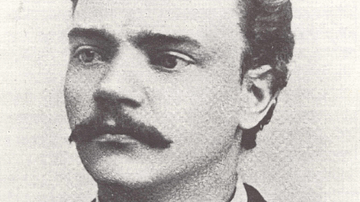

Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) was a Czech composer best known for his symphonies, symphonic poems, operas, and chamber music. Dvořák's best-loved works include his 9th Symphony (From The New World), the American quartet, and his Slavonic Dances, which take inspiration from Czech folk melodies and dance rhythms.

Early Life

Antonín Leopold Dvořák was born in the village of Nelahozeves near Prague on 8 September 1841. Bohemia was then part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Antonín's father was an innkeeper, but Antonín was determined to take an entirely different career path despite his father's wishes he either become a butcher like his uncle or continue the family business. He learnt to play the violin, studied for a time in Česká Kamenice, and, in 1857, enrolled at the Prague Organ School. He graduated in 1859. Dvořák's first paid work as a musician was as a member of the Provisional Theatre's orchestra where he played viola. He worked in the orchestra, which was then conducted by Bedrich Smetana (1824-1884), until 1871 and supplemented his income by teaching, becoming extremely popular with his students.

Dvořák found sufficient time to begin composing. Still only in his early thirties, he had already built up a catalogue of compositions by the mid-1860s, which included two operas, four symphonies, a Cello Concerto, the Cypresses song-cycle, and several pieces of chamber music. In 1870, he composed his first opera: Alfred, and the next year a comedy Král a whlíf (King and Charcoal Burner), which had to be significantly revised before its premiere in 1874. On 9 March 1873, Dvořák came to the attention of Czech nationalists with his Dédicové bile hory (The Heirs of the White Mountains), a cantata. In 1874, the composer was appointed the organist at St. Adalbert's Church in Prague, a position he held for three years.

The composer's other great interest besides music, rearing pigeons, gardening, and walking in the Bohemian forest, was trains, likely set off by the opening of the Prague-Dresden line, which went through Nelahozeves, when Dvořák was nine years old:

He used to pay daily visits to the Franz-Josef Station in Prague, had all the timetables memorized, and was never so happy as when he could make friends with a locomotive engineer. He would send his pupils to the station to find out what engine was going on what train, or, when a pupil returned from a trip, would want to know what kind of train he had traveled on, and the name and model number of the locomotive. (Schonberg, 434)

The Slavonic Dances

Dvořák's big breakthrough came in 1875 when he entered his 3rd and 4th Symphonies and won a prestigious music prize awarded by a jury which included the noted music critic Eduard Hanslick (1825-1904) and Johannes Brahms (1833-1897). The German composer became a strong supporter of the younger Czech composer, lamenting once, "I should be glad if something occurred to me as a main idea that occurs to Dvořák only by the way" (Wade-Matthews, 386). The prize included an annual income from the Austrian state and instantly relieved the composer of his financial difficulties, which most of the time had been intense. Brahms recommended Dvořák to his publisher Simrock, who took heed and commissioned the Slavonic Dances, a set of eight orchestral works in the style of folk music but with original melodies. These were first performed in 1878 and were extremely popular, the composer became famous across Europe. Other commissions quickly followed, including the Moravian Duets, the three Slavonic Rhapsodies, and various works for strings, wind instruments, and piano. In 1882, his tragic opera Dimitrij was successfully premiered.

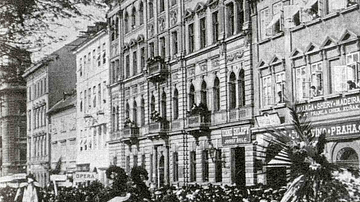

Now even places like New York were staging concerts of Dvořák's works. London was a happy hunting ground, and Dvořák toured there conducting his work in 1884, including Stabat Mater. The next year, the Royal Philharmonic Society commissioned what was his 7th Symphony, and two choral works were staged at music festivals in Birmingham (Svatehní – The Spectre's Bride cantata) and Leeds (St. Ludmila oratorio). In 1887, he completed his Piano Quintet, and in 1889, his 8th Symphony. In November 1889, Dvořák's opera The Jacobin was premiered in The National Theatre in Prague.

Musical Style & Nationalism

Dvořák is regarded as a nationalist composer since, like Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893), Edvard Grieg (1843-1907), and Jean Sibelius (1865-1957), amongst others, he blended the folk melodies and rhythms of his country with the symphonic techniques of Classical music. These Bohemian inspirations included the lively polka and the even livelier furiant dances, and the melancholic dumka folk song.

Dvořák was a pupil of and then good friends with fellow-Czech composer Bedrich Smetana. Smetana was also a key figure in the use of national motifs in his work. As the music historian C. Schonberg puts it, "Smetana was the one who founded Czech music, but Antonín Dvořák…was the one who popularized it" (431). Dvořák "remained throughout his entire creative span the happiest and least neurotic of the late Romantics. 'God, love, motherland' was his motto" (Schonberg, 432).

As The New Oxford Handbook to Music summarises:

Dvořák preserved a strongly individual style of melody and development...the strength of his style was due in part to the national elements in his music which so delighted contemporary audiences. Although he rarely quoted folksongs, his melody and rhythm were profoundly influenced by the music of his country.

(593)

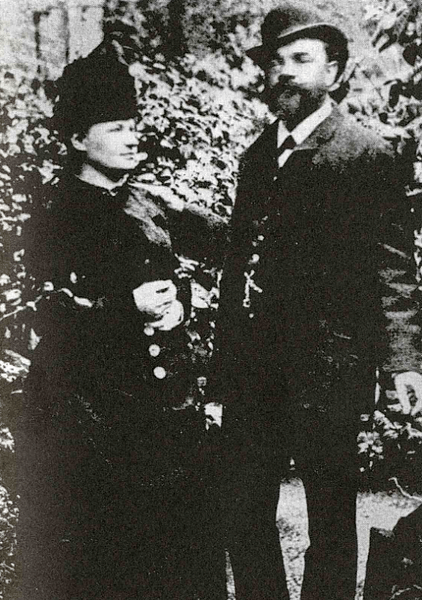

Family

Dvořák became infatuated with one of his music pupils, Josefina Čermáková, who was the daughter of a Prague goldsmith, but his feelings were not reciprocated. The composer then turned to Josefina's younger sister, Anna. The couple married in 1873, Anna being already three months pregnant – Dvořák was a staunch Roman Catholic. The couple had three children who all died between 1875 and 1877. A fourth child was born in 1878, Otilie, and she survived infancy. Otilie married the composer Josef Suk (1874-1935), but she died in her twenties. More children followed through the 1880s.

Dvořák and Anna lived in a country house near Przibram on the estate of his brother-in-law. The house was called Villa Rusalka, named after the water nymph of Bohemian legend. Here Dvořák kept his pigeons and doves and cultivated an English garden, resisting persuasive and persistent encouragement from Brahms and others to relocate to Vienna.

International Acclaim

Into the 1890s, Dvořák continued to win international acclaim for his work. In 1891, the composer was honoured with a doctorate from the University of Cambridge. In 1892, the composer visited the United States, taking up his new position as director of the National Conservatory of Music in New York, a post he held for three years and which involved him expanding the Conservatory's intake of black students. The salary in New York was stupendous: equal to 30,000 gulden when back in Prague he had commanded a mere 1,200 gulden per annum. The position also included four months holiday a year, so he had plenty of time to continue his own composing. Dvořák had well and truly hit the big time in the United States. In 1893, Dvořák was invited to conduct at the Chicago World Fair. The composer opted to showcase his 8th Symphony (completed in 1890) and three of his Slavonic Dances.

From The New World

Undoubtedly, Dvořák's best-known symphony is his ninth, titled From The New World. It was completed in 1893. Appropriately enough, given its title, the work was composed while Dvořák was in his apartment in New York and in Spillville, Iowa, where he spent several summers with the large Czech community there. The work was in part inspired by (though never directly quotes) African-American spiritual and Native American music, as are several of his other pieces composed in this period. From The New World premiered at Carnegie Hall, New York, on 16 December 1893. The 9th Symphony continues to be a very popular piece: "The warm, mellow theme creates a sense of well-being in the listener that has ensured its continuing success" (Sadie, 279).

Dvorák's Famous Works

The most famous works by the composer Antonín Dvořák include:

Nine symphonies

Serenade for Strings (1875)

Stabat Mater (1877)

Moravian Duets (1878)

Slavonic Rhapsodies orchestral works (1878)

Slavonic Dances orchestral works (two sets: 1878 & 1886)

Symphonic Variations (1887)

Piano Quintet (1889)

Jakobín - The Jacobin opera (1889)

Requiem (1891)

Dumky Piano Trio (1891)

American Quartet (1893)

G-flat Humoresque piano work (1894)

Cello Concerto in B minor (1895)

Čert a Káča - Kate and the Devil opera (1899)

Rusalka opera (1900)

Death

In April 1895, Dvořák returned to Bohemia to take a teaching position at the Conservatory in Prague (he was awarded an honorary directorship in 1901). Still busy composing in his final decade, works of this period include several symphonic poems inspired by Czech folk tales from Erben's Kytice: Vodnik (The Water Goblin), Zlaty Polednice (The Noonday Witch), and Holoubek (The Wild Dove). There were two operas inspired by Czech fairy-tales/legends: Čert a Káča (The Devil and Kate), a comedy composed in 1899, and Rusalka, composed in 1900. The latter is described by the Classical Music Encyclopedia as "ravishingly lyrical and finely characterized" (278). The opera, widely regarded as Dvořák's finest, is similar to the "Little Mermaid" fairy-tale by Hans Christian Andersen (1805-1875) but reset in the Bohemian forest. The aria Song to the Moon has attracted many sopranos to record it ever since, notably Joan Hammond (1912-1996). Both Čert a Káča and Rusalka were very well-received at their premieres, but his next and final stage work, the opera Armida failed to ignite the public's imagination.

Antonín Dvořák died in Prague of a stroke on 1 May 1904. He was given a lavish state funeral befitting his status as a national hero. Dvořák, as a composer of international renown and teacher at the Prague Conservatory, hugely influenced the next generation of Czech composers. In particular, the Czech nationalist baton was passed on to Dvořák's star pupil, Josef Suk.

![Antonin Dvorak - Symphony No.9 in E minor - Herbert von Karajan, Berlin Philharmonic, 1966 [BD1080p]](/uploads/kraked/6/6-2971_ci_preview.jpg?v=1687180407-1744756458)