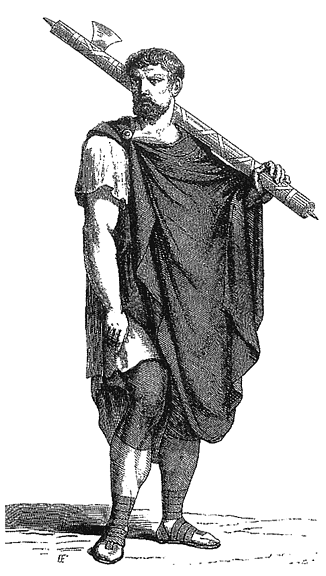

The fasces were a bundle of rods and a single axe which were carried as a symbol of magisterial and priestly authority in ancient Rome. They featured prominently in important administrative ceremonies and public processions such as triumphs. The symbol was adopted by later cultures to represent order and strength through unity, notably the fascist movement in Italy in the 20th century CE. The fasces are still visible today in many official contexts as a symbol of Republican principles, for example, in the United States' House of Representatives and on the cover of passports of French nationals.

Evolution & Form

The symbol of the fasces was probably borrowed by the Romans from the Etruscan kings, as evidenced by the excavation of a miniature iron version from a 7th-century BCE Etruscan tomb at Vetulonia. The Roman fasces were composed of a bundle of rods (vergae) which were made from either birch or elm wood. Rounded or rectangular in form the rods were typically 1.5 metres (5 ft.) in length. The rods were bound together with a single-headed axe and a slightly longer central staff using red leather straps. The axe was not only ceremonial but was used in the early Republic to execute those sentenced to death. For this reason, when the axe was removed from the bundle it was to signify that a citizen could launch an appeal (provocatio) against a death penalty decision.

Fasces & Magistrates

Fasces were typically carried over the left shoulder of magisterial attendants known as lictors (lictores) as symbols of judicial authority. During official duty magistrates would be preceded by the lictors and the fasces which indicated to the public that a magistrate was coming and remind them of his authority to arrest or summon any person he saw fit. If one magistrate met another, the lictors of the less senior would lower their fasces in recognition of the greater standing of the other magistrate. When a magistrate died, he had the right to have a fasces representation on his tomb. Conversely, if a magistrate committed any wrong-doing, not only was he obliged to resign but his fasces were ceremoniously broken to symbolise his disgrace and loss of authority.

Widening the Function of Fasces

During the Republic consuls (chief magistrate), and later proconsuls, also had their personal lictors bearing the fasces. Then only when the consul was outside Rome did the fasces have the axe element as this came to signify military authority. During the triumph of a Roman military commander the fasces were carried by lictors in the procession and decorated with laurel leaves. The emperor also decorated his fasces in the same way. At the other end of the scale, municipal magistrates may have had, according to Cicero, a lesser version, the bacilli, which had only two rods and no axe.

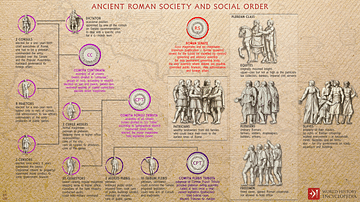

Over time the use of lictors and fasces further widened to represent the authority of other officials and religious posts such as praetors (one step down from consuls), propraetors, the wife of the emperor in her role as imperial cult priestess, and the Vestal Virgins. A ranking system developed where the more senior positons had the right to bear a greater number of fasces. In the Republic magistri equitum (cavalry commanders) and praetors had six, proconsuls and consuls had 12, and dictators had 24. In the Principate, senatorial governors had a number indicating their experience, imperial legates (senators who were also military commanders) had five, and emperors had 12, with Augustus perhaps having 24 fasces whenever he was outside Rome.