Gaius Valerius Catullus (84-54 BCE) was a Roman poet whose poems are considered to be some of the finest examples of lyric poetry from ancient Rome, despite his youth and early death. Catullus wrote in the neoteric style during the high point of Roman literature and culture, and his poems were not only read and appreciated during his lifetime but influenced such respected Augustan-era poets as Ovid, Virgil, and Horace. His surviving works include short poems, longer poems, and epigrams; 25 love poems are addressed to a woman he calls 'Lesbia'.

Early Life

Catullus was born around 84 BCE to a distinguished and wealthy family of the equestrian order in the northern Italian town of Verona. No biography of him exists, so what details are known come from the writings of others and his own poetry.

Hoping his son would benefit from the rich culture of the city, Catullus' father sent his young son to Rome. Through his poetry, it is thought that while living in Rome he became acquainted with many of the leading politicians of the time, namely Cicero (106-43 BCE), who despised his poetry, and the good friend of his father, Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE). Suetonius (c. 69 - c. 130/140 CE) in his The Twelve Caesars relays a confrontation between Caesar and Catullus. Supposedly, the poet had libeled Caesar in one of his poems. Caesar responded, claiming it was a blot on his good name, but after Catullus apologized, he was invited to dinner. Caring little for the political arena, the young poet did not enjoy his brief venture into public service (57-56 BCE) as a member of the staff of Gaius Memmius, governor of the Roman province of Bithynia.

Writing Style

He returned to Rome and devoted the remainder of his life to poetry. It was at this time that he became involved with a new breed of poets, the neoterics. Turning away from the classical epic poetry of Homer (c. 750 BCE), this new genre was based on the aesthetics of Hellenistic Alexandria and the writings of the 4th-century BCE poet Callimachus, who used colloquial language and wit, basing his poems on personal experiences. Historian Norman Cantor in his book Antiquity wrote that Catullus' poetry served as a “counterbalance” to the idealism, public-mindedness, and optimism of his contemporary Marcus Tullius Cicero. Catullus recognized mortality as an essential part of the human condition and exposed a different side of Roman life: the existence of pessimism and individualism.

Classicist Edith Hamilton in her book The Roman Way wrote that he could "turn out a charming bit of verse on whatever he pleased, his sailing boat … a dinner party, a friend's grief or what not" (108). However, he could also be as coarse and violent as anything found in literature. Catullus "pours out what he feels with a burning passion that will have nothing but the plainest expression" (108). To illustrate her point, she quotes one of his poems written to his beloved Lesbia:

Dearest, my life, my own, you say our love is forever, what is between us shall be joy of love without end. (112)

While he spent much of his life in Rome, eventually owning a small villa in the Roman suburb of Tibur, many of his poems are set in Verona. While he avoided public service and involvement in the political arena - like many fellow neoterics - many of his poems still reflect the character of the Roman Republic, its politics, social life, and culture. His poems represent a people more interested in their private life than public responsibility.

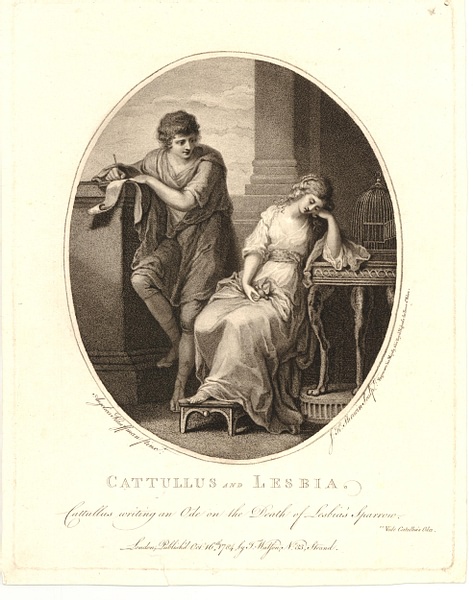

Lesbia

After his arrival in Rome, he fell in love with a young woman assumed to be Clodia Metelli, the sister of Cicero's enemy, Publius Clodius Pulcher (93-52 BCE), and wife of a deceased Roman senator. Although she is accused of having a scandalous reputation, the details of his relationship with her, and whether or not it was fully reciprocal, are unknown. Supposedly, she is the Lesbia of his love poems - a homage paid to the Greek poet Sappho (c. 620-570 BCE) from the island of Lesbos.

Hamilton wrote that Catullus saw nothing in his universe but Lesbia and was able to speak with simplicity because he felt nothing that was not simple. Cicero felt differently, hating her, calling her the "Medea of Palatine" and attacking her (she was supportive of her brother's politics) in many of his speeches. Catullus wrote 25 poems dedicated to his 'Lesbia'. One of these poems is entitled My Sweetest Lesbia and is an expression of his profound love for her:

My sweetest Lesbia, let us live and love

And though the sager sort our deeds reprove

Let us not weigh them. Heaven's great lamps do die

Into their west, and straight again revive,

But soon, as once set is our little light,

Then must we sleep one ever during night

He concludes the poem by saying:

And, Lesbia, close up thou my little light,

And, crown with love my ever-during night. (quoted in Garrigue, 106)

Works

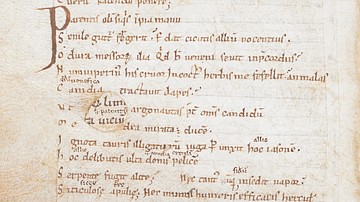

The poems of Catullus have survived despite almost being lost during the Middle Ages. One forgotten manuscript survived, was found, copied, copied again, and then lost again. Finally, it was recovered and compiled into the present collection. Three “original” copies exist – one in Paris, one in Rome, and one in London. However, poor copying together with the terrible condition of the original manuscript have left several poems mutilated and incomplete. Arguments still persist on the exact number of poems Catullus wrote, estimates ranging from 113 to 116. There is speculation at least five poems have been completely lost. Some poems are incomplete; 14 are believed to have gaps of at least one to eight lines. Similarly, fragments of some poems have been arbitrarily attached to other poems. And, some longer poem might have even been split into two. Others, attributed to the young poet, may not actually be his - 18, 19, and 20 for example.

His shorter poems vary from 5 to 25 lines while others are longer, ranging from 48 to over 400 lines. There are even epigrams of 2-12 lines. Some are quite moving while others are considered obscene. The first 60 poems are short, addressed to his friends, lovers, and even enemies. While some of these are friendly and passionate, others could be abusive:

Listen up girl, with nose not really petite,

feet less than handsome,

and eyes murky.

Your fingers are not so slender

and your mouth drips slobber.

And did you not know that your

tongue is quite grotesque?(Eleven Poems, Poem 43)

The middle eight (Poem 61-68) are deemed Alexandrian or Greek in their style; four are elegies. One is devoted to the marriage of Peleus and the sea goddess Thetis, parents of the war hero Achilles known from Greek mythology, while another speaks of the early death of his brother.

The remaining poems (69-116) are epigrams about love and grief. In one poem, it is apparent that his cherished Lesbia has rejected him:

Lesbia, I am mad:

My brain is entirely warped

by this project of adoring

and having you

and now it flies into fits

of hatred at the mere thought

of you(Eleven Poems, Poem 75)

In one of his best-known poems, he speaks of his continued torment:

I hate and love. If you were to ask how

I got this way, I'd have no answer;

But since I can recall, I have suffered

I have felt this torment(Eleven Poems, Poem 85)

Legacy

The cause and exact date of his death are unknown, but the 4th-century CE theologian and historian Saint Jerome maintains that the young poet died around 54 BCE at the age of 30. Although it was almost lost, his poetry has survived and influenced many of the poets that followed him. His popularity continued into the Middle Ages and English Renaissance. Hamilton sums up the beauty of his poems, comparing his poems to the sonnets of William Shakespeare, writing that he was able to put a lover's rapture into words. "In his life as in his love he was the quintessential lover, he died young." (115)