalries and utilized superior industrial weaponry to crush the Herero people.

In each case, the intention to destroy the indigenous communities was ever-present. The colonial government in Queensland promoted squatter interests and refused to prosecute those charged with killing Aborigines. Most surprisingly, the Queensland government funded the Native Police Corps, a paramilitary force of Aboriginal troopers under the command of white officers charged with patrolling the frontier and operated as mobile death squads. In California, legislation within the new state government denied Native Americans basic human rights or citizenship, and mass violence was institutionalized through the collaboration of vigilante gangs, state volunteer militias, and notably the U.S. Army. To Adhikari, the destruction of the Herero people in GSWA is the clearest example of genocide given Trotha’s 1904 extermination proclamation.

In the “post-frontier” phase, Adhikari emphasizes that settler colonists were generally less violent because they didn’t feel as threatened by indigenous peoples. However, their actions furthered the genocidal process. Settler regimes utilized practices ranging from forced conversion to Christianity and child confiscation to the sexual exploitation of women and children. The spread of diseases and the construction of reservations (in Queensland and California) and concentration camps (in GSWA) proved especially catastrophic.

Destroying to Replace is a model of teaching-oriented historical writing that also provides an impressive collection of historical documents and questions for consideration interwoven in each chapter. A close reading of these primary sources would enhance any world history or genocide studies classroom and provoke wide-ranging conversations on significant themes related to the impact of settler colonialism. Additionally, Adhikari’s framework for assessing genocide would also prove valuable for teachers looking to incorporate additional case studies into their courses.

About the Reviewer

Cite This Work

APA Style

Harris, B. (2023, July 27). Destroying to Replace: Settler Genocides of Indigenous Peoples. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/review/376/destroying-to-replace-settler-genocides-of-indigen/

Chicago Style

Harris, Benjamin. "Destroying to Replace: Settler Genocides of Indigenous Peoples." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified July 27, 2023. https://www.worldhistory.org/review/376/destroying-to-replace-settler-genocides-of-indigen/.

MLA Style

Harris, Benjamin. "Destroying to Replace: Settler Genocides of Indigenous Peoples." World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 27 Jul 2023, https://www.worldhistory.org/review/376/destroying-to-replace-settler-genocides-of-indigen/. Web. 24 Apr 2025.