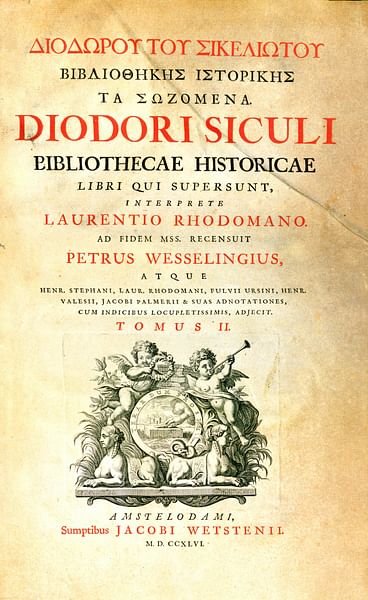

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (active 1st century BCE) was a Greek historian, known for his universal history Bibliotheca Historica. Originally, it was a 40-volume monumental work, covering the history of the Mediterranean region from mythical times to his own lifetime, around 60/59 BCE. Today 15 books survive complete and others in fragments. He has been accused of being a mere compiler of earlier sources, however, Diodorus' use of these writings also preserved works that may have been lost without him, and in the modern day the Bibliotheca is recognized for its unity of themes.

Early Life

Little is known of his early life - even his birth and death dates are speculative. It is known that he was from Agyrium, Sicily, and was alive during the time of Julius Caesar (l. 100-44 BCE) and Octavian, the future Augustus (l. 63 BCE - 14 CE). It is believed by many historians that he died during the time of the Second Triumvirate of Octavian, Lepidus, and Mark Antony around 36 BCE. According to an inscription on a tomb in Agyrium (believed to be his), he was Diodorus son of Apollonius. Although his hometown was considered impoverished by the Roman orator and statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BCE), others suggest he may have been wealthy because he made no reference in his writings to having been in public office, thereby enabling him to spend almost 30 years writing, traveling and researching.

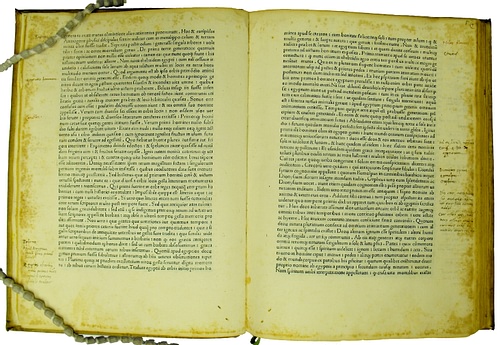

Bibliotheca Historica

His only known work, the 40 books of the Bibliotheca Historica or Historical Library, covered the history of the entire Mediterranean region from mythical times to around 60/59 BCE. Unfortunately, only 15 (Books 1-5 and 11-20) of the original 40 books have survived; the rest are in fragments. Aside from his own research through travel, he made use of earlier histories. He also lived in Rome for several years and had access to excellent sources there. While he was wrongly accused by some early historians of only being a compiler, his history is considered by modern historians to be the most extensively preserved history of antiquity by a Greek historian. It is thought he started writing in the early 50s BCE and began publishing in the 40s BCE, thus preceding the Roman historian Titus Livius, better known as Livy (c. 64 BCE - c. 12 CE).

Initially intending to extend his history to 40 BCE, he stopped two decades earlier, realizing that contemporary history in such a turbulent period was difficult and possibly even hazardous. At the end of his history, he made reference to the rise of Julius Caesar and his triumph in the Gallic Wars, most notably the invasion of Britain and the bridging of the Rhine River. Moreover, having witnessed the collapse of the First Triumvirate of Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus, Diodorus probably realized it was a politically dangerous period in which to write and chose to stop. Although he may or may not have known any public officials personally, it is thought that he was an admirer of Caesar.

In the introduction to his history, he provided the reader with an outline of his work. It is interesting to note his use of “our” and “we” in the paragraph:

Since my undertaking is now completed, although the volumes are yet unpublished, I wish to present a brief preliminary of the work as a whole. Our first six books embrace the events and legends previous to the Trojan War, the first three setting forth the antiquities of the barbarians, and the next three almost exclusively those of the Greeks; in the following eleven we have written a universal history of events from the Trojan War to the death of Alexander. (21)

Contents

Although he claimed to cover all of history, he concentrated his initial volumes on Greece and his homeland of Sicily until his sources on Rome improved. From the outbreak of the First Punic War (264-241 BCE) with Carthage, he gave greater attention to the city and the Roman Republic. His work on his homeland has been credited as being an essential source for classical Sicily especially its coverage of the Sicilian slave rebellion of the 2nd century BCE. He claims to have traveled extensively, visiting Egypt sometime between 60-57 BCE; however, his critics place doubt on his claims regarding other regions and maintain he does not seem acquainted with such Greek and Asian cities as Athens, Miletus, Ephesus, and Antioch.

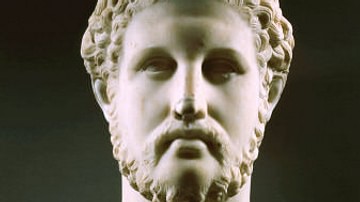

As he mentions in his book one outline, Books 1-6 cover the mythical history of the non-Hellenic and Hellenic people, the area's geography and ethnography ending with the downfall of Troy. Books 7-17 include Greek history from the Trojan War through Philip II of Macedon until the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, while Books 18-40 continue until Caesar's Gallic Wars. The surviving Books 11-20 embrace the years 480-302 BCE. It is suggested by some historians that he may have considered writing two more books covering history through 46/45 BCE, but that is pure conjecture.

While he was proud of his own undertaking, it is apparent that he truly appreciated those historians who preceded him. In the opening of the first book, he gave thanks to the historians who paved the way for him:

It is fitting that all men should ever accord great gratitude to those writers who have composed universal histories, since they have aspired to help by their individual labours human society as a while; for by offering a schooling, which entails no danger, in what is advantageous they prove their readers through such a presentation of events, with a most excellent kind of experience. (5)

Never denying his use of earlier historians' material, he used the works of Hecataeus of Miletus (c. 550 - c. 476 BCE) for information on Egypt, the Greek historian Timaeus (c. 350 - c. 260 BCE) for material on Sicily and the Olympiads, and the Greek historian/diplomat Megasthenes (350-290 BCE) for first-hand accounts of India. Aside from those mentioned above, he was influenced by the Greek historian and author of The Histories Polybius (c. 208-125 BCE), who wrote on the Roman Republic, the statesman Hieronymus of Cardia, who was Alexander's contemporary and wrote on the Wars of the Diadochi, the historian Ephorus of Cyme (c. 405 - c. 330 BCE), whose 30-book history is lost, and the Stoic philosopher/historian/astronomer Posidonius (c. 135-51 BCE). Thankfully, because of his history, the writings of these historians and others have not been lost.

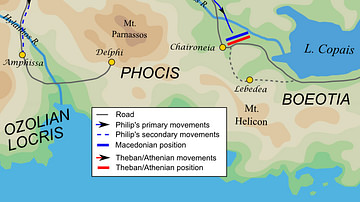

Although faulted by some for being a simple compiler, he did not always agree with the interpretations of those historians who preceded him, even the fathers of history Herodotus (c. 484 - 425/413 BCE) and Thucydides (c. 460/455 - 399/398 BCE). Paul Cartledge in his book Thebes writes of Diodorus' divergence from a historical episode written by the noted Greek historian Xenophon (c. 430 - c. 354). Xenophon was anti-Thebes and pro-Sparta and failed more than once to recognize a Theban victory over Sparta. One such incident was a Theban victory at the Battle of Leuctra in Boeotia in 371 BCE. Although Diodorus recognized Xenophon's oversight and “did full justice by way of compensation” for the omission and corrected the error, Cartledge still claimed the historian's passage was “selective, inaccurate and dull.” (11)

Diodorus wisely chose to end his history before the rise of Caesar and Augustus. It was a restless time for Diodorus for he was probably in Rome at the time of Caesar's assassination in 44 BCE and the revenge of Octavian (Augustus) against the assassins. Having settled in Rome around 56 BCE, he saw a Rome that was in transition. Rome was conquering the Mediterranean Sea, and people like Cicero were writing unfavorably about it. Unfortunately for Cicero, his outspoken criticism brought about his death. And, not unlike Cicero, Diodorus did not like what he saw. His writings reveal his disgust with Rome and what it was becoming: a ruthless conqueror. He saw the cruelty in the treatment of the poor and enslaved and the impiety of Rome and its people.

In his book The Rise of Rome, historian Anthony Everitt quotes Diodorus concerning the plight of the slaves working in the mines where many preferred death to simple survival: "Day and night they wear out their bodies digging underground, dying in large numbers because of the terrible conditions they have to endure" (Everitt 330). And, quoting Diodorus, Everitt wrote that the Romans treated those they conquered as "benefactors and friends … but once they controlled virtually the entire inhabited world, they confirmed their power by terrorism and by the destruction of the most illustrious cities" (345). Everitt contrasts this new Rome with that of a time long past stating that this new brutality of the Romans was accompanied by corruption in public life.

Diodorus also criticized the treatment of the city's poor who had been forced off their land, fleeing into the city searching for work. According to historian Mike Duncan's The Storm before the Storm, a few became rich while the poor grew weaker due to the "oppressive weight of poverty, taxes and military service" (20). Referring to the work in the mines, he added that "the work was fatal, but the profits astronomical" (51). This changing Rome may have been influential in Diodorus' decision to end his history when he did.

Legacy

Although crediting Diodorus for writing in a clear and unaffected style, some historians, reviewing Diodorus' history, often criticized him, citing his lack of military and political experience. This may have affected his judgment and contributed to poor historical reliability. More modern historians see him differently, and while they understand and recognize that there remain some errors and distortions, Diodorus has been commended, not criticized, for his unity of themes and creativity. However, whether one commends or criticizes, his history must be appreciated, if nothing more, than for its use of earlier histories which could have been lost and long forgotten.