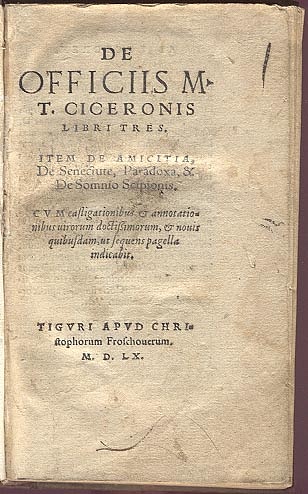

De Officiis is a treatise written by Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 – 43 BCE), Roman statesman and orator, in the form of a letter to his son just after the death of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE. Strongly influenced by stoicism, De Officiis is divided into three books and reflects the author's view on how to live a good life. The first two books are based on the teachings of stoic philosopher Panaetius of Rhodes, with Book I analysing honour and its roots and Book II delving into utility and what is to one's advantage. Book III links honour with usefulness and explores which should prevail.

Marcus Tullius Cicero

Cicero was a Roman statesman and politician, born in 106 BCE, a member of the lower aristocracy called the ordo equester or the equestrians. He studied in Athens and on the island of Rhodes where he probably got his stoic inspiration from. At the minimum age, he became quaestor in 75 BCE, aedile in 69 BCE, praetor in 66 BCE, and finally consul in 63 BCE.

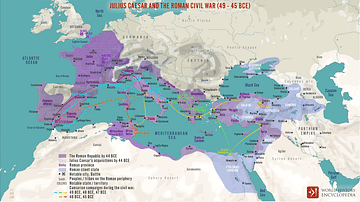

The pinnacle of his political career was probably the Catiline Conspiracy when he was granted emergency powers by the Roman Senate and given the title pater patriae afterwards for saving the Roman Republic. Later on, Cicero, as the proconsul (governor) of Cilicia, was a major participant in Roman politics, supporting Pompey. After the Ides of March, Cicero returned to Rome to defend the Republic from Mark Antony. In 43 BCE Cicero was assassinated by the order of Mark Antony while fleeing Italy.

During his life and political career, Cicero wrote a lot of treatises on a variety of subjects. Being an exquisite public speaker, his most famous texts are written copies of his speeches. Some of these were in defence of a public figure in a court of law, such as Pro Milone (In Defence of Milo), while others were accusing his political rivals. However, he also wrote some important philosophical theses, the most famous being De Re Publica (On the Commonwealth), De Natura Deorum (On the Nature of the Gods), De Legibus (On the Laws), and De Officiis (On Duties).

Book I – Honour

The first book of De Officiis centres around honour and the four major foundations that create it. Cicero approaches the first pillar of honour, the search for the truth, in the most metaphysical sense of human existence. Although rationality has an important part to play in his argument, he examines human action based on curiosity. The search for knowledge is a very unique property of our species, and the author recognises it as one of the main drivers that give meaning to social life, claiming that "the knowledge of truth touches human nature most closely" (Book I. 18. VI.).

However, Cicero argues that this search for the truth must have some utility for the common good and for the Republic. He stipulates that good knowledge is useful knowledge, such as astronomy, dialectics, law, and mathematics. According to Cicero, the knowledge obtained in academic work could only be praised as virtuous, if the theory was to be applied in a public office:

All these professions are occupied with the search after the truth, but to be drawn by study away from active life is contrary to moral duty. (Book I. 19. VI.)

Since humans are naturally social beings, the maintenance of social relations is key for peaceful development and thus constitutes the second pillar of honour. Two major virtues are paramount to achieve happiness in a civilised society; justice and generosity. Cicero presents a very clear definition of justice: “keep one man from doing harm to another (…) and the next is to lead men to use common possessions for the common interests” (Book I. 20. VII.).

Cicero mentions fides or trust as the main propeller of justice. He then criticizes the senators of his time for losing this virtuous trait, especially Julius Caesar, giving the example of the conquest of Massalia, a Greek colony that was an old ally of the Roman Republic. The author goes further and says that the main reason for the ongoing civil war was that values like fear and greed had prevailed over fides.

For justice to prevail, generosity also has to play its part in the equation. Sharing and charity are important for the development of the Republic. However, generosity cannot exceed one's means nor can it harm others as a consequence. The first goal in mind, while being generous, should be the welfare and prosperity of the Republic. The author then criticizes Caesar for not practising virtuous generosity, because he used his money to bribe senators and purchase the trust of the lower classes.

The third pillar of honour, according to Cicero, is fortitude. It is mainly associated with political life and military achievements. However, the aim of military conquest should not be personal glory. Glory should come as a reward for serving one's country. Cicero also asserts that one should achieve apatheia, the total elimination of passions such as desire, fear, pleasure, and sadness. He states that the worst passion is wrath and that one should always have a moderate level of clementia, that is mercy for one's enemies.

The fourth and last bastion of honour is revealed to be decorum. Difficult life choices and dilemmas will emerge, and decorum must play a part by guiding the individual to make a rational and honourable decision. Cicero includes decorum in all of the former pillars as it manifests passively in rational actions: "For there is, in truth, a certain something which is becoming - and it is understood to be contained in every form of virtue" (Book I. 27. IX.).

Book II – Utility

In the second book, Cicero approaches the methods of obtaining and maintaining power. However, he makes it clear that he considers the first book more important.

I believe, Marcus, my son, that I have fully explained in the preceding book how duties are derived from moral rectitude, (…) My next step is to trace out those kinds of duty which have to do with the comforts of life, with the means of acquiring the things that people enjoy, with influence, and with wealth. (Book II, 1, I.)

Book II explores utility, which Cicero defines as everything that can be used as a means to an end. Nonetheless, one should always associate what is useful with what is honourable because everything that is honourable should always be useful and vice versa.

Cicero then emphasises the usefulness of common physical things around us and concludes that the things we humans produce only have value because of human relations. For example, if society did not exist, gold would not have any value whatsoever. The things that have the most use for humanity are people themselves and their actions.

The author argues that a leader should better be loved than feared (later Machiavelli claims the exact opposite in The Prince) but never hated. According to Cicero, when fear exists in the political theatre - the tyrant lives in fear of the people and the people in fear of the tyrant - there can be no stability or progress because social relations are compromised. On the other hand, while generosity is something that promotes social bonds, a political project cannot be based only on that. Generosity uses incentives that will sooner or later run out, and then, as a consequence, social instability will resurface. Therefore, one should appear generous while keeping funds under control.

In order to be successful in politics, one needs to gain people's trust by demonstrating intelligence. People need a leader with common sense, who can decide for the whole community. Cicero argues that the most successful statesmen are those who acquire admiration through fortitude and the path to be a happy and respectable man is to follow a political career with virtue and honour.

Book III – Honour vs. Utility

In the third book, Cicero explains to his son that political life should, most of the times, prevail over other options. This is because political life is the most virtuous if well followed. However, contemplation and leisure are not always bad as long as one returns to public service. The author gives the example of Scipio Africanus who decided to withdraw from his political career not by necessity but by personal choice. Like Scipio, Cicero's son Marcus should consider his studies in Athens not as a time for leisure but as an opportunity to acquire knowledge.

The author then delves into a comparative analysis of expediency and moral rectitude, which is clearly a battle between honour and utility. After presenting many examples of moral dilemmas, the author concludes that the end could never justify the means, as seen in the case of Themistocles:

Themistocles confided to him that the Spartan fleet, which had been hauled up on shore at Gytheum, could be secretly set on fire (…) The result was that the Athenians concluded that what was not morally right was likewise not expedient, and (…) they rejected the whole proposition. (Book III. 49. 317)

After presenting this example to his son, Cicero concludes:

Let it be set down as an established principle, then, that what is morally wrong can never be expedient. (Book III. 50. 319.)

Legacy

Cicero's works left a long-lasting legacy that stills prevails today. His works are not only analysed as a source of philosophical knowledge but are also a time capsule for historians to study the social construction of the late Roman Republic. Later many political philosophers quoted Cicero in their works and studied him as a source for their political theories. Among these philosophers are Saint Augustine, Saint Thomas Aquinas, Machiavelli, Petrarch, Erasmus of Rotterdam, John Locke, and Voltaire. Cicero's views on patriotism, moral values and virtues and political strategy are still reflected in modern western philosophy and such concepts as modern citizenship.