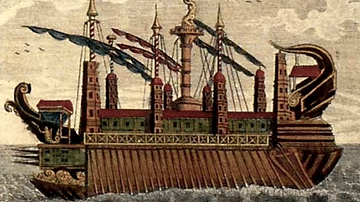

The trireme (Greek: triērēs) was the devastating warship of the ancient Mediterranean with three banks of oars. Fast, manoeuvrable, and with a bronze-sheathed ram on the prow to sink an enemy ship, the trireme permitted Athens to build its maritime empire and dominate the Aegean in the 5th century BCE.

Most scholars credit the Phoenicians with first inventing the trireme which was itself an adaptation of the earlier bireme. According to Thucydides, it was the Corinthians who first adopted triremes on the Greek mainland c. 700 BCE. However, it was the Athenians, with their newly found wealth from local silver mines, who constructed a fleet of triremes large enough to hold sway over the Aegean.

Rowing Arrangement

The trireme was so-called because of the arrangement of rowers in three lines down the length of each side of the ship. Concrete archaeological evidence is lacking and scholars debate the exact arrangement; however, from depictions on ancient carvings and pottery and references from classical authors such as Homer, Thucydides, and Apollonius of Rhodes, a wide consensus has been reached. As many as 30 oars, each with a single oarsman, ran the length of the ship in three tiers. Consequently, the total number of rowers could have been between 170 and 180, allowing a speed of as high as nine or ten knots in short bursts. Each oarsman had a fixed seat (and leather or wool cushion) and the rowers were arranged with 31 on the top row (thranoi), 27 in the middle (zygoi), and 27 on the lowest level (thalamoi). Their 4 m long oars were attached to a tholepin (fixed vertical peg) with a leather oar-loop.

Archaeological remains of boathouses, most notably at Piraeus, indicate that the maximum length of the ship would have been around 37 m with a beam of 6 m. They measured about 4 m from deck to keel and may have weighed as much as 50 tons. However, this was light enough so that crews could carry the vessel if necessary and easily beach it overnight.

Materials

The Greek ships were built using softwoods such as pine, fir, and cypress for interiors, and oak only for the outer hulls. Oars were made from a single young fir tree and measured some 4.5 metres in length. As a consequence of using lighter woods, the ship was highly manoeuvrable. The full-size reconstruction Olympias built in the 1980s CE has demonstrated that a trireme could turn 360 degrees in less than two ship's lengths and turn 90 degrees in a matter of seconds in only a ship's length. The vessel also displayed impressive acceleration and deceleration rates.

The disadvantage of softwoods is their high absorption of water, and therefore the ships were usually pulled out of the water at night using slipways and then housed in protective huts. The technique used in construction was to lay down longitudinal beams joined by dowel pin-joints along an oak keel. These were then covered with the outer hull, a sheath of closely fitting (but not overlapping) planks sealed with pitch and resin. The hull was made smoother by adding wax to the pitch which added to the speed potential of the vessel. Ribs (zyga) and arrangements of tightened ropes (hypozomata) were then fixed inside to add strength to the overall structure. Finally, a simple flat deck (without rails) was added with a central space running down the length of the ship, giving access to the interior.

In addition to trireme rowers, the ship was equipped with a square sail of papyrus or flax (or sometimes two), used when cruising and taken down and stored on land when in battle conditions. Steering was achieved through two steering oars at each side of the stern and controlled by a single helmsman (kybernetes). Next to the helmsman stood the ship's commander (trierarchos), and both were protected by the upward curving structure at the stern known as the aphlaston. Other crew members were the rowing master (keleustes) who shouted instructions, the 'bow officer' (prorates) who relayed those instructions further down the ship, a piper (auletes) who kept time for the rowers playing an aulos, a carpenter (naupegos), and deck crews to man the sails.

Prows were often decorated to resemble animal heads, and a common feature was the attachment of large, painted marble eyes. The hull itself was painted with waterproofing pitch, giving the distinctive black appearance so often referred to by Homer. Ships were regarded as females and also given names, for example, Artemis, Equality, Sea Horse, and Good Repute.

Military Use

The principal weapon of the trireme was the bronze-sheathed battering ram affixed to the prow which was used to sink enemy ships. These often took the form of animals, for example, the head of a goat. However, ramming would have rarely sunk an enemy vessel and an important secondary strategy was boarding the enemy ship. For this reason, the typical Athenian crew included a complement of ten hoplites and four archers.

![Greek Trireme [Artist's Impression]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/4650.jpg?v=1740247384)

In terms of operation, the lack of storage space onboard these ancient ships - for water and food - and the need for relatively calm seas meant that battles were most often fought close to land. In addition, shipwrecked crews could then be more easily rescued.

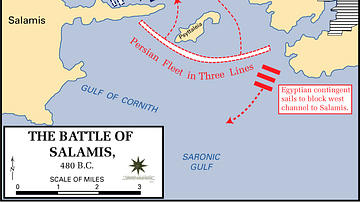

The most celebrated use of triremes in naval warfare, and perhaps the greatest naval battle in ancient history, was fought in 480 BCE at the Battle of Salamis between the Greek navy of the Hellenic League (principally represented by Athens and Corinth) and the invading armada of the Persian king Xerxes I. The victory of Greek navy not only ensured Greece's autonomy but allowed Athens to then take centre stage and make the Athenian trireme an everpresent sight in the Aegean.