The word 'war' comes to English from the old High German language word Werran (to confuse or to cause confusion) through the Old English Werre (meaning the same), and is a state of open and usually declared armed conflict between political entities such as sovereign states or between rival political or social factions within the same state.

The Prussian military analyst Carl Von Clausewitz, in his book On War, calls it, “continuation of politics carried on by other means.” War is waged by political entities, nations or, earlier, city states in order to resolve political or territorial disputes and are carried out on the battlefield by armies comprised of soldiers of the contending nations or by mercenaries paid by a government to wage battle.

War & the Rise of Nations

Throughout history, individuals, states, or political factions have gained sovereignty over regions through the use of war. The history of one of the earliest civilizations in the world, that of Mesopotamia, is a chronicle of nearly constant strife. Even after Sargon the Great of Akkad (r. 2334-2279 BCE) unified the region under the Akkadian Empire, war was still waged in putting down rebellions or fending off invaders. The Early Dynastic Period of Egypt (c. 3150-c. 2613 BCE) is thought to have risen from war when the Pharaoh Manes (or Menes) of the south conquered the region of northern Egypt (though this claim is disputed).

In China, the Zhou Dynasty gained ascendancy through battle in 1046 BCE and the conflict of the Warring States Period ((476-221 BCE) was resolved when the State of Qin defeated the other contending states in battle and unified China under the rule of emperor Shi Huangdi (r. 221-210 BCE). This same pattern holds for other nations throughout time whether one cites the success of Scipio Africanus (l. 236-183 BCE) in the defeat of Carthage (and so the ascendancy of Rome) or that of Philip II of Macedon (l.382-336 BCE) in uniting the city-states of Greece. Contending armies of opposing nations have historically settled political disputes on the battlefield even though, in time, these armies changed in formation and size.

Armies & Their Development

Armies contained two types of infantry: Shock Troops, whose purpose was to close with the opposing forces and try to break their lines, and Peltasts who were more mobile and moved in a looser formation in order to fire long-range weapons at the enemy. According to the historian Simon Anglim, et.al., "Infantry is the backbone of any army, being the one unit that can attack or defend equally effectively. The majority of battles have turned on the infantry's ability to close with the enemy and kill him" (7) and this holds true, in most cases, even after the introduction of cavalry units and the war chariot.

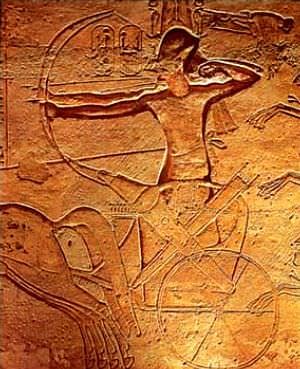

The earliest armies were relatively small corps of shock troops until the introduction of peltast units. At the Battle of Megiddo in 1479 BCE the Egyptian army numbered 20,000; by the time Shalmaneser III ruled over the Assyrian Empire in 845 BCE armies had grown in mass and size. Shalmaneser's forces in his campaigns numbered over 120,000. The Assyrians required large armies owing to their policy of territorial expansion and ruthless suppression of revolt against central rule and, in this, they epitomize the underlying cause of war: the tribe mentality.

The Tribe Mentality & War

War grows naturally out of the tribe mentality. Anglim, et.al., notes:

A tribe is a society tracing its origin back to a single ancestor, who may be a real person, a mythical hero, or even a god: they usually view outsiders as dangerous and conflict against them as normal. The possession of permanent territories to defend or conquer brought the need for large-scale battle in which the losing army would be destroyed, the better to secure the disputed territory. The coming of `civilization' therefore brought the need for organized bodies of shock troops. (8)

The tribe mentality always results in a dichotomy of an `us' vs. a `them' and engenders a latent fear of the `other' whose culture is at odds with, or at least different from, one's own. This fear, coupled with a desire to expand, or protect, necessary resources, often results in war.

The first war in recorded history took place in Mesopotamia in c. 2700 BCE between Sumer and Elam. The Sumerians, under command of the King of Kish, Enembaragesi, defeated the Elamites in this war and, it is recorded, “carried away as spoils the weapons of Elam.” At approximately the same time as this campaign, King Gilgamesh of Uruk marched on his neighbors in order to procure cedar for construction of a temple. While it has been argued that Gilgamesh is a mythological character, the archaeological evidence of the historical King Enembaragesi, who is mentioned in The Epic of Gilgamesh, lends weight to the claim that the latter was also a real historical figure. The region of Sumer traditionally looked upon Elam as `the other' to the point where, in the Ur III Period of Sumer's history (2047-1750 BCE) King Shulgi of Ur (r. 2029-1982 BCE) constructed a great wall to keep the Elamites and Amorites at bay.

Early Warfare & Military Tactics

Warfare certainly did not begin in 2700 BCE, however. The earliest pictographs of armies at war come from the kingdom of Kish, dated to about 3500 BCE. Jericho, which, along with Uruk, has a claim to the title of the world's oldest city, has provided archaeologists with solid evidence that a fortified city stood on the site before 7000 BCE. The walls of the fortress were 10 feet (3 metres) thick and 13 feet (3.9 metres) high surrounded by a moat 30 feet (9.1 metres) wide and 10 feet (3 metres) deep, strongly suggesting the importance of defense.

The simple bow was in use in Mesopotamia as early as 10,000 BCE and cemeteries from northern Mesopotamia to Egypt attest to early warfare on a fairly significant scale. Evidence from a conflict which took place at Jebel Sahaba, Egypt, at the so-called Site 117, 59 skeletons were uncovered, all of whom show clear evidence of violent death at about the same time. War in ancient Mesopotamia was waged by infantry shock troops until the introduction of the composite bow from Egypt.

By 1782 BCE, Lower Egypt had been largely taken by the Hyksos, a Semitic people of unknown origin, who introduced superior technological advances into Egypt. Along with the war chariot, bronze weapons, and new tactics, the Hyksos brought the advance of the composite bow. Prior to the coming of the Hyksos, the Egyptian army had used "simple bows of wood or cane with a range of around 33 feet (100 metres) while the composite bow was "capable of delivering a mighty blow out to 656 feet (200 metres)" (Anglim, et.al. 10). The development of the composite bow would change the way in which war was waged in that shock troops who were massed closely together made easy targets for archers while looser formations invited decimation by opposing shock troops. This led to changes in battle formations generally and the development of military tactics.

Military Formations & Technology

The earliest formation was the phalanx which was first employed in Sumer c. 3000 BCE and would become the standard for infantry formations for thousands of years. It was made famous at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE when the Greeks employed it effectively to rout the Persians, was perfected by Alexander the Great c. 332 BCE on his campaigns, and was made more formidable by the armies of Rome. The phalanx was employed, in one form or another, by most of the fighting forces in the ancient world. The Greeks employed cavalry to protect the flanks and the Thebans used a combination of cavalry, infantry, and peltasts. The introduction of the war chariot and, later, the use of elephants in battle, supplemented the role of the infantry but never diminished their importance.

War has been an important factor in creating states and empires throughout history and, equally so, in destroying them. Major advances in science, technology, and engineering have been brought about through necessity during times of war. It is written that the army of King Croesus of Lydia (r. 560-547 BCE) was once stopped in their advance by the Halys River which seemed impossible to cross. The philosopher Thales of Miletus, a member of Croesus' army, had a crew of engineers dig a channel upstream, giving it a crescent shape, “so that it should flow round the back of where the army was encamped, being diverted in this way from its old course and passing the camp, should flow into its old course once more" (Kaufmann, 9). Once the river was made shallow in both channels it was, of course, easy to cross.

Stories such as this provide examples of the importance of engineers in the practice of war. The increasing development of military tactics or, in this case, geographical obstacles, necessitated a corps of engineers as a regular part of any army. The armies of Alexander the Great and of Rome are well known for their use of engineers in warfare most notably by Alexander at the Siege of Tyre (332 BCE) and by Julius Caesar at the Siege of Alesia (52 BCE). Both of these generals took full advantage of every resource at their disposal to crush their enemy and advance their cause and engineers, along with technological advances such as the siege tower, became a particularly important means to achieving those ends.

Armageddon

With advancements in technology, war has increasingly wreaked chaos and destruction upon the lives and cities of combatants and non-combatants and, true to the origins of the name, has sown confusion throughout time. The first armed conflict in history recorded by eyewitnesses was the Battle of Megiddo in 1479 BCE between Thutmose III (r. 1458-1425 BCE) of Egypt and an alliance of former Egyptian territories under the leadership of the King of Kadesh.

The Hebrew name for Megiddo is `Armageddon' well known from the biblical Book of Revelation as the site of the final battle between good and evil and has come to be used as a general term for a dramatic situation involving the end of the world. If one regards the predictions of Revelation as trustworthy then, as the historian Davis notes, "The foundation for one of the great ironies of history is thus foretold: the beginning and the end of military history occur at the same site" (5). However that may be, war continues as a common extension of political disputes in modern times and, as human beings never radically change in disposition, will continue be employed in the future as it has been in the past; fueled and justified by the ages-old tribe mentality.