The Visigoths were the western tribe of the Goths (a Germanic people) who settled west of the Black Sea sometime in the 3rd century CE. According to the scholar Herwig Wolfram, the Roman writer Cassiodorus (c. 485-585 CE) coined the term Visigothi to mean 'Western Goths' as he understood the term Ostrogothi to mean 'Eastern Goths'. Cassiodorus was simply trying to coin a name to differentiate the two extant tribes of the Gothic people in his time who clearly differed from each other; these tribes did not originally refer to themselves by these names. The Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus (4th century CE) refers to the Visigoths as the Tervingi (also given as Thervingi), which may have been their original name. The designation Visigothi seems to have appealed to the Visigoths themselves, however, and in time they came to apply it to themselves.

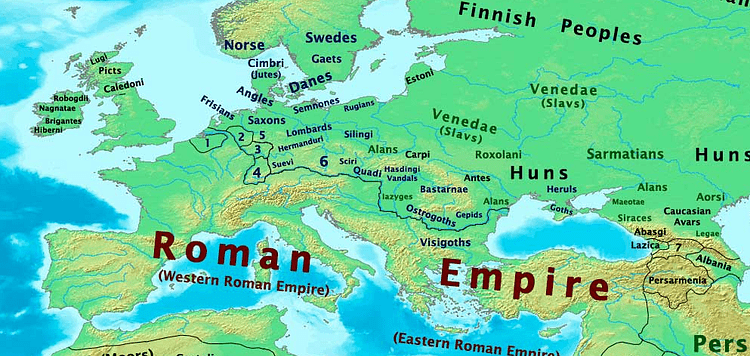

The Visigoths would eventually settle in the region of modern-day Germany and Hungary until they were driven out by the invading Huns. Some Visigoths, under their general Fritigern (d. c. 380 CE) were granted land by the emperor Valens (r. 364-378 CE) in Roman territory. Their mistreatment at the hands of Roman provincial governors would lead to the First Gothic War and the pivotal Battle of Adrianople (378 CE) in which Rome was defeated by the Goths under Fritigern. The Visigoths would further impact Rome when their king Alaric I (r. 395-410 CE) sacked the city in 410 CE. After Alaric I, the Visigoths migrated to Spain where they established themselves and assimilated with the Romans and indigenous people living there.

Origin & Identity

The Goths probably came from the region of modern-day Gdansk, Poland (though this claim is contested), before migrating toward the boundaries of Rome. The scholar Walter Goffart argues that there can be no “history of the Goths” before their appearance in Roman texts because prior to this time (c. 238 CE) there was no written history (8). The primary source on Gothic history is Jordanes' Getica (6th century CE) which draws on Cassiodorus' work as its primary source and weaves mythological and legendary events in with the historical narrative. Goffart, therefore (among others), claims that the Roman history of the Goths is the only history.

Other scholars (Peter Heather among them), claim that Gothic identity, history, and place of origin – Gdansk – can be traced using Jordanes' work coupled with archaeological evidence. Heather contends that just because there are mythological elements in Jordanes' Getica is no reason to reject the entirety of the work, especially since physical evidence (such as 3,000 Gothic tombs discovered in Eastern Pomerania, Poland, in 1873 CE) supports Poland as point of origin or, at least, the early starting point for the later Goth migrations.

Heather further argues that 'Goth' does not have to be understood as a uniform ethnic group which remained unchanged through time. In Heather's view, Germanic tribes which were not ethnically 'Goth' could still have been included in the tribe which came to be known as the Visigoths. Heather claims:

There is no reason to suppose that Gothicness will have been expressed by the same means in every period where our sources report the existence of Goths. We do not have to find unchanging cultural constants to prove the existence of Goths as a historically continuous entity…it is the reaction of individual consciousness to [certain] peculiarities, not the items themselves, that are important. Identity is an internal attitude of mind which may express itself through objects, norms, or particular ways of doing things…most of those recruited to create the Visigoths would seem to have been Goths from pre-existing, pre-Hunnic Gothic groups and the Visigoths were certainly not exclusively Gothic. (65)

In Heather's view (which follows the work of Herwig Wolfram on this), the Visigoths should be viewed as more of a confederation of Germanic tribes than a homogeneous ethnic group. Heather notes:

Wolfram, in particular, argued that Gothic groups of the Migration Period might better be viewed as armies than peoples, and that anyone who fought with the army could become a Goth, whatever their actual biological origins. (44)

Other scholars, including Goffart and Michael Kulikowski, regard the Goths as an ethnic group whose origins are unknown and unknowable. They reject the claims regarding a known point of origin and clear development of a Gothic history on the basis that Jordanes is unreliable, the physical evidence supporting Gdansk as point of origin has been interpreted in light of Jordanes' narrative, and that scholars like Heather are still relying on Roman narratives to construct a pre-Roman history of the Goths in general and the Visigoths in particular.

As noted, there is no written history of the Goths prior to the Roman historians. The Goths are first mentioned in the work of the Roman writer Pliny the Elder (l. 23-79 CE) in 75 CE, but they are given a much fuller treatment by Tacitus (l. c. 56-120 CE) in his Germania (98 CE). Tacitus characterizes them as fierce Germanic warriors, highly superstitious and completely barbaric, but fiercely loyal to their families and tribes (Germania, 17). In 238 CE, the Goths invaded Roman territories and in 251 CE, under the leadership of their general Cniva (r. c. 250-270 CE), they defeated the Roman army under the emperor Decius (r. 249-251 CE), killing him and his son at the Battle of Abritus. After this time, the Goths consistently appear in the works of Roman historians.

The Gothic Civil War

Wherever they came from, by the 3rd century CE the Goths were in proximity to Roman territories and interacting with Roman citizens. The Visigoths, at least in part, seem to have resisted Roman influence on their culture at the same time they courted Roman employment. Goths served as mercenaries in the Roman army during the Roman-Persian Wars, participating in the Battle of Misiche in 244 CE, among others, even though Goths had previously fought against Rome.

This paradigm would continue as one group of Visigoths, under a certain leader, would vigorously oppose Rome while another would court Rome's favor and friendship. The Visigoth king Athanaric (d. c. 381 CE) was especially opposed to the new “Roman” religion of Christianity which he saw as a Roman construct and a threat to Gothic culture and tradition. When the Gothic Christian missionary Ulfilas (l. c. 311-383 CE) began converting Goths to the new faith, Athanaric persecuted the converts severely. Athanaric was actually right in his suspicions since Rome did believe Christianity could be a 'civilizing' influence on the Goths which would essentially Romanize them and neutralize them as a threat.

While Athanaric stood firm against Rome, Fritigern sought alliance and cooperation. This could be because Fritigern had already converted to Christianity and so felt more in common with the Romans, but this is speculation since the date of Fritigern's conversion is unknown. Although there were other factors involved, the split between pagan and Christian Goths came to a head in the Gothic Civil War between Athanaric and Fritigern. Fritigern was an Arian Christian who opposed Athanaric's persecutions and the two leaders warred on each other.

Athanaric defeated Fritigern and the latter appealed to the Roman emperor Valens for help. Valens was also an Arian Christian and sent troops against Athanaric between 367-369 CE. The Roman army made no real headway, however, because Athanaric's forces relied on guerilla warfare and, knowing their lands well, could attack and disappear without offering the Romans a traditional battlefront.

The Huns & First Gothic War

Athanaric might have emerged as the clear victor of the conflict if not for the arrival of the Huns who destroyed his food supplies and proved a far more formidable enemy than Rome. Using the same tactics Athanaric had used against Rome, the Huns struck without warning and vanished away again before the Goths had a chance to engage them. Athanaric sued for peace with Rome and sought ways to deal with the Huns while Fritigern appealed to Valens for sanctuary in the Roman Empire.

Valens consented and the Visigoths under Fritigern settled in an area near the Danube in 376 CE. Mistreatment by provincial Roman governors soon led to widespread discontent among the Visigoths and, by late 376 CE, open rebellion had broken out. The Visigoths plundered the neighboring Roman towns, growing in power and wealth as they went.

Emperor Valens took the field, marching from Constantinople in the Eastern Roman Empire, in what came to be known as The First Gothic War (376-382 CE). At the Battle of Adrianople in 378 CE the Visigoths won a decisive victory against the forces of Valens (an event which historians mark as the beginning of the end of the Roman Empire) and the emperor himself was killed in the battle. Valens' defeat has been attributed as much to his own pride and rash decisions as Fritigern's skill as a general because Valens refused to wait for reinforcements from the Western Roman Empire, believing he could win a quick and glorious victory.

Visigoths & Rome under Theodosius I

Theodosius I (r. 379-395 CE) of the Western Roman Empire then became emperor also of the Eastern Roman Empire and tried to halt the progress of the Visigoths as they then swept on to Thrace. In 382 CE, a peace treaty was concluded between the Visigoths and Theodosius I of Rome although it is unclear who represented the Gothic interests in this as both Athanaric and Fritigern were dead by this time.

Theodosius I tried to cement the peace by instituting regional Visigoth governors and, more importantly, trying to unite the Visigoths and the Romans through Christianity. Following the policy of earlier emperors like Valens, Theodosius I believed that a common bond of religion provided by Christianity would neutralize any Gothic threat to Rome. The Visigoths who had converted, however, practiced Arian Christianity while Theodosius I, and many of the Romans, followed the Nicene Creed instituted by Constantine the Great at Nicaea in 325 CE. While Theodosius I was not successful in his efforts at religious unification, the peace he brokered lasted until his death in 395 CE.

Alaric I & the Sack of Rome

With his death, the Visigoths in service to Rome received even less consideration than they had under his reign. The Visigoths who had participated in the Battle of Frigidus in 394 CE had essentially been used as fodder in the front lines to preserve Roman troops. Alaric I objected to this treatment of his people and the Visigoths rejected Roman rule and proclaimed Alaric I their king.

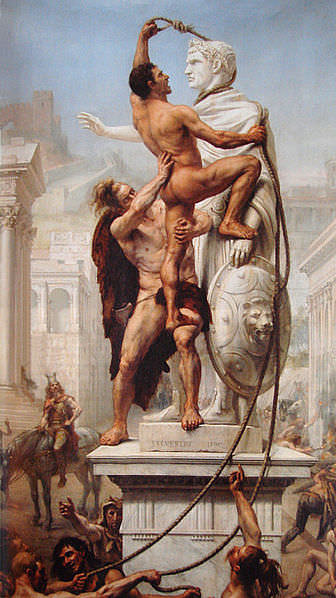

Alaric I tried to unite the Visigoths and Romans by having Visigoth governors introduce Roman customs and culture in their regions. While he was moderately successful, Alaric was better suited as a warrior than an administrator and, in 396 CE, having failed to win the rights he felt were being denied his people, he led his forces through the Balkans, pillaging as they went, down into Greece. He then turned back to Italy and, after a number of engagements with the faltering Roman forces, sacked Rome in 410 CE.

The Visigoths in Spain

Alaric died soon after, and his successor, Athaulf (r. 411-415 CE) led the Visigoths in the conquest of Gaul, establishing the Visigoth Kingdom of Toulouse. Following Athaulf, King Wallia (r. 415-418 CE, who assassinated Athaulf) expanded the kingdom to found the Visigothic Kingdom (c. 418-721 CE). This political entity helped to preserve the cultural legacy of Rome and the classical tradition.

His successor, Theodoric I (r. 418-451 CE), enlarged it even further to include a large part of Spain. Theodoric I was killed at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains in 451 CE as an ally of Rome fending off the invasion of Attila the Hun. Leadership of the Visigoths then went to his son Theodoric II (r. 453-466 CE). The Visigoths were now firmly established in Spain but were at odds with a number of their fellow citizens there.

The Visigoths at this time still practiced Arian Christianity while the inhabitants of Spain were Nicene Christians (recognized today as Catholics). Theodoric II was assassinated by his brother Euric (sometimes referred to as Euric II, r. 466-484 CE). According to some sources, Euric carried out intense persecutions of the Nicene Christians while, according to others, he merely targeted high-ranking church officials whom he deemed problematic. After his death, Alaric II (r. 484-507 CE) became king and, at this time (c. 485 CE) Clovis I of the Franks (r. 509-511 CE) accepted Nicene Christianity and sought to drive the Arian Visigoths from the region as a kind of 'liberation' of the Nicene Christians who had appealed to him for help.

In 507 CE, prior to becoming king, Clovis I marched on the Visigoths to destroy the Arian 'heresy' they were inflicting on the Nicene Christians. Alaric II was defeated in battle by Clovis, dying in the engagement, and the Visigoth kingdom became Frankish. The capital was set up at Toledo and a gradual merging of the cultures began between the Romans and the Visigoths. In 711 CE, the Muslim forces conquered Spain in the ongoing Arab invasion and, in so doing, accelerated the assimilation of the two cultures into one united front against the conquerors. In time, the native Romans of Hispania and the Visigoths became the united culture of Spain.

Conclusion

In 722 CE, at the Battle of Covadonga, the Visigoth nobleman Pelagius of Asturias (l. c. 685-737 CE) defeated the Muslim forces and thus began the Christian reconquest of Spain. In 732 CE, at the Battle of Poitiers (also known as the Battle of Tours) the Frankish King Charles Martel (the Hammer, r. 718-741 CE) defeated the Muslim forces under Rahman to permanently halt Muslim military incursions into Europe. After driving the Muslims out of Galicia in 739 CE, the Roman Catholic Church was established by the new government as the national faith and official religion of the country. The German Visigoths and the Italian Romans had become the unified people of Spain.

One of the greatest legacies of the Visigoths in Spain was the Visigothic Code (also known as the Visigothic Law Code, the Lex Visigothorum, 642-643 CE) enacted by the Visigothic king Chindasuinth (r. 642-653 CE) which ended any differentiation between Roman and Visigoth subjects in Spain and mandated equality before the law for all citizens. These laws equalized the people of Hispania and elevated the rights of women through the provisions concerning family law which ensured the property rights of married women without regard for a male family member's supervision or approval. The Visigoths, from their arrival in Spain onwards, informed Spanish culture which was shared with other nations through trade. Their contributions to world culture are evident in their law code and the preservation of important aspects of Western Civilization in Visigothic Spain.