Camille Desmoulins (1760-1794) was one of the most prominent journalists during the French Revolution (1789-1799). A fervent republican, he played an important role in the Storming of the Bastille, when he called the people to arms. Although initially a radical, Desmoulins criticized the excessive violence of the Reign of Terror, leading to his execution on 5 April 1794.

Pre-Revolutionary Life

Lucie-Simplice-Camille-Benoist Desmoulins was born on 2 March 1760 in Guise, a town in the northern French province of Picardy. The eldest of five children, he was born to Jean-Benoit-Nicholas Desmoulins, a lieutenant-general of the bailiwick of Guise, and his wife, Marie-Madeleine Godart. Camille's father was poor, but his job as a local official had made him many powerful connections. He used one of these connections to secure a scholarship for his eldest son to the college of Louis-le-Grand in Paris.

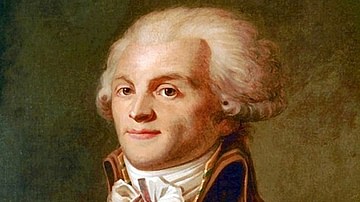

Camille began attending the school at age 14, studying law. While there, he developed a close friendship with Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794), a fellow law student from Arras. Camille became Robespierre's closest companion at Louis-le-Grand, a friendship they would later rekindle during the Revolution, despite the differences in their personalities and beliefs. Years later, Robespierre's sister Charlotte wrote: "I know that my brother loved Camille Desmoulins dearly…he often told me that Camille was perhaps one of all the prominent revolutionaries he loved the best, after our younger brother and Saint-Just" (Methley, 25).

Robespierre and Desmoulins bonded over their shared love of antiquity. It was from this passion for ancient history that the seed of republicanism grew in Desmoulins' mind, long before the Revolution began. He later explained:

The first Republicans to appear in 1789 were young men who, fed upon Cicero in the colleges, were passionately fond of liberty. We were taught at the schools of Rome and Athens and in the pride of the Republic, only to live in the despair of monarchy ... what a mad government, to think that we could be enthusiastic about the fathers of the Roman Republic without being horrified at the man-eaters of Versailles, that we could admire the past without condemning the present. (Beraud, 126)

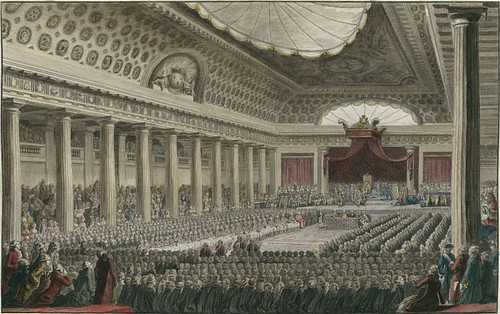

Upon graduating Louis-le-Grand, Camille was admitted to the Paris bar in 1785. However, his fear of public speaking, exacerbated by a lifelong stutter, caused him to quickly give up this vocation, deciding to pursue a career in political journalism instead. This did not pay well, and the late 1780s found Desmoulins living in an inn, regularly writing to his father to ask for money. His fortune changed in May 1789, when the Estates-General of 1789 convened in Versailles, beginning the French Revolution. He spent much of that month travelling between Versailles and Paris, observing the exciting meetings of the Third Estate and dining with eminent Third Estate leaders like Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau (1749-1791).

Desmoulins' firsthand experience of the opening days of the Revolution helped radicalize him further; he never missed a demonstration in Paris, and he became a regular at local political clubs, where he practiced giving speeches. Gradually, he overcame his nervousness about public speaking and became good enough an orator to write to his father: "Many people who hear my speeches are astonished that I have not been made a deputy [of the Third Estate], a compliment which flatters me inexpressibly" (Beraud, 137).

Bastille

While Camille Desmoulins was basking in the Revolution, King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) was looking to end it. In early July 1789, he called several regiments of foreign soldiers into the Paris Basin, which alarmed many revolutionaries. On 11 July, the king fired Jacques Necker, his popular chief royal minister who many credited with convening the Estates-General. This move caused panic in Paris, as many saw it as a prelude to a counter-revolutionary attack.

Around noon on 12 July, Desmoulins leaped on a table at the Café du Foy in the garden of the Palais Royal. Seizing the attention of the gathered throngs of people, he delivered an impassioned speech; in the excitement of the moment, his stutter was lost:

Citizens! There is not a moment to be lost. I come from Versailles. Necker has been dismissed, and his dismissal is the signal for another St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre of all patriots. Tonight, the Swiss and German battalions will leave the Champ de Mars to kill us. We must secure arms and wear rosettes so that we can recognize each other. (Beraurd, 135)

At this, he plucked a leaf from an overhead chestnut tree and stuck it in his hat. Brandishing a pair of pistols, he proclaimed,

To arms, to arms, and let us all take the green cockade, the color of hope… for me, I would rather die than submit to servitude. (Schama, 382)

It was truly the speech of a lifetime. Desmoulins' words lit the powder keg of the crowd which took to the streets, raiding armories for their weapons and showering stones upon royal troops. The various riots throughout the city climaxed on 14 July with the Storming of the Bastille, a watershed moment in French history. Throughout it all, many Parisians wore the green cockade invented by Desmoulins. Once it was discovered that green was already the livery of Comte d'Artois, the king's conservative brother, red and blue, the colors of Paris, were chosen to represent the Revolution instead. Desmoulins later described these colors' significance: "red, representing the blood to be shed for freedom, blue for the celestial constitution soon to come" (Schama, 387).

When the Bastille fell, the king relented. He withdrew the soldiers, reinstated Necker, and ceded more authority to the National Constituent Assembly. The Revolution was secured, and Desmoulins found himself an overnight celebrity. Two months earlier, he had written a pamphlet entitled La France Libre (France Liberated) but had been unable to find publication; on 18 July, it was published, to extraordinary success. An examination of the rights of the king, the aristocracy, and the clergy, Desmoulins' pamphlet was ahead of its time, in that it was an explicit call to republicanism years before the Revolution trended in that direction. It won him the friendship of Mirabeau himself, greatly increasing the young writer's prestige. Amidst this resounding success, Desmoulins wrote to his father:

I have made a name for myself and people now say: "a Desmoulins pamphlet" not "a pamphlet by an author called Desmoulins". Several women have invited me to their receptions, but nothing could give me more pleasure than that moment on 12 July when I was, I shall say, not applauded by 10,000 people but smothered by their tearful embraces. (Beraud, 138)

Journalism

In September 1789, Desmoulins leaned into his reputation as a radical pamphleteer. His Discours de la lanterne aux Parisiens was an ode to revolutionary violence, as it was written from the point of view of the lamppost at the Place de Grève, which was often used by revolutionary rioters as a makeshift gallows where counter-revolutionary enemies were lynched. It featured an epigraph from the Gospel of John: "Everyone who does evil hates the light" (John 3:20). This publication earned Desmoulins a reputation for inciting violence, along with the nickname "the Lantern Prosecutor".

It was not until 28 November 1789, however, that Desmoulins launched the first issue of the newspaper that would cement his role as one of the Revolution's leading figures. The paper, Les Révolutions de France et de Brabant ("The revolutions of France and Brabant") was immediately successful and remained so until its final issue in July 1791. The first issue prematurely proclaimed the Revolution to have succeeded, announcing:

All is consummated; the king is in the Louvre, the National Assembly in the Tuileries ... the patriots are victorious ... we can say to the National Assembly, "You have no more enemies, no more contradictors, no more vetoes to fear. All that is left is for you to govern France, to make her happy." (Beraud, 140)

Desmoulins' paper appeared every Saturday, usually consisting of three pages of articles and one illustration. It won a wide audience; some liked the shocking yet patriotic subject matter, while wider-read audiences appreciated Desmoulins' eloquent writing style and his frequent allusions to antiquity. The paper often became the subject of controversy, especially as Desmoulins continued promoting republicanism; he frequently sparred with pro-royalist newspapers, one of which referred to him as "l'ânon des moulins" ("jackass of the windmills"), a play on his surname.

Desmoulins' radicalism caused his estrangement from former friends Mirabeau and Baron Malouet, who found his work distasteful; an April 1791 issue, for instance, contained a graphic illustration of nuns being flogged. Things got so bad that Malouet called for Desmoulins' arrest in July 1790, accusing him of attempting to foment insurrection; Desmoulins was saved from arrest by Robespierre, who convinced his colleagues not to charge the young journalist. By now, Desmoulins was making other friends, closer to his own radical ideology. Early in 1790, he joined the Cordeliers Club, in which he quickly became a prominent member and befriended the Club's leader, Georges Danton (1759-1794). With the backing of the Cordeliers, Desmoulins continued his attacks against royalist and centrist figures.

In June 1791, Louis XVI's attempted escape from France, dubbed the Flight to Varennes, failed. In response, Desmoulins called for the king's immediate deposition and the creation of a republic. On 17 July, he and the Cordeliers organized a demonstration on the Champ de Mars to make these demands; the demonstrators were fired on by National Guards under the command of Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. After the Champ de Mars Massacre, the empowered constitutional monarchists issued a warrant for Desmoulins' arrest, forcing him to go into hiding. It was not until he was amnestied in September that he reemerged.

Marriage

On 29 December 1790, Desmoulins married Lucile Duplessis, who he had been courting for many years. Witnesses of the wedding included prominent revolutionaries Jacques-Pierre Brissot (1754-1793) and Robespierre; according to some sources, Robespierre had briefly considered marrying Lucile's sister. The officiator of the wedding was Desmoulins' old headmaster at Louis-le-Grand. Camille and Lucile had one child, Horace-Camille, born on 6 July 1792; Robespierre was named godfather. By all accounts, Camille was a loving husband and father.

In August 1792, Desmoulins' republican dreams were realized. Together with his friend Danton, he helped organize the insurrection of 10 August which captured the Paris Commune and led to the Storming of the Tuileries Palace, which toppled the monarchy. Danton became the city's minister of justice, and Desmoulins briefly served as his secretary. The next month, the First French Republic was officially proclaimed, and Desmoulins was elected to the new government, the National Convention.

Feud with Brissot

Desmoulins found himself caught up in a bitter struggle between two rival Jacobin factions: the moderate Girondins, led by Brissot, and the extremist Mountain, increasingly dominated by Robespierre. Desmoulins, who had been gravitating toward the Mountain, wholeheartedly sided with them after a bitter argument with Brissot over things Desmoulins had said in his paper. Desmoulins responded with a pamphlet entitled Brissot Unmasked, in which he accused his former friend of having coaxed France into the Revolutionary Wars, which were going disastrously at the time, and of having been a police spy for the old regime.

Encouraged by Robespierre, Desmoulins kept up his attacks, releasing another publication in May 1793 which accused all of the Girondins of being foreign agents who were actively working toward the Revolution's destruction. Like most of Desmoulins' works, this one was widely circulated and likely contributed to the Insurrection of 2 June 1793, in which thousands of sans-culottes swarmed the National Convention, demanding the arrests of the traitorous Girondins. This was achieved, and the fall of the Girondins allowed for the dominance of the Mountain and the ensuing Reign of Terror.

During the Terror, Desmoulins distanced himself from the Mountain. He spoke less frequently on their behalf on the Convention floor, becoming one of the few voices to argue for clemency for the hundreds of thousands of 'suspects' being arrested across France. He became troubled by his perceived role in bringing the Terror into existence and was haunted that his actions led to the deaths of his former friends; on 30 October 1793, when Brissot and the Girondins were condemned to death, Desmoulins was heard to exclaim, "My God, my God! It is I who kills them!" (Scurr, 299).

Le Vieux Cordelier

Perhaps it was this guilt that mellowed Desmoulins, turning the former radical into a moderate. Together with Danton, he became a leader in the new moderate group, the Indulgents, who advocated for an end to the war and the scaling back of the Terror. The Indulgents' natural foes were the Hébertists, an 'ultra-revolutionary' group led by Jacques-René Hébert that wanted to intensify the Terror. The Hébertists had usurped the Cordeliers Club, which Danton and Desmoulins had once controlled.

In response, Desmoulins created a new paper on 5 December, entitled Le Vieux Cordelier ("The Old Cordelier") to remind its readers about an earlier, more hopeful era of the Revolution. Robespierre, who also had a vested interest in the destruction of the Hébertists, gave his blessing for the paper and initially preapproved each issue. The paper, issuing scathing attacks against the Hébertists, was well-received and hindered the Hébertists' influence for a while.

Falling victim to his own vanity, Desmoulins did not stop there. Issues 3 and 4 of the paper, published without Robespierre's approval, were attacks against the Mountain regime. The paper criticized the authority of the Revolutionary Tribunal and effectively called for an end to the Terror. Naturally, this offended many powerful Mountain leaders who demanded Desmoulins' expulsion from the Jacobin Club. Desmoulins' friends could tell he was overstepping himself, with one of them warning, "Camille, you seem very close to the guillotine" (Scurr, 299).

Desmoulins, confident in the protection provided by his friendship with Robespierre, dismissed these warnings, sealing his own fate. Indeed, Robespierre tried to protect Desmoulins at first. At a meeting in the Jacobin Club, he shrugged Desmoulins off as an unthinking youth who was led astray by bad company. He said that Desmoulins could be forgiven if his newspapers were burnt. Hotheaded as ever, Desmoulins was having none of it; he stood and, quoting Rousseau, cried out, "Burning is no answer!" Robespierre, enraged by this public challenge to his authority, accused Desmoulins of having aristocratic intentions. Their heated argument continued until Danton pulled Desmoulins away. Not long after, Desmoulins was expelled from the Jacobin Club on 10 January 1794.

Downfall & Execution

Desmoulins' public spat with Robespierre heralded the end for him. Despite his friendships with both Danton and Desmoulins, it soon became clear to Robespierre that the Indulgents were roadblocks to his goals. On the night of 29 March, Danton, Desmoulins, and 13 of their allies were arrested. They were charged in connection to a corruption scandal surrounding the French East India Company, as well as a general charge of treason.

The trial lasted from 2-4 April; Desmoulins' own cousin, chief prosecutor Antoine Fouquier-Tinville, led the prosecution. Desmoulins tried to remain as defiant as the confident Danton; when asked to state his age, Desmoulins replied, "33, the same age as that sans-culotte Jesus Christ" (Scurr, 314). When the Revolutionary Tribunal denied the Indulgents the right to speak in their own defense, Desmoulins rose and dramatically tore up the speech he had prepared.

Yet, when the sentence of death was handed down, Desmoulins lost his cool. He stayed frozen to his seat and had to be pried up by soldiers, who then hauled him off to prison. Once there, he received news that his wife Lucile had also been arrested, sending him into a fit of tears. "Will they kill my wife too?" he asked over and over as Danton tried to comfort him. He calmed down enough to write his wife a goodbye letter:

My Lucile, despite my torment I believe there is a God, my blood will efface my faults, I will see you again one day, O my Lucile ... is the death which will deliver me from the spectacle of so many crimes such a misfortune? Adieu, Loulou, adieu my life, my soul, my divinity on earth ... I feel the river banks of my life receding before me, I see you again Lucile, I see my arms locked around you, my tied hands embracing you, my severed head resting on you. I am going to die ... (Schama, 820)

In the morning, he again lost his composure, tearing his clothes and pleading with the crowd as the tumbril rolled through the streets, bearing the condemned to the guillotine. Camille Desmoulins, only 33, was the third of his group of 15 to be executed; Danton died last, covered in the blood of his best friends.

Lucile Desmoulins did not long outlive her husband. When he had first been arrested, Lucile had written to Robespierre to beg for Camille's life, asking the Jacobin leader to think of her son, who was Robespierre's godson. When Robespierre did not respond, Lucile allegedly met with Camille's friends, conspiring with them to free her husband from prison. When one of them betrayed her to the authorities, Lucile herself was arrested and was guillotined a week after her husband on 13 April 1794, aged only 24. Her last letter to her mother reads: "Goodnight, dear Maman. A tear falls from my eyes; it is for you. I am going to sleep in the tranquility of innocence." The Desmoulins' son, Horace, was thereafter raised by Lucile's mother. He migrated to Haiti in 1817 where he died in 1824.