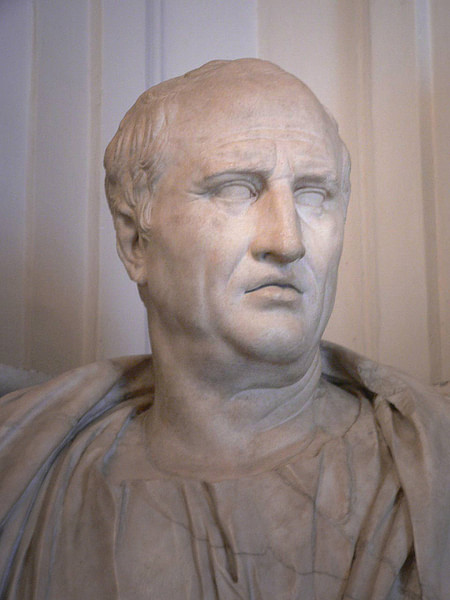

Marcus Tullius Cicero was a Roman orator, statesman, and writer. He was born on 6 January 106 BCE at either Arpinum or Sora, 70 miles south-east of Rome, in the Volscian mountains. His father was an affluent eques, and the family was distantly related to Gaius Marius. He is not to be confused with his son (of the same name) or Quintus Tullius Cicero (his younger brother). Cicero died on 7 December 43 BCE, trying to escape Rome by sea.

Early Life & Political Career

Cicero was sent to Rome to study law under the Scaevolas, who were the equivalent Ciceros of their day, and he also studied philosophy under Philo, who had been head of the Academy at Athens and also the stoic Diodotus. However, Cicero's early life was not one that was sheltered behind books and learning, and at the age of 17, he served in the Social War under Pompey the Great's father. It was during this period of political upheaval in Rome, the 80s BCE, that Cicero finished his formal education.

However, that is not to say that Cicero stopped his learnings. In 79 BCE he left Rome for two years abroad, with the aim of improving his health and studying further. In Athens, he was taught by masterful Greek rhetoricians and philosophers, and it was in Athens that he met another Roman student, Titus Pomponius Atticus. Atticus went on to be Cicero's lifelong friend and correspondent. Whilst in Rhodes Cicero went to the famous Posidonius. It was during this time that Cicero married his first wife, Terentia, and after he had returned to Rome in 77 BCE, he was voted quaestor at the minimum age of 30. Things were seemingly progressing quickly, but after having spent his quaestorship at Lilybaeum, he never gladly left Rome again. As such his refusal of provincial governorships led to Cicero concentrating on legal work, through which he prospered both monetarily and politically. A good example of this is the In Verrem, this speech has a message of interest that is relevant to current issues of cultural heritage and war. In 69 BCE Cicero was aedile, and in 66 BCE Cicero became praetor, again, at the minimum age, which was 40.

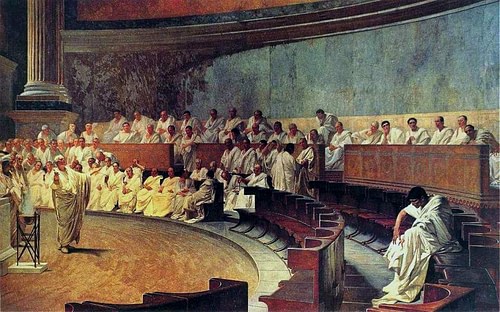

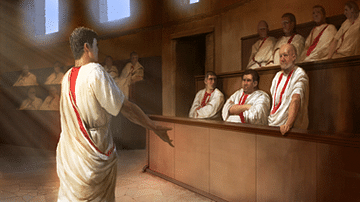

Between 66 and 63 BCE Cicero's political views became more conservative, especially in contrast to the social reforms being proposed by Julius Caesar, Gaius Antonius, and Catiline. Cicero's success is born by the fact that he received the consulship of 63-62 BCE, once again, at the minimum age (42), and that he was consul prior, the consul who had won by the most votes, and further to this, he was also a novus homo. It was during this time that Cicero successfully exposed the Catilinian revolution, and under the power of the Senatus Consultum Ultimum put to death the revolutionaries who had survived up until that point. This led to Marcus Cato calling Cicero pater patriae, 'father of his country'.

Exile & Return to Rome

It was at the end of 62 BCE that Cicero first kindled Clodius' hatred against him; after Cicero's evidence had foiled Clodius' alibi in a case which accused him of dressing as a woman to gain entrance to the Bona Dea, a mystery, female-only event. This case came back to haunt Cicero in 58 BCE, when Clodius, having been voted tribune of the people, introduced a retrospective law that outlawed any Roman who had put a Roman citizen to death without a trial. It is fairly certain that this law related specifically to Cicero's actions during the Catilinian uprising five year before when the revolutionaries had been killed without trial, due to the urgency with which the revolt needed to be put down. In March 58 BCE Cicero left Rome in exile. Any doubt over some sort of personal motive by Clodius is dispelled by the fact that he then went on to make a decree that specifically named and exiled Cicero and then confiscated his property on the Palatine Hill, which was then destroyed. However, the exile was shortlived. Pompey, aided by the tribune Milo, pushed for a law of the people that would recall Cicero; the law was passed on 4 August 57 BCE.

Cicero had never been friendly towards the first triumvirate, specifically Julius Caesar and his radicalising policies. Despite this, Caesar had always been fairly cordial to Cicero, and seemingly, when the First Triumvirate was originally founded, had made suggestions to Cicero with the possible view to include him in the alliance. It was Cicero's principles that averted any such eventuality; he was unwilling to go into any political relationship with someone whose views were so opposed to his own. In 56 BCE, this sentiment can still be seen in letters to his friends which express how his pride had been crushed after having to accept the political situation (the first triumvirate had been renewed in April 56 BCE).

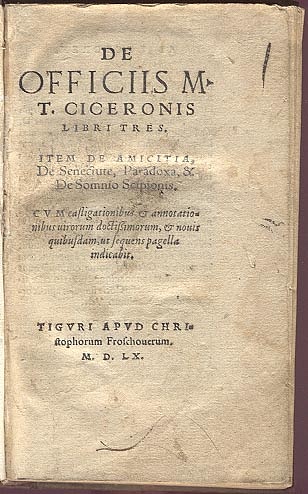

As the politics of the Roman Republic worsened in the 50s BCE Cicero turned to writing philosophy and rhetoric, perhaps as a way of escaping the situations he had to deal with. In 55 BCE Cicero wrote the De oratore, three books on rhetoric. In 54 BCE Cicero was further insulted by being bided by the triumvirs to defend those who were his enemies, Vatinus and Gabinius (the Pro Vatinius was successful but the Pro Gabinius was unsuccessful), and he was devastated when his defence of Milo, the man who had been vital in Cicero's return to Rome, failed, and Milo was sent into exile. There was only slight solace for Cicero when he was elected augur in 53 BCE.

From 51-50 BCE Cicero was under duty to govern the province of Cilicia; when he arrived back at Rome, the city was on the edge of civil war, and when it finally toppled into that abyss, Cicero left the city once more. It was only in 47 BCE when Caesar and Pompey had finally settled their differences that he thought it safe to return to the city. However, things did not exactly get better for him; this time it was for private, rather than public, reasons. In 46 BCE Cicero divorced his wife Terentia, whom he had been married to for almost 30 years and then married Publilia, who had been his ward, shortly afterwards. The next year grief struck Cicero when his daughter Tullia died, and the lack of sympathy that his second wife showed led to her also being divorced.

Later Life & Written Works

Matters were made worse for Cicero by the fact that it was becoming ever more apparent that Caesar was not going to reinstitute the republican constitution. Cicero then turned to writing, composing some of his greatest works, since his political career could not last; he had supported what was in the end a constitution that did not succeed. In 45 BCE Cicero composed the Consolatio, on the deaths of great men, and the Hortensius, which is a plea to study philosophy. A now lost panegyric to Cato was also written in this year, which Caesar himself replied to with the Anticato (again, lost). With the murder of Caesar in 44 BCE, there was once again great political upheaval in Rome, with the beginnings of the Roman Empire in the making, and it was this that eventually led to the events of Cicero's execution.

When the Second Triumvirate had come into action between Octavian, Lepidus, and Mark Antony, as a result of Cicero's propaganda against Antony in the form of his Philippics, Cicero's name was on the first list of people that Antony had put down for proscriptions. As Cicero tried to escape the inevitable, he was caught by Antony's men and boldly accepted his execution. Both his hands and head were put on display on the rostra in Rome; a grim ending to a brilliant man's life that emphasises the brutality of the politics at end of the Roman Republic.

With the death of Cicero, so began his legacy. It would be very difficult to overestimate the influence that Cicero has had on western literature and culture, and there is one story that perhaps best describes how important Cicero was seen to be, told by Harry J. Leon when discussing the dispute of the neighbouring peoples of Sora and Arpino with regards to claiming their town as Cicero's birthplace:

It is said that the rivalry between the two towns at one time became so keen that the matter had to be settled by a single combat on horseback between champions representing each of the towns. The knight of Arpino by his victory demonstrated conclusively that it was God's judgment that Cicero was a native of Arpinum and it was declared a heresy for anyone to believe otherwise. (Leon)

Whether this story is true or not, it shows just how important Cicero was seen to be, that men might fight over him. Perhaps the most direct way to appreciate Cicero's influence is through the works of his that survive. Only a few of Cicero's many works have been referred to in this definition, and there were many, including letters to friends and family, such as the Epistulae ad familiares. Due to Cicero's place in Roman society the letters act as brilliant historical and cultural documents of the period and help to give an insight into the workings of late Republican Rome outside of the context of the law court. They discuss all sorts of things, from procuring Greek art to dowries, divorces, and deaths. Unfortunately, there are no letters for the year, or the year before, Cicero's consulship.

Conclusion

Cicero was undoubtedly the greatest orator of his day, and it is credit to him that his first surviving speech was made against Hortensius, who was the greatest orator in Rome until Cicero made his name there. However, it is interesting to note that Cicero, whilst he had been a successful statesman, played no major part in the political turmoil at the end of the Republic, his legacy is very much cultural, especially the contributions that his translations of philosophy had on the development of Latin. To end, as Mrs. Blimber said in Dickens' Dombey and Son, “If I could have known Cicero, and been his friend, and talked with him in his retirement at Tusculum… I could have died contented.”