Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) was an Austrian composer, most famous for his nine grand symphonies and his church music. Never quite gaining full recognition for his work until he was in his sixties, Bruckner's music, with its strong spiritual emphasis, continues to divide the music community, creating admirers and detractors in equal measure.

Early Life

Anton Bruckner was born in Ansfelden, Upper Austria, on 4 September 1824. His father was a schoolmaster, devout Catholic, and the village organist. Anton had five younger siblings, and he learnt music from his father at an early age. Aged 13 and following his father's death, Anton joined the choir at the nearby Abbey Church of the monastery of Saint Florian, run by Augustinian monks. He followed in his father's steps when he gained employment as a village schoolmaster in 1840. Over the next five years, he moved around various towns and villages, always teaching. Anton again repeated his father's career steps when he, too, became an organist, this time at the Saint Florian Abbey. He had returned to Ansfelden in 1845 where he continued to work as a teacher, but once he gained a formal teaching qualification, he was able to gain a better salary and a position at St. Florian's. His organ skills soon shone through in church services. Anton was keen to compose, and early works include the Missa solemnis in B flat, but he was ambitious for more than local fame.

In 1855, Bruckner moved to Linz, where, from the next year, he worked as the first organist in the great cathedral, a position that included free accommodation. Bruckner held the organist position for 12 years, and the instrument would influence his composing style. Eager to improve his composing skills, he followed a correspondence course supplied by the Vienna Conservatory, which focussed on harmony and counterpoint. This was an unconventional route for someone who became a master of his art, certainly, it was a time-consuming one. Bruckner graduated in 1861 with great honours, one teacher ruefully remarked, "If I knew one tenth of what he knows, I'd be happy" (Sadie, 274). Bruckner was not quite finished with his studies, though. The 37-year-old next learnt more about orchestration and symphonic form under Simon Sechter (1788-1867), a respected teacher at the Vienna Conservatory. Bruckner travelled to Vienna once a week to have his lesson. Another teacher was Otto Kitzler, conductor at the Linz Theatre.

Bruckner was influenced by the work of Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) and Johannes Brahms (1833-1897). Even more influential than these composers was the work of Richard Wagner (1813-1883), in particular his epic opera Tannhäusser, which Bruckner first heard in 1863, and then, personally invited to attend by the composer, Wagner's Tristan in Munich in 1864. Turning 40, Bruckner was finally inspired to make his mark in the wider world of classical music. He composed three masses, including Mass in D minor (completed in 1864), before turning to what would be his preferred format, the symphony.

Character

Bruckner is described by the music historian H. C. Schonberg as:

…a simple man, incredibly rustic and naïve. He had a shaven head and a country dialect; he wore homespun and ill-fitting clothes…A child of nature, he was not well read, was completely unsophisticated, would blurt out the first thing that came into his mind.

(504)

Bruckner's lack of sophistication (or was it his humour?) is evidenced in one episode involving the great conductor Hans Richter (1843-1916). Richter conducted one of the composer's symphonies, and at the end of the performance, as Bruckner went to shake the conductor's hand, he also gave him a coin saying "Take this and drink a mug of beer to my health" (Schonberg, 504). Richter had the coin put on the end of his watch chain.

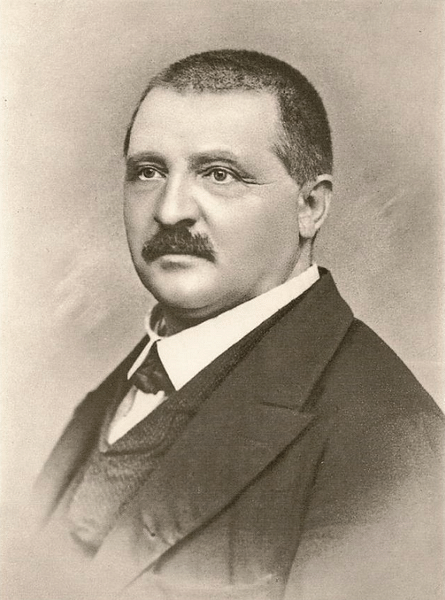

Bruckner was "diffident by nature and fatally lacking in self-esteem" (Wade-Matthews, 407). He made several marriage proposals in his lifetime, but none of the startled teenagers ever accepted such advances from a man they hardly knew. He remained a bachelor all his life. This is perhaps just as well since the historian M. Steen notes that "Bruckner was an impossible person who suffered nervous breakdowns and extraordinary obsessions" (573). These obsessions, besides marriage proposals, included music examinations (he took nine in all), multiple daily prayers, and counting things. He counted everything he ever came across, "whether windows, weathercocks, church crosses, dots, buttons or ornamental figures" (ibid). One thing Bruckner must surely have counted with mounting trepidation was his growing number of symphonies. In classical music, there is what some have called the 'curse of the ninth', the belief that no composer can write a tenth symphony, since by the ninth they have so perfected their art that they have reached too close to God, or Infinity if one prefers. The 'curse' may be nonsense, but it is a curious coincidence that several composers did not get past number nine, notably Beethoven, Franz Schubert (1797-1828), and Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904). As we shall see, Bruckner would join the "nine only" club, as would his contemporary and admirer Gustav Mahler (1860-1911).

The Symphonies

Bruckner's reputation as one of the great composers largely rests on his nine large-scale symphonies. Starting on his first in 1865, Bruckner worked on symphonies for the next 30 years. By then the symphony format was well-established as an orchestral work of four movements, although Bruckner's were longer than most.

The composer was not satisfied with his first stab at the symphonic form, and so this work is known as Symphony 0. Bruckner pressed on regardless. Symphony No. 1 was completed in 1866, Symphony No. 2 in 1872, and Symphony No. 3 in 1877. All three hardly set the music world alight. As the musicologist Denis Arnold notes, the first three symphonies were "considered eccentric and not successful in performance (Bruckner's own conducting being responsible in the case of the Third)" (277). There were a few admirers. Wagner particularly liked the opening movement of the Third Symphony.

Bruckner was struggling to earn a living at this point, and only his private teaching kept him from ruin. He persevered with the symphonic format. Symphony No. 4 is (somewhat misleadingly) subtitled 'The Romantic' and was completed in 1881. It premiered that year with a performance conducted by Hans Richter. Symphony No. 5 was not performed until 1894. It is described by R. Osborne in the following terms: "The Fifth does, indeed, resemble a huge cathedral, with everything gathering to the end of the massive Finale, itself an epic structure involving flashbacks to earlier movements and a huge fugal development." Like other works, Bruckner includes in the scherzo references to traditional Upper Austrian dance rhythms. Symphony No. 6 was not performed in full in Bruckner's lifetime, but it impressed Mahler enough to conduct it personally in 1899.

Symphony No. 7 was completed in 1883 and premiered in Leipzig on 30 December 1884; it was the greatest triumph of Bruckner's career so far. Osborne describes it as: "perhaps Bruckner's most perfectly wrought work, his richest and most luminous utterance." Symphony No. 8 was completed in 1890 and was also a success when first performed, again with Richter as the conductor. Osborne remarks that it is "undoubtedly Bruckner's most powerful and all-encompassing symphonic work, one of the supreme achievements of post-Renaissance European art". Bruckner's final symphony, No. 9, was left incomplete when he died. The missing last movement, which Bruckner wrote some sketches for, has been 'completed' by several later composers, but the symphony is usually performed with only its first three movements.

Bruckner's symphonies, like those of Mahler, "brought the Romantic symphonic tradition to its zenith," but, unlike Mahler's work, "Bruckner's symphonies express triumphant faith, their almost cathedral-like proportions infused with exciting orchestral power and poetry" (Sadie, 274). Bruckner is not everyone's cup of tea. The slow, stately openings of his symphonies mean that they seem to take an age to really get going for some, while others admire what could be described as "unhurried serenity" (Schonberg, 507). There is, for some, too much music in them and too much repetitiveness, which has led several critics to state that Bruckner simply wrote nine versions of the same symphony, an exaggeration perhaps, as critics are wont to make.

Often misrepresented as a composer of music in the shadow of Wagner, Arnold describes important differences:

Certainly, his music shows some Wagnerian harmonic and melodic traits, but there are fundamental differences between the two composers: Bruckner was little interested in drama, working instead in long phrases and extended groups of themes; these are not so much 'developed' as juxtaposed (and are often separated by characteristically long pauses). And although Bruckner used 'Wagner tubas', his orchestration is less subtle than Wagner's, and often resembles the block effects of organ registration.

(278)

The Classical Music Encyclopedia agrees with this assessment:

Stylistic hallmarks include vast block-like structures within which strident fanfares or soaring melodies build to huge climaxes, dramatic pauses, brass chorales and rich chromatic harmony.

(275)

Despite his preoccupation with symphonies, Bruckner continued throughout his career to compose music for religious purposes, notably his Mass in E minor, composed in 1866, the Mass in F minor, completed in 1868, Te Deum, composed in 1884, and the Psalm 150 of 1892. He also revised his earlier Mass in D minor in 1876 and again in 1881.

Life in Vienna

In 1867, Bruckner suffered a breakdown, probably from the effects of persistently overworking himself. The composer moved to Vienna in 1868 and lived the rest of his life in the Austrian capital. He took up a position as a professor of music at the Vienna Conservatory, actually the post his former teacher Sechter had held. His lectures on counterpoint and organ were well-received, despite the fact he often interrupted them with prayers when the appropriate bells rang from a nearby church. Bruckner's reputation was now high enough to earn a government grant, which allowed him more time to compose, although he also took on the role of organist at Vienna's Imperial Chapel and taught private pupils.

Bruckner's reputation spread abroad, and he performed organ recitals in both Paris and London, which met with great success. The respective venues were Notre Dame Cathedral and the Royal Albert Hall. Back in Vienna, he became a lecturer in harmony and counterpoint at the city's prestigious university in 1876. He was not appreciated by everyone in Vienna. Bruckner's grand symphonies were disliked by a group of critics already united in their hatred of Wagner. Wagner's influence on Bruckner was clear (although as noted above, the two composers produced music with distinct differences), but the Austrian composer made the Wagnerian link even more obvious with little touches like calling his third symphony the "Wagner Symphony". Wagner was equally taken, once declaring, "Bruckner! He is my man!" (Wade-Matthews, 406), and, on another occasion, stating Bruckner was the "only symphonist to approach Beethoven" (Sadie, 275). Bruckner's Mass in F minor, first performed in 1872, was praised by Franz Liszt (1811-1886). Brahms, on the other hand, described Bruckner's works as "symphonic boa-constrictors" (Arnold, 278) and the composer himself as "a poor deranged man" (Steen, 573). Brahms could not, it seems, forgive Bruckner for being a fan of Wagner.

The highly conservative Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra was a nest of this anti-Wagner-Brucknerism and rejected several of his symphonies. Even those they did put on were not usually performed how the composer would have wished them to be heard. Bruckner was always something of a tinkerer, never being quite satisfied that a piece was absolutely finished. This, and his lack of self-confidence, led him, perhaps unwisely, to try to make his work more appealing to his critics by shortening some of the symphonies and altering the scores here and there. Several editors have attempted to return Bruckner's symphonies to their original form, but there is disagreement as to whether this has been achieved according to Bruckner's original intentions or not (especially regarding Symphonies 2, 3, and 8).

Death & Legacy

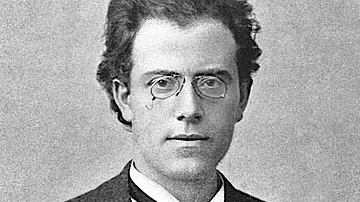

In his final decade, Bruckner began to receive official recognition for his contribution to music. In 1886, he was awarded the prestigious Order of Franz Josef, which he can be seen wearing in several portraits. In 1891, Bruckner received an honorary doctorate from the Vienna Conservatory.

Anton Bruckner died in Vienna on 11 October 1896. According to his instructions, his body was embalmed before being buried beneath the organ he had played so often as a young man in the Abbey Church of Saint Florian.

Bruckner's musical legacy is ambiguous. Known and much-liked by many classical enthusiasts, his name is rarely mentioned outside the field. As Arnold notes, Bruckner's "music tends to be liked very strongly (as in Austria) or dismissed as lacking proportion between length and effect" (278). The International Bruckner Society was created in 1929 to try and sort out definitive editions of his works. Bruckner was much admired by fellow Austrian Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), but despite the association with Nazi Germany, his symphonies grew much more popular in the second half of the 20th century thanks to celebrated conductors like Herbert von Karajan (1908-89) recording all nine of them. Bruckner's symphonies have since grown to become established features of the modern repertory.