Cleopatra VII (69-30 BCE, reign 51-30 BCE) was the last ruler of Egypt before it was annexed as a province of Rome. Arguably the most famous Egyptian queen, Cleopatra was ethnically Greek as a member of the Macedonian Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 BCE), which ruled Egypt after the death of Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE), but she was culturally Egyptian and presented herself as an Egyptian queen.

She is probably best known for her love affair with the Roman general and statesman Mark Antony (83-30 BCE), as well as her earlier affair with Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE), but was a powerful queen before her interaction with either and a much stronger monarch than any of the later rulers of the Ptolemaic Dynasty.

Cleopatra was fluent in a number of languages, was reported to have been extremely charming, and was an effective diplomat and administrator. Her involvement with both Caesar and Mark Antony came about after she had already successfully ruled and steered Ptolemaic Egypt through a difficult period.

Her affair with Antony brought her into direct conflict with Octavian (later known as Augustus, reign 27 BCE to 14 CE), who was Antony's brother-in-law. Octavian would defeat Cleopatra and Antony in the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, ending her reign. She and Antony would then both commit suicide the following year, and Octavian would found the Roman Empire and relegate Cleopatra to a minor chapter in Rome's past. Scholar Stacy Schiff comments:

The rewriting of history began almost immediately. Not only did Mark Antony disappear from the [official] record, but Actium wondrously transformed itself into a major engagement, a resounding victory, a historical turning point. It went from an end to a beginning. Augustus had rescued the country from great peril.

(297)

The Roman historians seized on the concept of the seductive woman from the East who had threatened Rome and paid the price. This image of Cleopatra has, unfortunately, remained through the intervening centuries, and only in the last century have scholarly attempts been made to portray her in a more realistic and flattering light.

Youth & Succession

In June of 323 BCE, Alexander the Great died, and his vast empire was divided among his generals in the War of the Diadochi. One of these generals was Ptolemy I Soter (reign 323-282 BCE), a fellow Macedonian, who would found the Ptolemaic Dynasty in ancient Egypt.

The Ptolemaic line, of Macedonian-Greek ethnicity, would continue to rule Egypt until the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BCE, when it was taken by Rome. Ptolemy I, Ptolemy II (reign 285-246 BCE), and Ptolemy III (reign 246-222 BCE) governed Egypt well, but after them, their successors ruled poorly until Cleopatra came to the throne. In fact, the difficulties she had to overcome were primarily the legacy of her predecessors.

Cleopatra VII Philopator was born in 69 BCE and ruled jointly with her father, Ptolemy XII Auletes. When she was 18 years old, her father died, leaving her the throne. Because Egyptian tradition held that a woman needed a male consort to reign, her 12-year-old brother, Ptolemy XIII, was ceremonially married to her. Cleopatra soon dropped his name from all official documents, however, and ruled alone.

The Ptolemies, insisting on Macedonian-Greek superiority, had ruled in Egypt for centuries without ever learning the Egyptian language or fully embracing the customs. Cleopatra, however, was fluent in Egyptian, eloquent in her native Greek, and proficient in other languages as well. Because of this, she was able to communicate easily with diplomats from other countries without the need of a translator and, shortly after assuming the throne, without bothering to hear the counsel of her advisors on matters of state. Schiff notes how "Cleopatra had the gift of languages and glided easily among them" (160). Plutarch, from whose works Schiff draws this observation, writes:

It was a pleasure merely to hear the sound of her voice, with which, like an instrument of many strings, she could pass from one language to another; so that there were few of the barbarian nations that she answered by an interpreter.

(Lives, Antony and Cleopatra, Ch. 8)

Her habit of making decisions and acting on them without the counsel of the members of her court upset some of the high-ranking officials. One example of this was when Roman mercenary lieutenants employed by the Ptolemaic crown murdered the sons of the Roman governor of Syria to prevent them from requesting her assistance. She immediately arrested the lieutenants responsible and turned them over to the aggrieved father for punishment.

In spite of her many achievements, her court was not pleased with her independent attitude. In 48 BCE, her chief advisor, Pothinus, along with another, Theodotus of Chios, and the General Achillas, overthrew her and placed Ptolemy XIII on the throne, believing him to be easier to control than his sister. Cleopatra and her half-sister, Arsinoë IV, fled to Thebaid for safety.

Pompey, Caesar & The Coming of Rome

At about this same time, the Roman general and politician, Pompey the Great, was defeated by Julius Caesar at the Battle of Pharsalus. Pompey was the state-appointed guardian over the younger Ptolemy children, and on his campaigns, he had spent considerable time in Egypt. Believing he would be welcomed by friends, Pompey fled from Pharsalus to Egypt, but instead of finding sanctuary, he was murdered under the gaze of Ptolemy XIII as he came on shore at Alexandria.

Caesar's army was numerically inferior to Pompey's, and it was believed that Caesar's stunning victory meant that the gods favored him over Pompey. Further, it seemed to make more sense to Ptolemy XIII's advisor, Pothinus, to align the young king with the future of Rome rather than the past.

Upon arriving in Egypt with his legions, in pursuit of Pompey, Caesar was allegedly outraged that Pompey had been killed, declared martial law, and set himself up in the royal palace. Ptolemy XIII fled to Pelusium with his court. Caesar, however, was not about to let the young ruler slip away to foment trouble and had him brought back to Alexandria.

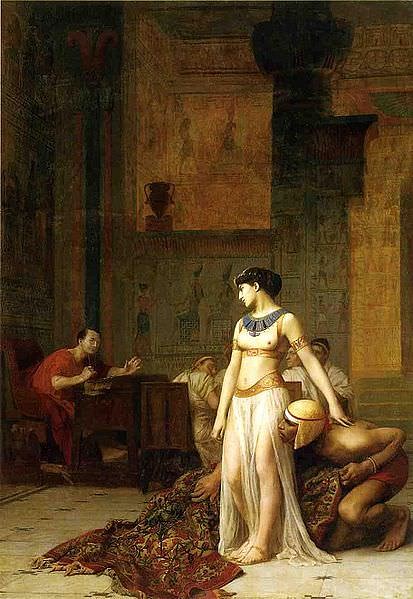

Cleopatra was still in exile and knew there was no way she could simply walk into the palace unmolested. Recognizing in Caesar her chance to regain power, she is said to have had herself rolled in a rug, ostensibly a gift for the Roman general, and carried through the enemy lines. Plutarch tells the story:

Cleopatra, taking only one of her friends with her (Apollodorus the Sicilian), embarked in a small boat and landed at the palace when it was already getting dark. Since there seemed to be no other way of getting in unobserved, she stretched herself out at full length inside a sleeping bag and Apollodorus, after tying up the bag, carried it indoors to Caesar. This little trick of Cleopatra's, which first showed her provocative impudence, is said to have been the first thing about her which captivated Caesar.

(Lives, Caesar, Ch. 49)

She and Caesar seemed to strike up an instant affinity for each other, and by the next morning, when Ptolemy XIII arrived to meet with Caesar, Cleopatra and Caesar were already lovers. The young pharaoh was outraged.

Cleopatra & Julius Caesar

Ptolemy XIII turned to his general, Achillas, for support, and war broke out in Alexandria between Caesar's legions and the Egyptian army. Caesar and Cleopatra were besieged in the royal palace for six months until Roman reinforcements were able to arrive and break the Egyptian lines. It is at this time, according to some historians, that the great Library of Alexandria was accidentally burned, though this claim has been challenged.

Before the Roman victory over Ptolemy XIII, however, Cleopatra's half-sister, Arsinoë, who had returned with her, fled the palace for Achillas' camp and had herself proclaimed queen in Cleopatra's place. Ptolemy XIII drowned in the Nile, attempting to escape after the battle, and the other leaders of the coup against Cleopatra were killed in battle or shortly afterwards.

Arsinoë was captured and sent to Rome in defeat but was spared her life by Caesar, who exiled her to live in the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, where she would remain until 41 BCE, when, at Cleopatra's urging, Mark Antony had her executed.

Cleopatra, now the sole ruler, traveled through Egypt with Caesar in great style and was hailed by her subjects as pharaoh. She gave birth to a son, Ptolemy Caesar (known as Caesarion), in June of 47 BCE and proclaimed him her heir. Caesar himself was content with Cleopatra ruling Egypt as the two of them found in each other the same kind of stratagem and intelligence, bonding them together with mutual respect.

In 46 BCE, Caesar returned to Rome and, shortly after, brought Cleopatra, their son, and her entire entourage to live there. He openly acknowledged Caesarion as his son (though not his heir) and Cleopatra as his consort. As Caesar was already married to Calpurnia at this time, and the Roman laws against bigamy were strictly adhered to, many members of the Roman Senate, as well as the public, were upset by Caesar's actions. Cleopatra's famous gifts of flattery failed to make the situation any better, and Cicero (106-43 BCE) was especially outraged as he made clear in a letter from 45 BCE:

I detest the Queen. For all the presents she promised were things of a learned kind, and consistent with my character, such as I could proclaim on the housetops...and the insolence of the Queen herself when she was living in Caesar's trans-Tiberine villa, the recollection of it is painful to me.

(Lewis, 118)

Whatever Cicero or the others thought of Cleopatra or her relationship with Caesar, it did not seem to have mattered to either of them. They continued to appear in public together even though propriety suggested they keep a lower profile.

Cleopatra & Mark Antony

After the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE, Cleopatra fled Rome with Caesarion and returned to Alexandria. Caesar's right-hand man, Mark Antony, joined with his grandnephew Octavian and friend Lepidus to pursue and defeat the conspirators who had murdered Caesar. After the Battle of Phillipi, at which the forces of Antony and Octavian defeated those of Brutus and Cassius, Antony emerged as ruler of the eastern provinces, including Egypt, while Octavian held the west.

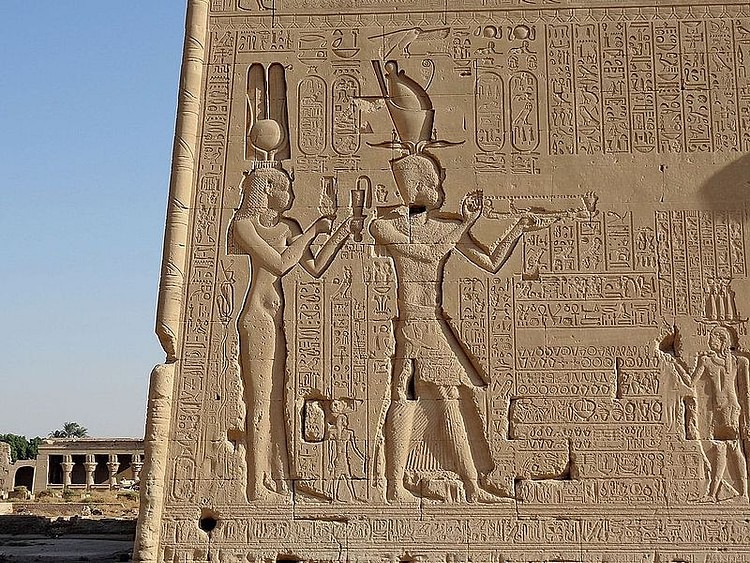

In 41 BCE, Cleopatra was summoned to appear before Antony in Tarsus to answer charges that she had given aid to Brutus and Cassius. Cleopatra delayed in coming and then delayed further in complying with Antony's summons, making it clear that, as Queen of Egypt, she would come in her own time when she saw fit. Egypt was, at this time, teetering on the edge of economic chaos, but, even so, Cleopatra made sure to present herself as a true sovereign, appearing in luxury on her barge, dressed as Aphrodite:

She came sailing up the river Cydnus in a barge with gilded stern and outspread sails of purple, while oars of silver beat time to the music of flutes and fifes and harps. She herself lay all along, under a canopy of cloth of gold, dressed as Venus in a picture, and beautiful young boys, like painted Cupids, stood on each side to fan her. Her maids were dressed like Sea Nymphs and Graces, some steering at the rudder, some working at the ropes...perfumes diffused themselves from the vessel to the shore, which was covered with multitudes, part following the galley up the river on either bank, part running out of the city to see the sight. The market place was quite emptied, and Antony at last was left alone sitting upon the tribunal while the word went, through all the multitude, that Venus was come to feast with Bacchus for the common good of Asia.

(Plutarch, Life of Marcus Antonius, Ch. 7)

Mark Antony and Cleopatra instantly became lovers and would remain so for the next ten years. She would bear him three children – Cleopatra Selene II, Alexander Helios, and Ptolemy Philadelphus – and he considered her his wife, even though he was married, first, to Fulvia and then to Octavia, the sister of Octavian. He eventually divorced Octavia to marry Cleopatra legally.

Was Cleopatra Egyptian or Greek?

Mark Antony's relationship with Cleopatra, as with her earlier affair with Julius Caesar, was criticized by Roman writers who characterized her as a "wily temptress of the East," and this has contributed to the ongoing debate on whether Cleopatra was Egyptian or Greek.

Scholar Barbara Waterson notes, "The racial typing of the earliest Egyptian is a vexed question" (13), and this question is not answered any easier by the time of Cleopatra VII, as it seems that "to be an Egyptian" meant speaking the language, adhering to the customs, honoring the gods, and living in Egypt.

The people now known as "ancient Egyptians" were racially diverse and, as Watterson notes, "the racial origins of the Egyptians is the subject of argument" (13) as they were united more by a common worldview, religion, and culture than ethnicity. According to this definition, Cleopatra VII was an Egyptian. Schiff, however, notes:

The young woman holed up with Julius Caesar in the besieged palace of Alexandria...was, as nearly as can be ascertained on all sides, a Macedonian aristocrat. Her name, like her heritage, was entirely and proudly Macedonian; "Cleopatra" means "Glory of Her Fatherland" in Greek.

(23)

Scholar Sally Ann Ashton, however, points out that, whatever Cleopatra's ethnicity, she chose to present herself as Egyptian:

It is probably no coincidence that the later, more powerful and independent queens sought to present themselves as Egyptian rather than Hellenistic Greek monarchs, because Egypt had already proved itself able to accept a female pharaoh and the religion allowed a greater autonomy than did the Greek tradition.

(114)

Arguments over whether Cleopatra VII was Egyptian or Greek have gone on for a long time now, and will no doubt continue, but it seems safest to say she was ethnically Greek and culturally Egyptian.

Roman Civil War & Cleopatra's Death

During these years, Antony's relationship with Octavian would steadily disintegrate. Octavian was outraged by Antony's behavior and especially the disrespect shown to his sister as well as to himself. He repeatedly rebuked Antony, and, in at least one instance, Antony responded directly. In 33 BCE, Antony returned a letter to Octavian:

What has upset you? Because I go to bed with Cleopatra? But she's my wife and I've been doing so for nine years, not just recently. And anyway, is [your wife] your only pleasure? I expect that you will have managed, by the time you read this, to have hopped into bed with Tertulla, Terentilla, Rufilla, Salvia Titisenia, or the whole lot of them. Does it really matter where, or with what women, you get your excitement?

(Lewis, 133)

Octavian did not appreciate the reply nor any of Antony's other breaches of policy, courtesy, or propriety, and their personal and professional relationship degenerated further to the point where civil war broke out. After a number of engagements, which almost routinely favored Octavian, Cleopatra's and Antony's forces were defeated by Octavian's at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, and, a year later, they both committed suicide. Antony, upon hearing the false report of Cleopatra's death, stabbed himself. He learned, too late, that she still lived, and Octavian allowed him to be brought to the queen, where he died in her arms.

Octavian then demanded an audience with the queen, where the conditions of her defeat were made plain to her. The terms were hardly favorable, and Cleopatra understood she would be brought to Rome as Octavian's captive to adorn his Roman triumph. Recognizing that she would not be able to manipulate Octavian as she had Caesar and Antony, Cleopatra asked for and was granted time to prepare herself.

She then had herself poisoned through the bite of a snake (traditionally an asp, though most scholars today believe it was an Egyptian cobra). Octavian had her son Caesarion murdered, and her children by Antony brought to Rome, where they were raised by Octavia; thus ended the Ptolemaic line of Egyptian rulers.

Conclusion

Although traditionally regarded as a great beauty, the ancient writers uniformly praise her intelligence and charm over her physical attributes. Plutarch writes:

Her own beauty, so we are told, was not of that incomparable type that immediately captivates the beholder. But the charm of her presence was irresistible and there was an attraction in her person and in her conversation that, along with a peculiar force of character in her every word and action, laid all who associated with her under her spell.

(Lives, Antony and Cleopatra, Ch. 8)

Cleopatra has continued to cast that same spell throughout the centuries since her death and remains the most famous queen of ancient Egypt. Movies, books, television shows, and plays have been produced about her life, and she is depicted in works of art in every century up to the present day. Even so, as Schiff notes, she is almost universally remembered as the woman who seduced two powerful men rather than for what she accomplished before meeting them. Schiff writes:

The personal inevitably trumps the political and the erotic trumps all: we will remember that Cleopatra slept with Julius Caesar and Mark Antony long after we have forgotten what she accomplished in doing so, that she sustained a vast, rich, densely populated empire in its troubled twilight, in the name of a proud and cultivated dynasty. She remains on the map for having seduced two of the greatest men of her time, while her crime was to have entered into those same 'wily and suspicious' marital partnerships that every man in power enjoyed.

(299)

Cleopatra was only 39 years old when she died and had ruled for 22 of those years. In an age when women rarely or never asserted political control over men, and female rulers were rare, she managed to maintain Egypt in a state of independence for as long as she held the throne and never forgot what was due to her people. In keeping with the ancient traditions of the land, she tried to maintain the concept of ma'at – balance and harmony – as well as she could under the circumstances of the time, and has come to symbolize ancient Egypt in the popular imagination more than any other Egyptian monarch.

Author's Note: Special thanks to scholars Arienne King and Basil Elkot for contributions to this article.