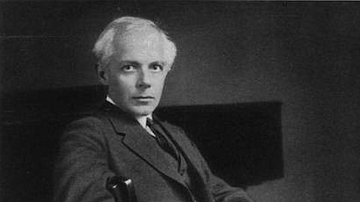

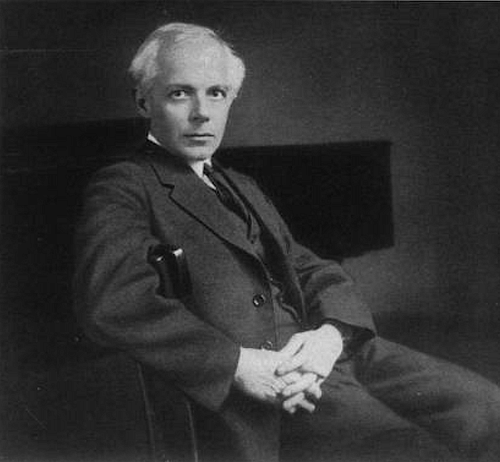

Béla Bartók (1881-1945) was an innovative Hungarian pianist and composer most famous for his classical works for piano and orchestra, string quartets, and songs, many of which present traditional Hungarian and other European folk themes. Bartók, a prodigious scholar and collector of folk songs, is widely considered one of the greatest musicians Hungary has ever produced.

Early Life

Béla Bartók was born on 25 March 1881 in Nagyszentmiklós (now called Sânnicolau Mare), then located in the Hungarian part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (but today located in Romania). Béla's father was a teacher in the local agricultural college, and his mother was a piano teacher. Béla's father died when he was seven years old, and so mother and son moved to Pressburg (called Pozsony by the Hungarians), today's Bratislava in the Slovak Republic. Béla's mother taught him to play the piano from the age of five. He showed a rare talent and was already performing in public by the age of eleven; he had started composing his own pieces even earlier, at the age of nine.

Béla turned down a free scholarship to study at the music academy in Vienna and instead decided to attend the Royal Hungarian Academy of Music in Budapest from 1898. Bartók graduated in 1903. First earning a living as a concert pianist, from 1907, Bartók worked as a piano professor at the Academy. Although the post gave Bartók some financial stability, it was not quite what he had hoped for; he remarked that he was, in truth, "a reluctant teacher and would have preferred a research post" (Steen, 722). Bartók continued to compose, with early influences coming from the works of Franz Liszt (1811-1886), Johannes Brahms (1833-1897), Richard Strauss (1864-1949) – particularly his symphonic poem Also sprach Zarathustra –, and Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971).

Bartók's character and drive is here summarised by the music historian H. C. Schonberg:

Bartók was a tiny, frail man with explosive psychic force, prepared to go his own uncompromising way even if his music was never played. A stubborn integrity and an all-encompassing humanism animated the man, and he would not swerve from his ideal of truth.

(656)

Folk Music

Bartók took a particular interest in Hungarian folk music (which was quite distinct from the Romani music that had interested composers like Brahms and Liszt). He published his first song collection in 1906. Bartók's position at the Academy gave him more time to devote to research, and so he investigated folk music from other regions, notably from Romania, Slovakia, and Transylvania. Bartók amassed a considerable collection of folk songs, both in print and by recording them on wax cylinders directly from local singers so that they could be played later on a phonograph and suitably catalogued. This collecting endeavour, which also involved writing scholarly articles on the findings and publishing collections for the public, was something he pursued with fellow Hungarian composer Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967). Bartók also composed more song anthologies of his own, the singer to be accompanied by piano.

Hungarian folk idioms can be heard in Bartók's collection of short piano pieces, The Ten Easy Pieces (1908); the 14 Bagatelles (1908) for piano; and the piano work Allegro barbaro (1911). They are also particualrly evident in the composer's last two string quartets. Bartók's promotion of Hungarian traditions was also seen in other ways such as his composition Dance Suite (Táncszvit) to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the union of Buda and Pest (1873). Bartók later arranged this work for piano.

Bartók also composed new arrangements for traditional folk songs like For Children, completed in 1909, which was a collection of 85 simple-to-play pieces for the piano. The Classical Music Encylopedia explains how Bartók worked with traditional themes:

For some of the melodies he collected he composed settings, which keep the tunes themselves intact providing them with often adventurous harmonizations. But Bartók aimed at more than mere quotation, seeking rather to absorb the complex modal structure of peasant melodies, which he saw as a means of freedom "from the tyrannical rule of the major and minor keys".

(387)

Stage Works

In 1911, the composer tried his hand at opera, producing the one-act A kékszakállú herceg vára (Duke Bluebeard's Castle) based on the French folktale of the bearded man who murders a series of wives but softened by the librettist Béla Balázs into a tale of despair and loneliness. The plot is summarised as follows by The New Oxford Companion to Music:

Bluebeard (bass)…takes Judith (soprano), his newest bride, home to his gloomy castle. She makes him unlock his secret doors one by one, and when she has penetrated his innermost secret she takes her place, another failure, among the other wives behind the last door, leaving Bluebeard in his loneliness.

(584)

The opera was entered into a competition but was rejected by the jury. Bartók had to wait until 1918 before the opera was finally put on the stage (in Budapest in May) since it was only then that the composer's reputation had been established through the success of his one-act ballet, A fából faragott királyfi (The Wooden Prince), staged in Budapest in 1917. Bartók was inspired to write another ballet in 1919, A csodálatos mandarin (The Miraculous Mandarin). However, he again had to wait many years to see his work performed to the public, this time the premiere came in Cologne in 1926. The Miraculous Mandarin caused controversy because of its risqué themes, particularly the scene where the title character is tempted by a prostitute to enter a robber's lair where he is stabbed and hanged but then insists on making love to the woman before he finally dies. The controversy over the ballet meant that it was not performed in Hungary until 1946. As with The Wooden Prince, Bartók wrote an orchestral suite from The Miraculous Mandarin's original score.

International Success

From 1918, a Vienna publishing house which worked with other leading composers like Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) took on Bartók's catalogue. Dance Suite, published in 1923, was the composer's first popular success. Bartók toured as a concert pianist in the 1920s and '30s. He often wrote pieces that he himself would premiere. This was the case with the First Piano Concerto (1926), his Out of Doors suite (1926), the Nine Little Pieces (1926), and the Second Piano Concerto (1931). He also wrote works for other people, notably Contrasts for the famous American clarinet player and band leader Benny Goodman (1909-1996) and the Hungarian violinist József Szigeti (1892-1973).

By 1934, Bartók had left his teaching post so that he could spend more time composing and collecting traditional songs. By now, Bartók was widely considered "one of the world's most knowledgeable ethnomusicologists" (Schinberg, 657). He travelled through Central Europe, the Balkans, Anatolia, and even North Africa collecting material for his research into authentic traditional folk music. Authenticity was not so easy to find, but it was essential to Bartók's mission, which was to create something new from the old. He once said: "We must isolate the very ancient, for this is the only way of identifying the really new" (Steen, 721).

The composer's reputation was growing abroad thanks to his concert tours across Europe and in the USSR. 1934 saw the premiere in London of the Cantata profana (subtitled The Nine Enchanted Stags), which was based on a traditional Romanian hunting carol or colinda. The work, both text and music, was written by Bartók four years before as a celebration of nations working together. Sadly, certain European leaders were not listening to the message of the musicians, and the Second World War (1939-45) broke out with the invasion of Poland in 1939. Both Germany and the USSR were fast moving in on Central Europe, and Hungary lay in their path. After the death of his mother in 1939, Bartók decided to leave for the safety of the United States, a place he was not unfamiliar with, having performed in two concert tours there already.

Musical Style & Innovations

Despite his love of traditional music, Bartók was always interested in new ideas. In the 1930s, he began experimenting with the use of mathematics in composition. Very often Bartók's works carry an exact timing and present a certain symmetry. For example, "five movements are arranged symmetrically in an ABCBA pattern, the 'A' and 'B' sections being transformed reflections of each other, not literal repeats" (Sadie, 343). The Classical Music Encyclopedia describes Bartók's musical style as "strongly rhythmic, percussive, sharply dissonant music that…earned him a leading position among the European avant-garde" (342).

Another area of exploration was achieving different sounds from percussion instruments. For example, there is a moment in the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion when the percussionist is required to strike the edge of a cymbal using a knife blade. Bartók was also fond of the rarely used cimbalom. Other peculiarities indulged in by the composer included Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, an orchestral work composed in 1936, which was unusually presented in that Bartók "divided the strings into two chamber groups placed on either side of a piano, harp, celeste and percussion section" (Wade-Matthews, 51). This work is often regarded as Bartók's masterpiece.

In the other direction, Bartók, along with the Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975), helped revive interest in music for string quartets, which had gone out of fashion in the 19th century. Bartók's First String Quartet was composed in 1908 and displays an influence from the French composer Claude Debussy (1862-1918). In all, Bartók composed six string quartets.

Personal Life & Views

In 1910, Bartók married Márta Ziegler, one of his pupils, who was 16 at the time. The couple had a son, born in 1910. The composer divorced Márta and married again in 1923. His second wife, Ditta Pásztory, was also a former pupil; the couple had a son in 1924. As a Hungarian nationalist with a strong desire to protect his culture as distinct from the Austrian half of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Bartók very often wore national dress and was dead against his children learning German (the language of the Austrian half of the empire). This anti-Germanic sentiment only grew in the 1930s as a result of the increasing threat of Nazi Germany and such measures as the 1935 Nuremberg Laws which imposed classifications and restrictions on Jewish people. Bartók refused to perform in Germany and would not permit the Nazi regime, which he described as "a system of robbery and murder" (Schonberg, 664), to broadcast his work. Bartók also left his Austrian publisher since it now sent out questionnaires to determine the race and religion of the composers on its books. Bartók switched to Boosey and Hawkes based in Britain.

Important Works

The most famous works by Béla Bartók include:

2 violin concertos (1938 & 1945)

3 piano concertos (1926, 1931, & 1945)

6 string quartets (1908, 1917, 1927, 1928, 1934 & 1939)

Duke Bluebeard's Castle (A kékszakállú herceg vára) – opera (1911-18)

The Wooden Prince (A fából faragott királyfi) – ballet (1918)

The Miraculous Mandarin (A csodálatos mandarin) – pantomime ballet (1919)

Dance Suite (Táncszvit) - orchestral work (1923)

Mikrokosmos - 153 piano works (1926-39)

Village Scenes - choral music (1930)

Cantata profana - choral music (1930)

Székely Songs (1932)

Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1936)

Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion (1937)

Contrasts – work for clarinet, violin and piano (1938)

Divertimento for Strings – orchestra work (1939)

Concerto for Orchestra (1943)

Death & Legacy

In his new life in the United States, Bartók lived outside New York in an apartment in Forest Hills. Here, for the last five years of his life, he composed, performed, and conducted yet more research into folk music, this time under the auspices of Columbia University. Even if he had escaped the woes of wartorn Europe, these were troubled times personally. He was homesick, beset with health problems, and had money worries as the concert engagements dried up.

12 Great Composers

The composer discovered he had leukemia in 1943, and so his last public performance, one supported by the New York Philharmonic, was in January that year. As so often with artists, though, adversity in his private life was coupled with triumph in his public one. Bartók's Concerto for Orchestra was premiered in Boston in 1943, a performance conducted by Serge Koussevitsky (1874-1951). This work is often cited as Bartók's most popular. In the same year, he composed the Violin Sonata, which was commissioned by the virtuoso Yehudi Menuhin (1916-1999). One of Bartók's final pieces was the Third Piano Concerto, which he dedicated to his wife. Béla Bartók died in New York on 26 September 1945. Amongst his last words were: "The trouble is that I have to go with so much still to say" (Schonberg, 666).

Bartók, apart from his lasting popularity and contribution to the promotion of traditional Hungarian music, also influenced later musicians, notably the Hungarian composer György Ligeti and the Polish composer Witold Lutosławski (1913-94), who dedicated his Funeral Music of 1948 to Bartók. Mikrokosmos, the collection of 153 piano pieces arranged by Bartók, became a standard teaching book. A collection of Bartók's studies of folk music was published in 1976 under the title Béla Bartók Essays.