The mythology of ancient Persia originally developed in the region known as Greater Iran (the Caucasus, Central Asia, South Asia, and West Asia). The Persians were initially part of a migratory people who referred to themselves as Aryan, meaning “noble” or “free” and having nothing to do with race.

One branch of these Aryans settled in and around the region now known as Iran (originally known as Ariana – “the land of the Aryans”) prior to the 3rd millennium BCE and are referred to as Indo-Iranians; another branch settled in the Indus Valley and are known as Indo-Aryans.

Since both of these originated from roughly the same environment and culture, they shared a common religious belief system, which would develop in time as the Vedic lore and Hinduism of India and the Early Iranian Religion and Zoroastrianism of Persia, all of which share key concepts and types of supernatural beings. Belief in such beings and their stories – designated in the modern-day as 'mythology' – was simply their sincere religious system, as valid to them as any religion is to an adherent in the present. This so-called 'mythology', in fact, would go on to inform Zoroastrianism which, in turn, would influence the development of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Sources & Development

The ancient Persian religious tradition was passed down orally, and the only written texts relating to it come from after the prophet Zoroaster (c. 1500-1000 BCE) initiated the reforms which would become Zoroastrianism. The Avesta (Zoroastrian scriptures) is the primary source in the section known as the Yasht which deals with pre-Zoroastrian deities, spirits, and other entities. Other information on pre-Zoroastrian religion comes from later works known as the Bundahisn and the Denkard and, to a lesser extent, the Vendidad.

The Vendidad text provides insight on how one should practice Zoroastrianism and mentions various entities and rituals which predate the founding of the religion. The other major sources for Persian mythology are the Shahnameh (“The Book of Kings”) written by the Persian poet Abolqasem Ferdowsi (l. 940-1020 CE) drawing on the much earlier oral tradition, and the popular One Thousand Tales (better known as The Arabian Nights), written during the Sassanian Period (224-651 CE) and also based on oral tradition.

The early Iranian deities were almost completely reimagined by Zoroaster but many retained their original function to greater or lesser degrees. How these deities were venerated by the pre-Zoroastrian Persians is unclear but it is certain that rituals involved fire (considered a divine element and also a god), were conducted outdoors, and elevated the supreme principle of Goodness personified in the being of Ahura Mazda, king of the gods.

Creation & the Problem of Evil

The world, seen and unseen, was created by Ahura Mazda, the source of all good and all life. Ahura Mazda was uncreated and eternal and, by his goodness, made all that was known in seven steps:

- Sky

- Water

- Earth

- Plants (vegetation, crops)

- Animals

- Human Beings

- Fire

Sky was an orb suspended in the midst of nothingness and, within it, Ahura Mazda released waters and then separated the waters from each other by earth. The sky element rose high above the earth and passed beneath it. Upon the earth, Ahura Mazda spread all different kinds of vegetation and imbued it with its own life and then created Gavaevodta, the Primordial Bull (also given as “the uniquely created bull”, Primordial Bovine, and Primordial Ox) who would give life to all other animals which would feed on, and fertilize, the vegetation.

At this point, Ahura Mazda's supernatural enemy enters the narrative – Angra Mainyu (also known as Ahriman) – who embodies chaos, darkness, and evil. The Avesta gives no origin for this entity and seems to assume a prior knowledge among its audience of Angra Mainyu's existence and beginnings. The later sect of Zorvanism made Angra Mainyu the twin brother of Ahura Mazda, but this dualism was (and is) rejected by traditional Zoroastrians.

The 19th century CE German Orientalist Martin Haug (l. 1827-1876 CE) sought to resolve this problem of the origin of evil in a world created by an all-powerful and benevolent Ahura Mazda by claiming Angra Mainyu did not actually exist as a deity but was rather the destructive/negative energy-discharge of the creative act of the god. In this view, Angra Mainyu takes on sentience and power from the act of creation but is himself a created being and, ultimately, will fail against the greater power of the creator. Haug's answer seems to fit with Zoroaster's original vision but whether it would apply to pre-Zoroastrian understanding is unknown.

After Ahura Mazda created the world and Gavaevodta and set all in motion, the Primordial Bull was killed by Angra Mainyu for no reason other than that he could. Gavaevodta's corpse is taken to the moon and purified, and from the bull's purified seed, all animals come into being. Ahura Mazda thereby sets the paradigm, repeated in many other instances, of turning Angra Mainyu's efforts at destruction to positive ends.

Once animals and plant life were in place, Ahura Mazda created the first man, Gayomartan (also given as Gayomard, Kiyumars) who is beautiful and “bright as the sun” and so attracts the attention of Angra Mainyu who kills him. The sun purifies Gayomartan's seed in the ground, and 40 years later, a rhubarb plant comes from it and grows into the first mortal couple – Mashya and Mashyanag – into whom Ahura Mazda breathes the spirit of life which becomes their souls. Mashya and Mashyanag live in complete harmony with the animals of the world, each other, and Ahura Mazda until Angra Mainyu comes into their paradise and seduces them by claiming that he is their creator and master of the world and that Ahura Mazda has been deceiving them.

Confused, the couple doubt their true creator's word and accept the lie of Angra Mainyu and so sin enters the world and harmony is lost. The couple cannot conceive for 50 years after their fall and, when Mashyanag finally does give birth, she and Mashya eat the children because they have lost any sense of balance and reason. Many years after this, another set of twins is born who will become the progenitors of humanity. Owing to the first couple's acceptance of the lie, however, paradise has been lost and humans will now live in strife with the natural world and each other.

Humans were granted the gift of free will by Ahura Mazda, which is how they were able to choose to believe Angra Mainyu's lies over their creator's truth, and so the meaning of human existence comes down to the exercise of that free will in choosing good over evil, Ahura Mazda over Angra Mainyu. However one chose would then dictate the quality of one's life and, naturally, one's afterlife.

Life & Afterlife

If one chose to follow Ahura Mazda, one would live a good and productive life in harmony with others and one's environment; if one chose Angra Mainyu, one lived in opposition to the truth and became a source of confusion and strife. When a person died, their soul hovered around the corpse for three days while the gods tallied up their spiritual credits and debits in life. The soul was then called to cross a dark river to the land of the dead during which good souls were separated from bad ones (a process known as the Crossing of the Separator). Afterwards, justified souls went on to paradise where they were reunited with those who had gone before; evil souls were dropped into a dark hell of torment.

Gods & Spirits

The supernatural entities who decided one's fate, and also kept the universe functioning, came into being through the emanations of Ahura Mazda. Among the best known are:

- Mithra – god of the rising sun, covenants, and contracts

- Hvar Ksata – god of the full sun

- Ardvi Sura Anahita – goddess of fertility, health, water, wisdom, and sometimes war

- Rashnu – an angel; the righteous judge of the dead

- Verethragna – the warrior god who fights against evil

- Vayu – god of the wind who chases away evil spirits

- Tiri and Tishtrya – gods of agriculture and rainfall

- Atar – god of the divine element of fire; personification of fire

- Haoma – god of the harvest, health, strength, vitality; personification of the plant of the same name whose juices brought enlightenment

There were a number of other entities in addition to these, among the most important being the angel Suroosh – guide of the dead – and Daena – the Holy Maiden – both of whom met the soul at the crossing to the afterlife. This world, and the next, was thought to be inhabited by invisible spirits who, just like humans, were engaged in the cosmic struggle between good and evil. The ahuras were good spirits and the daivas were evil; both influenced human life and thought.

Central to one's spiritual journey was how well a person treated animals, especially dogs. Dogs in ancient Persia were accorded an especially high status and, in later Zoroastrian belief, guarded the Chinvat Bridge (which would replace the image of the dark river in the Crossing of the Separator) spanning the abyss between life and death. Dogs would welcome a justified soul and reject those who had been condemned.

Supernatural Creatures

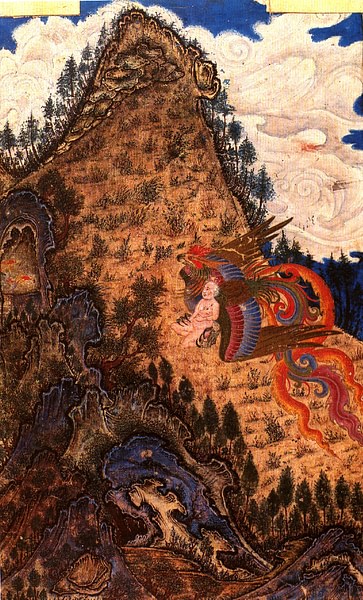

The dog features prominently in one of the most popular and enduring figures from Persian mythology, Simurgh, the so-called dog-bird. Simurgh was an enormous bird with the head of a dog, body of a peacock, and claws of a lion, large enough to lift an elephant with ease, who lived in cycles of 1,700 years before plunging into a fire of its own making to die and be reborn (precursor to the later myth of the Phoenix). Simurgh originally appears as the Great Falcon known as Saena who sits high in the branches of the Tree of All Seeds at the center of the world and, by flapping her wings, sends seeds scattering through the air which find their place in the earth through wind and rain.

Birds feature prominently in Persian mythology on either side of the struggle between good and evil. The great bird Chamrosh (with a dog's body and eagle's head and wings) assists in distributing seeds from the Great Tree and also protects Persians against threats by non-Persians while, on the opposing side, is the enormous bird Kamak who seeks to thwart whatever good Chamrosh intends. The Huma bird, similar to Simurgh in many respects, conferred kingship and held all the wisdom of the ages while the giant bird of prey known as the Roc (or Rukh) dispensed justice upon those who thought they could escape it.

One of the most feared supernatural entities was the Al (also known as the Hal and Umm Naush), a nocturnal demon who fed on the life-force of newborns. The Al were part of a larger body of evil and dangerous spirits known as khrafstra who troubled, disrupted and, at times, ended human lives. The khrafstra were invisible but manifested their intentions through observable nature in stinging ants, wasps, crop-destroying beetles, spiders, frogs, rodents, serpents, and beasts of prey. The dog was considered the best protection against these spirits as well as their physical manifestations.

One of the most potent invisible spirits was the Jinn (also known as Djinn and best known as Genies) who, unlike any other entity, were collectively neutral in the war between good and evil. Some Jinn were malevolent and some benign but, overall, they seem to react to circumstances and individual prompts. A Jinn might grant one wishes but could twist and betray the outcome in doing so or, conversely, could simply be helpful outright. Jinn were thought to especially favor lonely places such as desert plains and oases so amulets were carried by merchants and travelers for protection from their influences.

Similar to the Jinn were the Peri (fairies) who could be mischievous or helpful. Peris are tiny, beautiful, winged creatures – usually female – who can deliver important messages from the gods or, just as easily, steal and hide some important object or misdirect a person. They were allegedly imprisoned in their fairy-form until they had atoned for a past sin but were neither human souls nor immortal entities. If their purpose was atonement, they seem to have been collectively bad at their jobs since tales concerning them show them causing trouble as often as resolving it.

Another great threat to order and human happiness was the dragon (known as azhi) and the most fearsome of these was Azhi Dahaka who is described as “three-mouthed, the three-headed, the six-eyed, who has a thousand senses…most powerful, to destroy the world of the good principle” (Yasht 9.14; Curtis, 23). The dragon Azhi Sruvara preyed on humans and horses while another, Gandareva, stirred up the seas and sank ships.

Famous Myths

The stories of these creatures, gods, and spirits – as well as the heroes who contended with them – were passed down in a long oral tradition until they were included in parts of the Avesta and, more fully, in the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi written between 977-1010 CE. The Shahnameh is an enormous epic spanning generations but, roughly speaking, tells the story of the forces of good, symbolized by the kingdom of Iran, battling those of chaos and evil personified by the kingdom of Turan.

Long before their conflict begins, the first great hero is King Yima (also given as Yama), who rules over the known world with justice and devotion, banishing death and disease and elevating the lives of the people throughout his realm. He is given power by the gods as a reward for his selfless devotion and uses it wisely: when the world becomes overpopulated, he simply enlarges it, providing more space and resources for humans, animals, and vegetation to live together peacefully.

In a story which some scholars cite as a direct influence on the later biblical Noah's Ark tale, Yima also saves the world from destruction. The gods tell Yima that a hard winter is coming and he should gather a man, woman, the seeds of all kinds of vegetation, and two of each kind of animal in a large three-tiered barn. Yima does so, and the world is saved. After a reign of over 300 years, however, he begins to listen to the lies of Angra Mainyu and so he sins and the divine grace leaves him. Afterwards, his successors must struggle to maintain just rule since deception and trickery will now regularly play a part in politics.

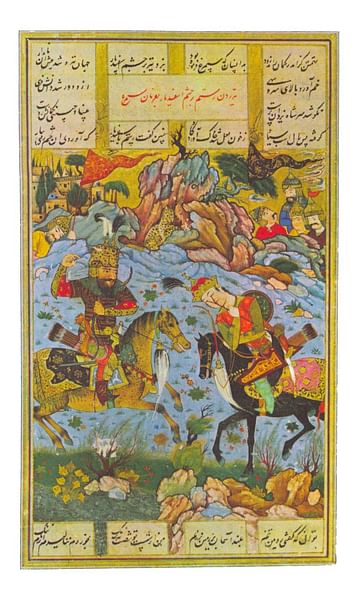

The greatest Persian hero is Rustum (also given as Rostom and Rustam) who is the grandson of the hero Sam and son of the equally heroic Zal. Sam longed for a son and was overjoyed when Zal was born but that moment vanished quickly when he looked at the boy and saw he had bright white hair. Interpreting this as an evil omen, Sam abandons the newborn in the Alburz Mountains and leaves him to die. The boy is taken by Simurgh, however, who raises him as her own son, and he develops amazing strength and superhuman powers.

After some time, news comes to Sam's court of a great hero living in the mountains and, at the same time, Sam dreams of his son alive again and is encouraged to go find him. Simurgh tells Zal to return to his father and the world of humans but gives him a feather (in some versions, three feathers) which he should use to summon her if he needs help. Zal becomes a great prince and marries the princess Rudabeh who has a difficult time giving birth to their son.

Zal summons Simurgh who teaches him how to deliver the child through Caesarian section and also instructs him in the medicinal use of plants. Rustum is born and, after one day, is the size and strength of a one-year-old and continues growing quickly to “the height of a cypress tree and with the strength of an elephant” (Curtis, 39). He becomes the great hero of the Iranian forces against those of Turan and, though eventually killed through deceit and trickery, he prevails and order is restored.

Conclusion

There are, of course, many other famous stories from Persian mythology – the Rustum tales alone are epic, and the Shahnameh weaves these with others in 50,000 rhymed couplets, making it longer and more thematically complex than other famous works like The Epic of Gilgamesh or Homer's Iliad – which explore and expand upon the theme of good vs. evil and order triumphing over chaos. The long tradition of telling these tales attests to the popularity of their rich imagery and dramatic tension as they were repeated orally for centuries before they found written form.

The Avesta was only finally written down during the reign of Shapur II (309-379 CE) and codified/revised under Kosrau I (r. 531-579 CE) of the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE), while the Shannameh was only completed at the beginning of the 11th century CE. Even so, the oral tradition of the Persians is thought to have influenced the religious systems of other cultures many centuries earlier. Persian mythological motifs are evident in aspects of Vedic, Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Greek religious systems and, through later development by Zoroastrian thinkers, would come to influence significant aspects of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, among others; suggesting Persian mythological thought as foundational to religious belief worldwide in the modern era.