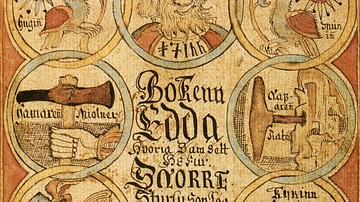

The Old Norse word saga means 'story', 'tale' or 'history' and normally refers specifically to the epic prose narratives written mainly in Iceland between the 12th- and 15th centuries CE, covering the country's history as well as Scandinavia's legendary past. A few sagas were also written in Norway but in either country their usually anonymous writers shaped their stories in high-quality, nuanced prose, leading the saga to now be considered one of the prime vernacular literary genres of Medieval Europe. Poetry is generally included, too, which helps point out the influence older, oral traditions of storytelling are thought to have had on the saga's development.

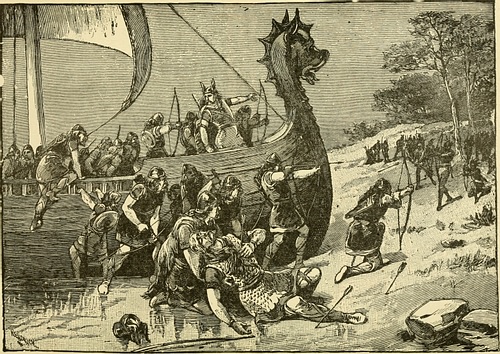

Although the heyday of Old Norse saga composition lay in the 13th century CE, the tales often dive back through the ages into the times of ancestors, heroes and legendary kings, spanning from prehistory through the Viking Age (c. 790-1100 CE) – including the settlement of Iceland – to the writers' own times. History and fiction are often mixed in a sort of Gordian knot that is hard to disentangle, and the stories have as their playground not just Iceland but also Scandinavia, the British Isles, the North Atlantic (including Greenland and North America), the Mediterranean, Russia and the Middle East.

In our present day sagas are not only perfectly readable and enjoyable but also still feel relatable, probably due to the fact that they focus on the everyday life of everyday people. Wealthy farmers, for instance, get tangled up in such things as feuds, go on exciting and often character-shaping journeys, or experience a variety of down-to-earth problems from within the predominantly agricultural society they are a part of.

The Old Norse sagas can be arranged into the following main subgenres, each with their own favourite topics and features, which are frequently referred to by their Old Norse name by scholars:

- Fornaldarsögur – 'Legendary sagas', 'Sagas of ancient time' or 'Mythical-heroic sagas'

- Riddarasögur – 'Sagas of knights'

- Konungasögur – 'Kings' sagas'

- Íslendingasögur – 'Sagas of Icelanders' or 'Family sagas'

- Samtíðarsögur – 'Contemporary sagas'

Origins of the saga

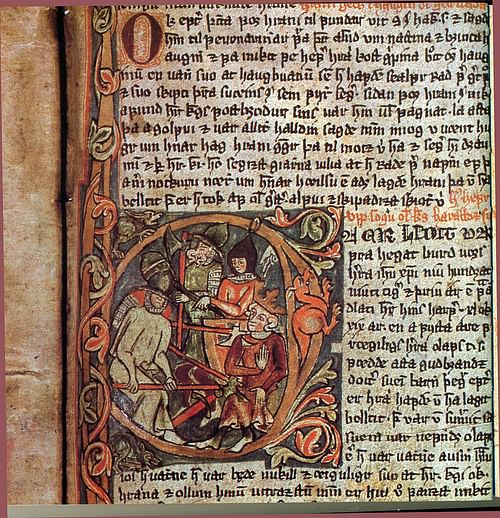

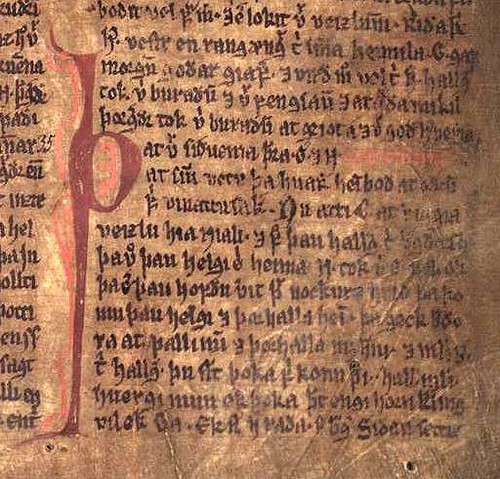

The quest for the origins of the Old Norse saga takes us beyond the realm of the tangible collections of parchment that prevail from the 13th century CE onward and into a murkier, harder-to-trace past. Before 1250 CE, only a few sagas can be proved to have existed in writing – Egils Saga, telling of the life of the Viking Age poet Egill Skallagrímsson, is one of them – and these fragments allow us to pin down the (late?) 12th century CE as the likely beginning of the textualisation process. From this time onwards, saga composition probably became an exclusively Icelandic phenomenon, and it is from 1350 CE and beyond that the majority of our extant manuscripts originate.

As for what exactly prompted the process or where the stories first came from, we can only hazard educated guesses. In the early 20th century CE, Swiss scholar Andreas Heusler came up with two alternatives that long divided the academic community: on the one hand, the 'freeprose theory' suggested the sagas were essentially oral texts handed down through generations before being recorded in writing in the Middle Ages, while on the other hand, the 'bookprose theory' held that the sagas were created in the Middle Ages, although partially based on oral sources. Today, neither is deemed sufficiently accurate, but the valid takeaway is their shared emphasis on the existence of an oral tradition that fed into the later, written one – something present-day scholars actually agree on.

This oral tradition hails back at least to the Viking Age, when poetry was often performed for the elite. As a lot of the sagas take place on a Viking Age stage, too, it is not hard to envisage some Viking Age stories surviving orally until medieval authors picked up on them and shaped them into their own written versions. The Icelandic scholar Gísli Sigurðsson even explains that 'oral traditions continued to feed into written ones throughout the period of Icelandic saga composition.' (Clunies Ross, 47-48). Although Iceland was already Christian by this time, Icelandic (Old Norse) was the favoured written language and this also goes for the sagas. This love for the vernacular ties in with a broader Western European context, too: from the 12th-14th centuries CE, a vigorous textual, vernacular culture flourished there, and its courtly romances and other works may well have reached Scandinavia, perhaps soliciting a response or impacting saga composition.

The Age of Saga

Iceland was first settled by Scandinavians – mainly from Norway – during the so-called Age of Settlement (c. 870-930 CE), in which families began building the farmsteads and rural communities that would remain central for centuries. It is in the following, aptly-named Age of Saga (930-1030 CE) that many of the Old Norse sagas are set. By 930 CE, Iceland had been divided into 36 principalities, each with its own chieftain to represent it at the assembly (Althing). Iceland was Christianised in 1000 CE and churches became part of the Icelandic landscape, too, though pagan beliefs and customs did not vanish entirely or instantly. Communes existed along the coasts where people owned their own land, farmed it, raised cattle on it, fished, hunted and traded – in short, life took place outdoors. The best farmers could be very wealthy indeed and controlled not just labour, production and property but also defined social customs. In the absence of a centralised executive judiciary arm, feuds were often settled by the parties that were directly involved – a theme that pops up in many sagas.

The beginnings of the written saga tradition overlap with the Age of the Sturlungs (1200-1262 CE, after which Iceland came under Norwegian sway). Chieftains had grown ever wealthier and more powerful, adding other communes to their own, and eventually six family clans ended up in power, with the Sturlungs holding the largest slice of the Icelandic pie. Daily life was not that different from the Age of Saga, though; medieval Iceland was still a small-scale, agricultural society in which honour played an important part and feuds erupted. It would thus not be a huge imaginative exercise for the 13th-14th century CE saga writers to understand and depict Age of Saga-societies, although they obviously brought their own, medieval attitudes to the table, too. Most obviously, the sagas present a view of history and geography that follows suit with medieval Christian ideology, but their composers give them a distinctly Icelandic coating and preserve an older outlook on events of the past and present, too, all the while creatively filling in any gaps in their knowledge.

Characteristics

Although sagas come in different shapes and forms that can be arranged into a variety of subgenres, a somewhat heroic effort can still be made to create a generalised overview of what characterises the Old Norse-Icelandic saga. Sagas tend to tick the following boxes:

- An oral tradition lies at their roots and impacted them;

- They were mainly written down between the late 12th-15th centuries CE, with the 13th century CE forming the heyday of saga composition;

- Most are Icelandic (a few are Norwegian);

- Most are anonymous;

- They are written in the vernacular (Old Norse);

- Most sagas use both prose and (some) poetry;

- Their narrative follows a more or less chronological order and general pattern;

- They often contain a mix of history and fiction that can be hard to disentangle;

- They are told from a Christian point of view but with genuine admiration for the pagan past;

- Their focus lies on everyday life and their social reach is inclusive;

- They are thought to have been performed or read aloud.

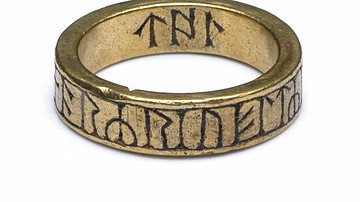

The poetry mentioned here usually refers to so-called skaldic (courtly) poetry, which is notoriously difficult and was a hallmark of the Viking Age, during which skalds (poets) performed at courts in front of the elite. Such poetry normally does an excellent job at standing the test of time because its stanzas could be learned by heart and handed down through generations of storytellers. It is thus the poetic elements of the medieval sagas that are thought to contain the earliest and most reliable references to another time. Poetry plays an especially large role in the konungasögur ('kings' sagas') subgenre and is thought to have spread from there into other genres. Although some sagas contain only a tiny bit of poetry or none at all, most mix the use of prose and poetry.

Unlike the earlier skalds, most saga authors were anonymous. Their tales were intended to draw the reader (or listener) into the world they depicted, its people, events and ideas coming alive. The person who shaped these things into a story mattered less – he was a compiler, not a creator, relaying stories that were part of a long tradition. Robert Kellogg explains the following about the saga author:

He derives his authorial authority not from the originality of his style or story but from his fidelity to the events, or to others' accounts of them and their judgements on those who were involved – in other words, to what has been said. (Smiley e.a., xxiv).

Saga authors were certainly not untalented: their prose has been praised as being sophisticated, fluent, and nuanced, and often showing a good sense of humour and wit. The author of Njáls saga, for instance, flaunts a somewhat dark sarcasm when he describes how Njáll's son Skarphéðinn witnesses servants of his mother and Gunnar's wife, Hallgerd, carrying out a series of household killings. Skarphéðinn remarks that the 'Slaves are a lot more active than they used to be.' (Ch. 37) and that 'Hallgerd does not let our servants die of old age' (Ch. 38) (both quoted from Smiley, xxvi).

Sagas were probably performed or read aloud to a general public, perhaps at gatherings or simply at home on the farm, although the specifics surrounding this are shrouded in mystery. With stories that focused on everyday life, sagas were not limited to the courtly audience of earlier poetry but appealed to Icelandic society at large. Of course, some bigshots like King Sverre Sigurdsson of Norway (r. 1184-1202 CE) clearly commissioned their own sagas, recording their own lives in a way that made them look decent, and it is likely that so did some heads of Icelandic families intent on celebrating their families' deeds and history. Genealogies were very popular, indeed.

The topics that prevail across the saga genre in general thus include, not surprisingly, the definition of heroes who are often wealthy and/or powerful farmers. In fact, against the backdrop of an agricultural society in which life was tough and busy, sagas tell the stories first and foremost of people, be they Scandinavian kings or more mundane members of Icelandic families living in a certain corner of the island.

Despite a few strong and independent women also cropping up, the world of the sagas is a man's world. It is also certainly one in which characters are anything but flat: they speak up, make their intentions clear, judge others, are judged themselves, take rash action or seek soul-quenching revenge. No courtly etiquette obscures the way people speak their minds. Given shape in a more or less chronological order, a lot of sagas tend to follow a similar pattern: first, the main characters are introduced in their geographical and historical settings (family and such); everyday life events such as marriages, inheritances, or robberies lead to conflict; this results in vengeance and people, even family members, being pitted against each other; and eventually there is reconciliation.

Although certain elements of the sagas do not hold up against our more reliable archaeological or historical evidence – for instance, their depiction of pagan religion is quite distorted and their view of kings or heroes often idealised – the sagas are great sources when you want to study the mentality, social structure, farm life and everyday customs in Old Norse society, which was similar enough between the Viking- and the Sturlung Age to tell you a little bit about both.

Subgenres

Most sagas can be grouped together under the headers of the following subgenres, which unsurprisingly all have their own favourite main topics and ways of sorting out the historical and geographical setting. Of course, some things were so popular they occur across various genres, like the genealogies which often have a direct bearing on the story by alluding to the power of a hero's illustrious ancestor or, conversely, to the main character's famous descendants. The motif of travel is also found all over the place, which is logical enough in a setting such as Iceland with its scattered farmsteads and from which one could not exactly swim to the nearest neighbouring country either. It is not hard to imagine the life skills and knowledge a protagonist would gather on an adventurous journey abroad.

Fornaldarsögur

Fornaldarsögur ('Legendary sagas', 'Sagas of ancient time' or 'Mythical-heroic sagas') are legendary sagas that put Scandinavian heroes and figures of a time before the settlement of Iceland (c. 870 CE) into the limelight. They often have Icelandic descendants and their stories are often laid out in a biographical narrative scheme. Typically, the story begins with the hero's parentage and childhood, relating his adult-life adventures and feats of strength in the face of various often monstrous or supernatural adversaries. Travel plays an important role. Conveniently for the hero, he often wins a bride somewhere along the way, before his story is concluded with for example his return home, his fulfillment of a prophecy of his death, or his death away from home.

Some examples of fornaldarsögur: Bósa saga ok Herrauðs ('The Saga of Bósi and Herrauðr'), Hrólfs saga kraka ('The Saga of Hrólfr Pole-ladder'), Ragnars saga loðbrokar ('The Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok'), Vǫlsunga saga ('The Saga of the Volsungs').

Riddarasögur

Riddarasögur ('Sagas of knights') are romances either translated from existing European works or indigenous ones, in both cases usually depicting Scandinavian knights or nobles in a European setting (although sometimes ranging beyond Europe to, for instance, Asia). There is no specific time-setting, though the translated knight's sagas usually take place in the time of the legendary British King Arthur. The same biographical narrative scheme we find in the fornaldarsögur is also found here, with a similar cycle of a hero's upbringing and adventures, monster-slaying and dramatic death, with travel again being an important feature.

Some examples of riddarasögur: Karlamagnús saga ('The Saga of Charlemagne'), Tristrams saga ok Ísǫndar ('The Saga of Tristan and Iseult'), Sigrgarðs saga frœkna ('The Saga of Sigrgarðr the Brave').

Konungasögur

Kings' sagas eternalise the lives of kings of Norway and, to a lesser extent, those of Denmark and the jarls of the Orkney islands, who reigned during the Viking Age and through to the late 13th century CE. Besides Scandinavia itself, the British Isles, Europe and the Middle East also crop up in terms of geographical settings. The sagas' largely biographical structure unsurprisingly includes the king's childhood and adulthood, focusing on key moments such as the assumption of the throne, conflicts and an account of how the king met his end, usually in a bloody way on the field of battle. Sometimes the king's mother's pregnancy is included, or even a premonition hinting at the child's impending greatness. Konungasögur are partially inspired by earlier skaldic poetry composed specifically for kings and their writers probably had access to anecdotes.

Some examples of konungasögur: Flateyjarbók ('Book of Flatey', compilation), Heimskringla ('Circle of the World', contains biographies of kings of Norway), Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar ('The Saga of King Olaf Tryggvason'), Orkneyinga saga ('The Saga of the Orkney Islanders').

Íslendingasögur

Íslendingasögur ('Sagas of Icelanders', 'Family sagas') are – true to their clear-cut name – stories dealing with Icelandic families mainly within the context of their farm homes during the Iceland of the Age of Settlement (c. 870-930 CE) up to the period surrounding the island's conversion to Christianity (c. 1000 CE). Here, they interact with fellow Icelanders, journey to Scandinavia, Europe, the Middle East, or even Greenland and North America (Vinland). Feuds, and the concepts of honour and shame, are a central theme, and the stories' narratives are often complex in structure and language. Subgroups are the lives of skalds and sagas of outlaws.

Some examples of íslendingasögur: Egils saga Skallagrímssonar ('The Saga of Egill Skallagrimsson'), Eiríks saga rauða ('Erik the Red's saga'), Laxdæla saga ('The Saga of the People of Laxdale'), Njáls saga ('The Saga of Njáll').

Samtíðarsögur

Samtíðarsögur are contemporary sagas that, unlike the others, actually concern the writers' own times (or close to it, at least). Mainly set in the Iceland of the 12th and 13th centuries CE, these sagas focus on the most powerful Icelandic families that were around at the time and preserve their successes, conflicts and activities. Feuds are once again an important element. Subgroups are Sturlungasögur ('Sagas of the Sturlungs) and Biskupasögur ('[Icelandic] bishops' sagas').

Some examples of samtíðarsögur: Íslendinga saga ('The Saga of the Icelanders'), Sturlu saga ('The Saga of Sturla [Þórðarson]'), Þorgils saga ok Hafliða ('The Saga of Þorgils and Hafliði').

Conclusion

Sagas remained popular in Iceland well beyond the Middle Ages, despite intermittent attempts to ban saga reading between the 16th- and 19th centuries CE by a more conservative clergy of the Icelandic Reformed Church. By the mid-19th century CE, the saga's advance had become unstoppable as it became a symbol of a sort of nostalgic golden age within Iceland, and as outside of Iceland the professional study of the Old Norse-Icelandic language and literature came into being. Thus, Iceland's beautiful, medieval take on Scandinavia's legendary and historical past survives into the present day for us all to enjoy.