The Vandals were a Germanic tribe who are first mentioned in Roman history in the Natural History of Pliny the Elder (77 CE). The Roman historian Tacitus also mentions them in his Germania (c. 98 CE), though he also refers to them as the "Lugi". Their name may mean "the wanderers" and was given by both Pliny and Tacitus as "Vandilii". The name "vandal" has now become synonymous with careless destruction owing to the accounts by Roman writers describing their violent behavior generally and their sack of Rome in 455 CE specifically.

The historian Torsten Cumberland Jacobsen, among others, has observed that this identification of wanton destruction with the Vandals is unfortunate. Jacobsen writes:

Despite the negative connotation their name now carries, the Vandals conducted themselves much better during the sack of Rome than did many other invading barbarians. (52)

Among the many other Germanic tribes, the Vandals were a part of the movement which historians call "The Wandering of the Nations," which took place roughly between 376-476 CE (though this is generally thought to have begun earlier and lasted later), in which large-scale migrations took place (often due to incursions by the Huns), bringing Germanic tribes into closer contact with the Roman Empire and other cultures.

The Vandals breached the Roman frontier in c. 270 CE and became a part of Rome's history from that point on until the Battle of Tricamarum in North Africa in 534 CE, in which the Vandal king Gelimer (r. 530-534 CE) was defeated by the Roman general Belisarius (l. 505-565 CE) and, after this, the Vandals ceased to exist as a cohesive entity.

Early History

The Vandals are believed to have originated in Scandinavia and migrated to the region of Silesia c. 130 BCE. They have been identified with the Iron Age Przeworsk Culture of Poland, though, like the early identification of the Goths with the Wielbark Culture of Poland, this has been contested. Jacobsen, in his work, A History of the Vandals, writes:

To attempt to trace the origin of the Vandals, we must combine archeological and historical sources, which are shaky and contradictory at best. The difficult and scanty sources mean that each statement about the early history of the Vandals should be preceded with, "We believe that possibly...," and end with, "...but we have little or no real evidence of it. (3)

It is not even known if "Vandal" was their original name, as Tacitus refers to them as both Vandals and Lugi, and historians are uncertain as to whether the Vandals were a dominant tribe of which the Lugi were a sub-group or if the entire tribe was simply referred to by two names. Whichever the case, it seems clear from Tacitus' work that there were a number of distinct Germanic tribes who called "Vandals" by the Roman writers. At some point, the tribe divided into separate units (or may have been separate all along and only decided to part ways), and two of these tribes, the Silingi and the Hasdingi, migrated south.

The Silingi Vandals did not go far and remained in Silesia (roughly modern Poland), while the Hasdingi inhabited the region of the Sudeten mountain range. The Hasdingi were invited into Dacia by the Romans as allies during the Marcommanic Wars of 166-180 CE but, during and after the conflict, they seem to have caused more problems for Rome than provide assistance.

The "difficult and scanty sources" Jacobsen writes about come into play here as, according to The History by Peter the Patrician, the Vandals were the allies of Marcus Aurelius while, according to Eutropius, they were his adversaries. The historian Cassius Dio (l. 155-235 CE) reports that they were neither but were simply farmers and federates of Rome who, in 171 CE, were allowed to live in Dacia under the rule of their kings Raus and Raptus. While it therefore remains unclear exactly what their relationship with Rome was early on, they gradually engaged in hostilities with Rome.

War With Rome

By 270 CE they were making regular incursions into Roman territories and, in 271 CE, were beaten back and defeated by the emperor Aurelian (r. 270-275 CE). Prior to this, however, they had been Rome's allies and, like the Goths, served in the military. Aurelian pushed them back across the Danube. In his History of the Goths, Jordanes writes:

At that time they dwelt in the land where the Gepidae now live, near the rivers Marisia, Miliare, Gilpil, and the Grisia, which exceeds in size all previously mentioned. They then had on the east the Goths, on the west the Marcommani, on the north the Hermunduli and on the south the Hister, which is also called the Danube. At the time when the Vandals were dwelling in this region, war was begun against them by Geberich, king of the Goths, on the shore of the river Marisia which I have mentioned. Here the battle raged for a little while on equal terms. But soon Visimar himself, the king of the Vandals, was overthrown, together with the greater part of his people. When Geberich, the famous leader of the Goths, had conquered and spoiled the Vandals, he returned to his own place whence he had come. Then the remnant of the Vandals who had escaped, collecting a band of their unwarlike folk, left their ill-fated country and asked the Emperor Constantine for Pannonia. Here they made their home for about sixty years and obeyed the commands of the emperors like subjects. (83-84)

The Vandals were primarily farmers who laid out their lands, usually in river valleys, so as to form a circular village. They made a living from tending crops and raising animals for slaughter and also through trade. Jacobsen writes, "The houses were one or two rooms, with walls of wood, or wicker covered by clay...The Vandals were also craftsmen. Among the crafts, weapon smithing was highly respected" (6). They were also skilled in making jewelry, in ceramics, and in weaving. They were ruled by a king (or two kings who probably wielded equal power) and seem to have had an upper class of nobility. Jacobsen notes that they were famous for their skill in horsemanship and that "an important role was tending horses for warfare" (6).

The Vandals are described by the ancient sources as tall, blonde, and good-looking and, though mention is certainly made of their domestic life and social structure, the main emphasis is often on their brutality in waging war. The Roman emperor Probus (r. 276-282 CE) defeated them twice in 277/278 CE and killed many either because they would not behave according to the peace treaty or because they would not stop fighting. Those who survived, and submitted, were incorporated into the Roman army and sent to Roman Britain.

Constantine the Great (r. 324-337 CE) secured the Vandals in Pannonia in 330 CE, and they co-existed with their Roman neighbors except in terms of religion. The Vandals were Arian Christians, while the Romans were Trinitarian (or Nicean) Christians. Religious differences caused problems between the Vandals and the Romans, but these were forgotten, temporarily, in the invasion of the region by the Huns.

In 376 CE, when the Goths under Fritigern (d. 380 CE) were fleeing from the Huns, they were allowed entrance into the empire and, of course, those Roman citizens living in Pannonia were allowed in as well; the Vandals, and many other tribes, were not. The Hunnic invasions continued until, in 406 CE, there was a large population of barbarian tribes gathered along the Roman border of the far bank of the Rhine River seeking safety within the borders of the empire. The Roman general Stilicho (l. 359-408 CE) had reduced the garrison guarding the border because he needed as many men as he could muster to fight off Alaric I (r. 395-410 CE) and his Gothic army.

One winter night in 406 CE, the Vandals crossed the frozen river and poured into the empire. They ravaged Gaul and proceeded on to Hispania, settling their people in both regions. Hostilities between the Vandals, the Franks, the Romans, and other tribes continued until c. 420 CE, when the Vandals captured many of the most important ports in Hispania and were able to build a navy to defend them from Rome.

At this time Gunderic (l. 379-428 CE) was king of both the Vandals and the Alans and was able to effectively keep the Romans at bay. He was less successful, however, against the Visigoths of Hispania who already inhabited the region when the Vandals arrived. Gunderic died in 428 CE and was succeeded by his half brother, Gaiseric (r. 428-478 CE, also known as Genseric), who would become the greatest Vandal king and one of the most effective monarchs of the ancient world.

The Reign of Gaiseric

While the Vandals were consolidating their power in Spain and fighting off the Visigoths, the Roman Empire was suffering its usual problems with court intrigue. The emperor in the west was Valentinian III (r. 425-455 CE), who was only a child, and actual power lay with his mother, Galla Placidia (l. 392-450 CE) and the general Flavius Aetius (l. 391-454 CE). Romans generally favored either Aetius or Galla, and the two were almost constantly at work trying to devise plans to thwart the hopes of the other.

In c. 428 CE, Aetius devised a scheme whereby a rival of his, Boniface (who ruled in North Africa, d. 432 CE), was charged with treason against Valentinian III and Galla Placidia. Aetius requested that Galla send for Boniface to come from North Africa and answer the charges while, at the same time, sending word to Boniface that Galla was planning to execute him when he arrived. When Boniface sent word to Galla that he would not come, Aetius declared this was proof of his treason.

At this point, the historian Procopius claims, Boniface invited the Vandals of Spain to North Africa as allies against a Roman invasion. Boniface, as Galla would soon recognize, was innocent of the charges and, as he controlled six provinces in North Africa and the military might to defend them, would have had no need for an agreement with the Vandals. Still, as Aetius and Galla were formidable enemies, Boniface could have sent the invitation to Gaiseric in order to muster as many men as he could.

Another account of the Vandals' invasion of North Africa suggests that Gaiseric had been injured in a fall from a horse and was lame and so decided to henceforth wage war by sea, which led him to invade in order to establish a naval base at Carthage. Historians have argued for and against both of these claims and continue to do so. Most likely, Gaiseric simply wanted a homeland for his people that was rich in resources and free of Visigoths and so took advantage of the confused situation of the Romans and invaded when he felt Boniface could do nothing about it (or, simply accepted Boniface's invitation with a plan in mind to take the province). North Africa was the major grain supplier for the Roman Empire, and if Gaiseric controlled it, he would be able to effectively negotiate with the Romans to his advantage.

Whatever his reasons, Gaiseric led 80,000 of his people from Spain to North Africa in 429 CE. Historians continue to debate whether the number was 80,000 or 20,000, but scholar Walter A. Goffart (following earlier historians) notes:

That Geiseric led 80,000 Vandals and associated peoples from Spain to Africa in 429 has been called the one piece of certain information we have about the size of barbarian groups in the age of the invasions. The certainty arises from its being vouched for by apparently independent informants, one Latin, the other Greek. (231)

Once in Africa, if the claim that Boniface invited him is accepted, he turned on his host and led his forces against the imperial army. He took the city of Hippo (where St. Augustine was bishop at the time) after a siege of fourteen months and, a few years after this, took Carthage. He continued on with a string of victories, conquering cities until he was master of North Africa and the Vandals had their own homeland, much to the dismay of Rome. Scholar Roger Collins writes, "The determination to regain Africa dominated western imperial policy for the next fifteen years" (90). The Romans would be unsuccessful in this, however, until after Gaiseric's death.

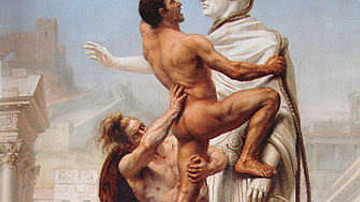

The Sack of Rome

From their port at Carthage, the Vandals now launched their fleet at will and controlled the Mediterranean Sea, which formerly had been Rome's. Gaiseric's navy plundered whatever ships crossed its path and raided coastlines. Plans and attempts by the Romans to drive Gaiseric and his people from North Africa came to nothing, and so, in 442 CE, the Romans acknowledged the Vandal kingdom as a legitimate political entity and a treaty was signed between Gaiseric and Valentinian III.

In 455 CE, Valentinian assassinated Aetius and was then murdered shortly afterwards by Petronius Maximus. Gaiseric claimed that this nullified the treaty of 442 CE, which had been only valid between himself and Valentinian. He sailed for Italy with his fleet, landed unopposed at Ostia, and marched on Rome. The Romans recognized that their military force was inadequate to meet the Vandals and so put their trust in the diplomatic skills of Pope Leo I (served 440-461 CE) and sent him out to meet Gaiseric and plead for mercy.

Leo told Gaiseric he was free to plunder the city but asked him not to destroy it nor harm the inhabitants - and Gaiseric agreed. This was greatly to Gaiseric's advantage on many points, but mainly because Italy was suffering a famine and, when he landed at Ostia, Gaiseric recognized that his army would be unable to affect a prolonged siege of the city because they would have nothing to eat and Rome's walls were formidable. His assent to Leo's request, then, was more an act of expediency and prudence than mercy.

Anything of value, from personal treasures to ornaments on buildings and statues, was taken by the Vandals, but they did not destroy the city and few people were harmed other than Petronius Maximus, who was killed by a Roman mob when he tried to flee and was caught outside the walls. The Vandals looted the city and then marched back to their ships and sailed home, taking with them a number of high-profile hostages including Valentinian III's widow and her daughters. Collins writes:

The sack of Rome of 455 had the immediate effect of making the Vandal threat to Italy seem far more menacing than [other threats]. Despite the Vandals immediately returning to Africa with their loot, the whole episode brought home in a day that seems not to have been previously appreciated just how vulnerable Italy, and Rome in particular, was to sea-borne raiding. (88)

Realizing they could no longer afford to tolerate the Vandals in North Africa, the Romans gathered their strength and launched an attack in 460 CE. Gaiseric, who was always vigilant of Roman military movements, launched a pre-emptive strike and destroyed or captured most of the Roman fleet. In 468 CE the eastern and western halves of the empire united against the Vandals and sent the whole of their fleet against them. Gaiseric surprised the Romans and defeated them, destroying 600 of their ships and capturing others. Rome was forced to ask for peace, and Ricimer, who effectively ruled the Western Roman Empire at this point, had to accept Gaiseric's terms, which were simply a restatement of the treaty of 442 CE, allowing the Vandals to do whatever they wanted whenever they pleased.

Gaiseric's Death & Conflict with Rome

Gaiseric died peacefully of natural causes in 478 CE. As long as he had ruled, the Vandals were secure but, after his death, the Vandal kingdom began to decline. He was succeeded by his son Huneric (r. 478-484 CE), who spent more time and energy persecuting the Trinitarian Christians in his realm than doing anything else. When he died in 484 CE, he was succeeded by his nephew Gunthamund (r. 484-496 CE), who ended the persecutions of Trinitarians by Arian Christians and recalled the Catholic bishops and clergy who had gone into exile. Gunthamund died in 496 CE and was succeeded by Thrasamund (r. 496-523 CE), who ruled effectively until 523 CE when he died and was succeeded by Huneric's son Hilderic (r. 523-530 CE).

Gaiseric had organized a system of succession whereby the oldest male of a family would ascend to rule on the death of the king. He hoped that this would prevent succession problems, which it did, but it also guaranteed that kings would be taking the throne at more and more advanced ages. Hilderic was in his mid-sixties when he became king, and those who followed him were in the same age range. The historian Guy Halsall writes, "The age of the later Vandal kings doubtless explains their lack of vigour in dealing with the problems that beset their realm" (295).

The Moors rose against the Vandal kingdoms of the north and defeated Hilderic's forces at some point toward the end of his reign (the date is not known). Thrasamund's nephew, Gelimer, grew tired of Hilderic's inept handling of the kingdom and had him imprisoned, along with his family, following this defeat by the Moors. It was not only Hilderic's lack of military skill which bothered Gelimer, however, but his adoption of Trinitarian Christianity. Gelimer, like Gaiseric and the majority of the Vandals, was an Arian Christian. Gelimer took the throne and began reinstating the persecutions of Trinitarian Christians from Huneric's time.

His anti-Trinitarian policies angered the Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE), who sent him a harshly worded letter requesting that he stop the persecutions immediately and protesting the treatment of Hilderic. Gelimer replied that "nothing was more desirable than that a monarch should mind his own business" and continued to rule as he pleased. Justinian, who was a devout Trinitarian and enemy of the Arian belief, saw in Gelimer's reply an excuse to invade North Africa and finally drive the Vandals out: he would mount a crusade, of sorts, to save the Trinitarians in North Africa from Gelimer's persecutions (though this claim is disputed and some scholars note that Justinian I only wanted to recapture lost Roman ports on the coast). Historian J.F.C. Fuller writes:

An insatiable worker and centralizer, Justinian was called "the emperor who never sleeps". He looked upon himself not only as heir of the Caesars, but also as the supreme head of the Church, and throughout his reign he held two fixed ideas: the one was the restoration of the Western Empire, and the other the suppression of the Arian heresy. Hence all his western wars took on the character of crusades, for he felt that his mission was to lead the heathen peoples into the Christian fold...A good judge of men, he selected Belisarius, a young officer of his body-guard, to command the Eastern Army. (307)

The Final Battle with Rome

Belisarius landed in North Africa with a fleet of 500 ships, 20,000 sailors, 10,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry, and 92 smaller warships rowed by 2,000 slaves. Gelimer, meanwhile, was unaware that the army had even left Constantinople. When he heard the Byzantine army was ten miles from Carthage, at the defile of Ad Decium, he had Hilderic and his family, and any of Hilderic's friends and supporters he could find, executed so the former king could not be restored to the throne. Gelimer then decided upon a three-pronged attack which would destroy the invading army. Fuller writes:

Gelimer's plan of operations was an over-complicated one: he decided, once his enemy had entered the Ad Decium defile, to launch a combined attack on him from three directions. While [his brother] Ammatus sallied forth from Carthage and engaged the Byzantine van, he himself with the main body was to fall upon the rear of the enemy's main body, and at the same time his nephew, Gibamund, was to move over the hills from the west and to attack the enemy's left flank. Procopius expresses his astonishment that Belisarius's army should have escaped destruction. But, because correct timing was the prerequisite of success, in a clockless age it would have been a fluke had the three columns engaged simultaneously. (312)

Ammatus struck before the other two forces were in position and was killed. After he fell, his troops fled in a panic and were cut down by the Byzantine army. Gibamund then attacked the left flank and was quickly routed by Belisarius' Hun cavalry. Gelimer arrived late and completely missed the enemy's rear, finding only the body-strewn battlefield and his dead brother. His forces still far outnumbered those of Belisarius, however, and if he had gone in pursuit of the Byzantines at that moment, he may have won the war. As it was, however, he was so distraught over the death of Ammatus that he refused to move his army forward until he had given him a proper burial with all rites. This delay allowed Belisarius to reach Carthage and take it without effort.

Gelimer marched on Carthage with an enormous army and lay siege. They destroyed the aqueduct and cut off the water supply to the city, and so Belisarius, though vastly outnumbered, felt he had no choice but to march out and meet Gelimer's forces in the field. They met at Tricameron, in December 533 CE, and Belisarius was careful in the placement of his troops to conceal his fewer numbers. He ordered the battle to commence with a cavalry charge, which broke the Vandal lines and scattered them in an hour.

As the cavalry cut down the fleeing Vandals, Belisarius moved his infantry up, and Gelimer, according to Procopius, looked upon the Byzantine forces marching toward him and "without saying a word or giving a command, leaped upon his horse and was off in flight on the road leading to Numidia" (IV.iii. 20). As their king fled the field, the Vandal army erupted in panic, broke ranks, and tried to save themselves however they could.

When the Byzantine army reached the Vandal camp, it was deserted, and they broke ranks and began to plunder it. Procopius observes that, had Gelimer only given the matter some thought, "or had an ounce of courage", he would have simply withdrawn his army beyond the camp, left it as bait for the enemy, and "once they had fallen upon it he would have fallen upon them and regained his camp and his kingdom." This is the tactic that Belisarius feared Gelimer was, in fact, employing and tried to organize his men in case a surprise attack came in the night. No attack came, however, and the next day Belisarius sent his men in pursuit of Gelimer, who was finally caught in March 534 CE and brought back in chains to Constantinople as part of Belisarius' triumph.

The End of the Vandals

The Vandal kingdom of North Africa had fallen and, with it, the Vandals were dispersed. Many Romans had married Vandal women and brought them back to Constantinople, many other Vandals were killed in the battles of Ad Decium and Tricameron, and still others were killed by the Moors. The conflicts between the Trinitarian Christians and the Arian Christians flared again after Gelimer's defeat and Belisarius' return to Constantinople, and with no firm government in place, the two groups killed each other until the Moors, seeing an opportunity, attacked from the south and destroyed great swaths of the population.

Justinian had defeated the Vandals and brought North Africa back into the Roman fold but, as Fuller observes, "five millions of Africans were consumed by the wars and government of the emperor Justinian" (316). Those Vandals who survived continued to live under Roman rule in North Africa or migrated to Europe but never formed a cohesive ethnic group again.