Zenobia (b. c. 240 CE, death date unknown) was the queen of the Palmyrene Empire who challenged the authority of Rome during the latter part of the period of Roman history known as The Crisis of the Third Century (235-284 CE also known as The Imperial Crisis), defined by constant civil war allowing for break-away regions to form governments.

The crisis has been noted by historians for widespread social unrest, economic instability and, most significantly, the dissolution of the empire, which broke into three separate regions: the Gallic Empire, the Roman Empire, and the Palmyrene Empire. The chaos of the central government was such that any attempts to control the outer regions were considered secondary and so, for a time, the empire split into three distinct political entities, including Zenobia's.

Contrary to popular assertions, Zenobia never led a revolt against Rome, may never have been paraded through Rome's streets in chains, and was almost certainly not executed by the emperor Aurelian (r. 270-275 CE). Ancient sources on her life and reign are the historian Zosimus (l. c. 490 CE), the Historia Augusta (c. 4th century CE), the historian Zonaras (l. 12th century CE), and historian Al-Tabari (l. 839-923 CE) whose account follows that of Adi ibn Zayd (l. 6th century CE) although she is also mentioned in the Talmud and by other writers.

While all of these sources maintain that Queen Zenobia of Palmyra challenged the authority of Rome, none of them characterize her actions as an outright rebellion. This view of her reign, of course, depends on one's definition of "rebellion". While she was careful not to engage Rome directly in military conflict, it is clear she increasingly disregarded Roman authority in establishing herself as the legitimate monarch of the east.

Early Life & Marriage

Zenobia was born in Palmyra, Syria sometime around 240 CE and given the name Julia Aurelia Zenobia. Syria was at this time a Roman province and had been since it was annexed in 115/116 CE. Zenobia was a Roman citizen, as her father's family had been granted that status earlier, probably during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180 CE). The Historia Augusta claims that her father could trace his lineage to the famous Julia Domna (l. 170-217 CE) of the Severen Dynasty of Rome.

Zenobia was educated in Greek and Latin, though may have had difficulty with them, but was fluent in Egyptian and Aramaic, and claimed ancestry from the legendary Dido of Carthage and Cleopatra VII of Egypt. According to the Arabic version of her story told by Al-Tabari, she was placed in charge of the family flocks and shepherds when she was a young girl and thereby grew used to ruling over men.

Al-Tabari also claims that this is when she became adept at riding horses and learned the endurance and stamina she was later known for. It is recorded she would march on foot with her troops long distances, could hunt as well as any man, and could out-drink anyone. The historian Edward Gibbon describes the queen in a passage from his famous work:

Zenobia is perhaps the only female whose superior genius broke through the servile indolence imposed on her sex by the climate and manners of Asia. She claimed her descent from the Macedonian king of Egypt, equalled in beauty her ancestor Cleopatra, and far surpassed that princess in chastity and valour. Zenobia was esteemed the most lovely as well as the most heroic of her sex. She was of a dark complexion. Her teeth were of a pearly whiteness, and her large black eyes sparkled with uncommon fire, tempered by the most attractive sweetness. Her voice was strong and harmonious. Her manly understanding was strengthened and adorned by study. She was not ignorant of the Latin tongue, but possessed in equal perfection the Greek, the Syriac, and the Egyptian languages. She had drawn up for her own use an epitome of oriental history, and familiarly compared the beauties of Homer and Plato under the tuition of the sublime Longinus. (128-129)

The passage is given here at length because, firstly, it is largely drawn from the description of Zenobia in the Historia Augusta, and secondly, because Gibbon's work would have a significant impact on how later generations understood the Queen of Palmyra. In both, she is presented as a woman of impressive abilities, and this is how ancient readers and later generations came to regard her.

Even the Arabian sources, in which she is less heroic and more conniving, represent her as a notable queen. In addition to the other virtues which are repeated in the ancient sources, special mention is always made of her chastity. She believed that sex should only be engaged in for the purposes of procreation and, after her marriage, refused to sleep with her husband except for that purpose.

By 258 CE, Zenobia was married to Lucius Septimus Odaenathus, the Roman governor of Syria, with whom she had at least one son, Vaballathus. She was Odaenathus' second wife, and he had a son and heir, Herodes, from his first marriage. Odaenathus ruled over a very prosperous region and especially the city of Palmyra, which was an important trade center on the Silk Road between the east and the west. Merchants coming to or returning from Rome had to stop in Palmyra to pay taxes and simply to rest.

Since around the year 227 CE, however, trade had been halted at intervals by the Sassanid Persians who periodically blocked the route to exact tribute. Silk had been among the most popular commodities in Rome from before the time of Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE), and the Romans were not pleased with these disruptions in trade. The Sassanid king Shapur I (r. 240-270/272 CE) took the city of Antioch, one of the most important trade centers for Rome, and this could not be tolerated.

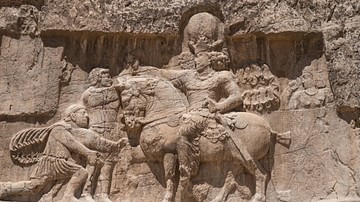

In 260 CE the Roman emperor Valerian (r. 253-260 CE) marched against the Sassanids, was defeated by them, and taken prisoner. Allegedly he was then used as a footstool by Shapur I to mount his horse until he died in captivity and was then stuffed and put on display. His son, Gallienius, could do nothing to remedy the situation, and so Odaenathus marched against the Sassanids, defeated them, and drove them back across the Euphrates River and away from Syria. Although Odaenathus presented himself as acting in Rome's interests to try to save Valerian, he actually had other motives: he had tried to form an alliance with Shapur I, was rebuffed, and only then became his enemy.

For his service to Rome, Odaenathus was made governor of the entire eastern part of the Roman Empire. In 261 CE, when the usurper Quietus challenged Gallienius' rule, Odaenathus defeated and killed him and, after this, had enough power and prestige to effectively rule over his realm almost independent of Rome. In 266/267 CE he was assassinated, along with his son Herodes, by his nephew after a dispute following a hunting trip. While some sources have claimed, or at least suggested, that Zenobia had him murdered so that her son could become king, this has been rejected by most later writers and historians.

Rise to Power & Conquest of Egypt

Zenobia then became regent, since Vaballathus was still a minor. She surrounded herself at court with intellectuals and philosophers, among them the Platonist Cassius Longinus (l. 213-273 CE) who would later be blamed for encouraging her break with Rome. Thus far, the relationship between Palmyra and Rome had been amicable because Odaenathus' military actions had been just as much in Rome's favor as in his own.

When Zenobia came to power, she maintained her late husband's policies. In the chaos of Rome which characterized the Crisis of the Third Century, 26 men had come and gone as emperor. Odaenathus may have thought that he could be next by proving himself of value to Gallienus and by amassing his own wealth by plundering the cities of the Sassanids. After his death, Zenobia may have considered that her son, or even she herself, could rule Rome and so continued her husband's reign as he had conducted it. The historian Richard Stoneman writes:

During the five years after the death of Odaenathus in 267 CE, Zenobia had established herself in the minds of her people as mistress of the East. Housed in a palace that was just one of the many splendors of one of the most magnificent cities of the East, surrounded by a court of philosophers and writers, waited on by aged eunuchs, and clad in the finest silk brocades that Antioch or Damascus could supply, she inherited also both the reputation of Odaenathus' military successes and the reality of the highly effective Bedouin soldiers. With both might and influence on her side, she embarked on one of the most remarkable challenges to the sovereignty of Rome that had been seen even in that turbulent century. Rome, afflicted now by invasion from the barbarian north, had no strong man in the East to protect it...Syria was temporarily out of mind. (155)

Gallienus was assassinated in 268 CE and replaced by Claudius II who then died from fever and was succeeded by Quintillus in 270 CE. Throughout this time, Zenobia's policies steadily changed and, in 269 CE, seeing that Rome was too busy with its own problems to notice her, she sent her general Zabdas at the head of her army into Roman Egypt and claimed it as her own.

Even in this, however, she was careful not to appear to be in conflict with Rome. A Syrian-Egyptian by the name of Timagenes had started a revolt against Roman rule while the Roman governor was away on campaign, and Zenobia's march on Egypt could have been explained as a campaign in the interests of Rome. It seems, however, that Timagenes may have been an instigator sent earlier by Zenobia to provide an excuse for the invasion. The Syrians were at first successful but then were driven out of Egypt by the returning Roman forces. Not content to simply drive the invaders from Egypt, the Romans pursued the Syrians past the borders and north toward Syria, where the Syrians then mounted a counter-attack and decimated the Roman army.

Once she had Egypt, she then entered into diplomatic negotiations with the regions of the Levant and Asia Minor and added them to her growing empire. With Rome in turmoil, the rising, wealthy Palmyrene Empire would have been an attractive choice for the provincial rulers in these regions, and Rome remained too occupied with internal strife to do anything about Zenobia's expanding empire. Although it is clear that she was creating her own empire in opposition to Rome, she still did nothing to warrant open conflict with the empire.

By this time Aurelian was emperor, and Zenobia had coins minted displaying an image of Vaballathus on one side and Aurelian on the other as joint rulers of Egypt. She had inscriptions to Aurelian's honor placed in Palmyra and included his name on official correspondence. At the same time, however, she adopted the imperial titles of Augustus for Vaballathus and Augusta for herself, titles which were the privilege of the royal family of Rome alone. She also conducted trade agreements, negotiated with the Sassanid Persians, and added territories to her empire without consulting Rome or even considering Rome's interests. By 271 CE she ruled over an empire which stretched from modern-day Iraq across through Turkey and down through Egypt.

Zenobia & Aurelian

While the other emperors had failed to notice what Zenobia was doing, or simply did not have the resources to do anything about it, Aurelian was a very different kind of ruler. He had risen in the ranks from infantryman to general and, now, to emperor, and he was a soldier first and politician second. When he assumed rule he had to contend with defeating the Vandals, Alemanni, and the Goths but, by 272 CE, he was ready to reclaim the eastern provinces from Zenobia. He did not send envoys with letters asking for an explanation nor did he wait for Zenobia to offer one on her own; he marched on the Palmyrene Empire with his entire army.

Entering Asia Minor, he destroyed every town and city loyal to Zenobia and fought off various robber attacks while on the march, until he reached Tyana, home of the famous philosopher Apollonius of Tyana whom Aurelian admired. In a dream, Apollonius came to Aurelian and counseled him to be merciful if he wished to obtain victory, and so Aurelian spared the city and marched on. Mercy proved to be very sound policy because the other cities recognized that they would do better to surrender to an emperor who was merciful than incur his wrath by resisting. After Tyana, none of the cities opposed him and sent word of their allegiance to Aurelian before he ever reached their gates and so, soon, he arrived in Syria.

Whether Zenobia had tried to make contact with Aurelian before this is not known. There are reports of letters between them once he reached Palmyra, but they are thought to be later inventions. His letter to her at the start of his campaign demanding her surrender and her arrogant response, given in the Historia Augusta, are also thought to be fabrications created to highlight Aurelian's merciful and reasonable approach to the conflict as contrasted with Zenobia's haughty response.

While Aurelian had been on the march, Zenobia had rallied her troops and the two armies met outside the city of Daphne at the Battle of Immae in 272 CE. Aurelian won the engagement by feigning retreat and then swinging about in a pincer formation once the Palmyrene forces were tired from pursuit. The Palymyrians were routed and then slaughtered. Zenobia herself, along with her general Zabdas, fled to the city of Emesa where she had more men and, also, stored her treasury.

Aurelian pursued her while she regrouped and reorganized her forces, and the armies met again in battle outside of Emesa where the Romans were again victorious using precisely the same tactic they had used at Immae. They pretended to retreat in the face of the Palmyrian cavalry, which pursued, and then turned and attacked them from an auspicious position. The Palmyrian forces were destroyed and Aurelian took the city and, it is assumed, plundered the treasury. Zenobia, however, had again escaped.

She went to Palmyra where she prepared the city for defense, and Aurelian followed close behind, besieging the city. The historian Edward Gibbon writes, "She retired within the walls of her capital, made every preparation for a vigorous resistance, and declared, with the intrepidity of a heroine, that the last moment of her reign and of her life should be the same" (131). Whether she declared anything like that is not known, but it seems clear that she was hoping for reinforcements and aid to come from the Persians and, when it failed to arrive, she fled Palmyra with her son on the back of a camel and tried to reach safety in Persia.

When Aurelian entered Palmyra and found her gone, he sent cavalry to apprehend her, and she was taken prisoner while trying to cross the Euphrates River. She was brought back to Aurelian in chains where she protested her innocence and blamed her actions on the bad advice given her by her advisors, chiefly Cassius Longinus, who was promptly executed. Zenobia was then brought back to Rome.

Zenobia's Final Days

What happened to her next varies with the account one reads. According to Zosimus, she and her son drowned in the Bosphorus while being transported back to Rome, but he also claims she arrived in Rome, without her son, was put on trial, and acquitted; after which she lived in a villa and eventually married a Roman.

The Historia Augusta relates the story of her being paraded through the streets of Rome in gold chains and heavily-laden with jewelry during Aurelian's triumph parade, after which she was released and given a palace near Rome where she "spent her last days in peace and luxury". Zonaras claims she was taken back to Rome, never was paraded through the streets in chains, and married a wealthy Roman husband, while Aurelian married one of her daughters.

Al-Tabari, like the other Arabian writers, does not mention Aurelian or Rome in his narrative at all. In Al-Tabari's account, Zenobia murdered a tribal chief named Jadhima on their wedding night, and his nephew sought revenge. The nephew pursues her to Palmyra where she escapes on a camel and flees to the Euphrates. She had earlier ordered a tunnel dug beneath the river in case her plans went wrong and she needed to escape, which, in the story, she is just entering when she is caught. She then either kills herself by drinking poison or, in another version of the story, is executed.

The end of Zenobia's life, then, depends upon which source one finds most credible. The Historia Augusta has long been recognized as an unreliable source that often manufactures dates, events, and even people in order to present a certain version of the reigns of the Roman emperors it deals with. Stoneman writes:

On several aspects of her interests and character we are given plentiful information by the Historia Augusta - though it must be remembered that little of the colorful detail that work offers us should be believed, since the author, like many ancient historians, wrote what he felt ought to have been true. (112)

The accounts of Zonaras, and Zosimus especially, are considered more reliable, and it seems likely that she would have been brought to Rome by Aurelian but may not have been made part of his triumph. Aurelian was very concerned over what the Romans would think of his conquest of a woman and also of the shame of Rome in allowing a woman to grow so powerful that she had held a third of the empire in her grasp.

It seems unlikely that he would have wanted to draw any more attention to Zenobia than was necessary, and the famous tale of her being paraded through Rome in golden chains, which has been represented in painting and sculpture since, is most likely fiction. The story of her trial, acquittal, and later life in Rome is, therefore, the most probable. There is no record regarding when or how she died, but no western sources indicate that she was executed, and it is thought that this version of her death was introduced to her legend through the Arabian versions of her story.

Zenobia became one of the most popular figures of the ancient world in the legends of the Middle Ages, and her legacy as a great warrior-queen and clever ruler, surrounded by the wisest men of her time, influenced painters, artists, writers, and even later monarchs such as Catherine the Great of Russia (r. 1729-1796 CE), who compared herself to Zenobia and her court to that of Palmyra. The story of her life was transmitted largely to these later generations through the Historia Augusta and Gibbon's work which presented the Queen of Palmyra as an honorable and worthy adversary of Rome and a great heroine of the ancient world, and this is how she is still remembered in the present day.