The Flight to Varennes was a pivotal moment of the French Revolution (1789-1799), in which King Louis XVI of France (r.1774-92), his wife Queen Marie Antoinette (1755-93), and their children attempted to escape from Paris on the night of 20-21 June 1791. They made it to the small town of Varennes-en-Argonne, where they were arrested and returned to Paris.

Despite efforts by the National Constituent Assembly to save face by making it appear that the king was kidnapped rather than escaped on his own volition, the flight proved that Louis XVI could no longer be trusted, and drastically increased the public's hatred and distrust of the monarchy. For the first time, the idea of republicanism was no longer a topic on the fringe of revolutionary conversation and calls for the establishment of a French republic mounted. The Flight to Varennes marked the second major schism within the Revolution, following the alienation of the Catholic Church the previous year, as the Jacobin Club became split between republicans and constitutional monarchists.

Varennes was a traumatic moment for France; feelings of betrayal and anxiety were prevalent. The apparent involvement of foreign powers in the plot would lead to fears of invasion, fears which would help start the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802) less than a year later. As for the king and queen, their flight would mark them as traitors in the eyes of the people, contributing to their executions in 1793.

Royal Prisoners

Since 6 October 1789, Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, and their children had been living in the Tuileries Palace in Paris, under the watchful eye of the bourgeois militia known as the National Guard and its commander Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834). The king and queen had been removed from the luxurious palace of Versailles at the forceful insistence of the National Guard and 7,000 of Paris’ market women; the Women’s March on Versailles, as it became known, effectively stripped the royal couple of much of their remaining autonomy. Louis and his family were now virtual prisoners of the Revolution.

Yet, in the early months of 1790, the royal family’s position was not so bleak. Although forced to consent to various policies he personally disagreed with, Louis XVI was seen by many to have been reconciled with the Revolution, and had even been hailed as “Restorer of French Liberty.” Constitutional monarchists such as Honore-Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau (1749-1791) supported the king within the Assembly and worked to ensure that the forthcoming constitution would not deprive the monarch of too much authority. According to his own journal, in early 1790 the king was still allowed to enjoy his daily rides, and still carried out royal ceremonies and met with foreign dignitaries in the court of the Tuileries.

Escape, therefore, did not lay heavy on Louis’ mind during these early days of confinement. Marie Antoinette, however, did not share her husband’s lack of concern. Traumatized by the events of 6 October, the queen did not forget how members of the mob had tried to kill her and her children. “Kings who become prisoners are not far from death,” she reportedly told her lady-in-waiting. She became visibly upset when meeting an English lord who wore a ring containing a lock of regicide Oliver Cromwell’s hair (Fraser, 305). Clearly, she expected the worst. Still, when it was suggested that she leave France by herself for the Austrian court at Vienna, she refused, unwilling to leave her husband.

Outside of the Tuileries, plots were made to free the royal family almost immediately after their confinement. In December 1789, the marquis de Favras planned to kidnap the king and take him to the safety of the fortress at Metz. However, Favras roused the suspicions of Lafayette, who had him watched. The plot was uncovered and Favras was hanged in February 1790. Yet that was not the last of the attempts to remove Louis from Paris. Even Mirabeau, the king’s secret advisor, warned him that it was in the monarchy’s best interests to leave Paris and set up court in a less revolutionary city such as Rouen. Louis stubbornly refused.

Things began to unravel in July 1790, when the Assembly passed the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which subjected the French Catholic Church to the government’s authority, forcing clerics to swear oaths of loyalty to the constitution. This policy caused a major rift between Revolution and the Church. A deeply pious king, Louis XVI had nonetheless accepted the Civil Constitution. But after large numbers of French clerics refused to take the oath, and after learning of the pope’s private condemnation of it, the king began to have second thoughts.

In February 1791, the king's two aunts announced their intention to go to Rome and speak with the pope. Louis himself supervised the arrangements for their journey. Yet on the day of their departure, angry crowds of women, spurred on by the Jacobins and the radical Cordeliers Club, protested in front of royal residences, suspecting a plan of emigration by the royal family. The royal aunts eventually made it to Rome, but the debate over his relatives' freedom of movement disturbed the king.

The point was driven home during Easter week, 1791. It had become common knowledge that, the Sunday prior, Louis XVI had taken communion from a refractory priest who had refused to swear loyalty to the constitution. As the royal family attempted to set out for the palace of Saint-Cloud, where they wished to spend their Easter, a huge crowd surrounded their carriage and stopped it from moving. For more than an hour, the royal couple sat trapped in their carriage, as the crowd hurled verbal abuse toward them. As the queen sat weeping with frustration, the king made a futile attempt to address the crowd, asking why “he who gave the French nation its freedom should now be denied his own” (Schama, 549). Not even Lafayette’s arrival could calm the masses; the general’s own troops refused his command to disperse the crowd. Humiliated, the royal couple had no choice but to return to the Tuileries. If Louis XVI had not believed himself to be a prisoner before, he certainly did now. And with the sudden death of Mirabeau in early April, he was now left with few allies in the Assembly, which was increasingly dominated by the hostile Jacobins. Something drastic had to be done.

The Plan

A promise of salvation came from an old friend. Count Axel von Fersen (1755-1810) was a Swedish nobleman and adventurer who had served in the French army during the American Revolutionary War. He was also a close intimate of Marie Antoinette and, quite possibly, her former lover. Now, Fersen took it upon himself to help the royal family escape the dangers of the Revolution.

The pieces were already in place. From the frontier, the Marquis de Bouillé, commander of the garrison at Metz, indicated that he could gather enough soldiers to ensure the royal family’s protection. A cousin of Lafayette, Bouillé had proven his royalist devotion the previous year when he had crushed a military revolt at Nancy with particular brutality: 20 soldiers had been hanged at his command, and one was even broken on the wheel. The plan was for the king and queen to escape Paris and link up with Bouillé’s men, who would escort them to the border with the Austrian Netherlands. There, four Austrian regiments would be waiting to take them to safety, guaranteed by the Austrian emperor and Marie Antoinette’s brother, Leopold II (r. 1790-92). From there, the royal family would have the option of instigating a counter-revolution.

It was decided that the king and queen would rendezvous with Bouillé at Montmédy, a garrison town bordering the Austrian Netherlands. The closest border from Paris, it would be about a two days’ drive, if the horses were driven hard. Perhaps comforted by the involvement and coordination of Fersen, Louis and Marie Antoinette agreed to the plan. They were to assume fake identities: the queen was to act as a governess, the dauphin was to pose as a girl named Aglae, and Louis himself was to go by the alias "M. Durand". All was set, and the plan went ahead on the night of 20 June 1791. Of course, everything would soon fall apart.

The Escape

At 8:30 pm, 6-year-old Louis-Charles, dauphin of France, went up to his apartments for supper. Two and a half hours later, his parents retired to bed. Once the royal family was safely assumed to be asleep, servants in on the plot quickly dressed the dauphin and his sister, princess Marie-Thérèse, before escorting the children to the berlin carriage that awaited them. Joined by their aunt, Madame Elizabeth, the three escapees awaited the king and queen. Disguised in a round hat, wig and plain coat, Louis XVI soon slipped past his guards and joined them with little fuss. There was one close call: Marie Antoinette had to hide from Lafayette, who was making his nightly rounds of palace security. Shaken by this near discovery, the queen then became lost in the dark. It was half an hour before she made her way to the carriage.

Carrying its five royal passengers, the berlin exited Paris at around 2 am that night, cloaked in the darkness of a moonless sky. Outside Paris, Fersen met them with another carriage attached to faster horses. As the royal family transferred their belongings into the second carriage, Fersen promised to meet them in Brussels before disappearing into the night. Now in the faster carriage, the royals’ flight continued.

Around the break of dawn, the carriage’s wheel hit a stone post on a bridge, breaking the traces. It would take a half hour to get going again, meaning the carriage was now badly behind schedule. This lateness spooked the Duke of Choiseul, a young nobleman who had been instructed to meet the king at Pont de Somme-Vesle with a detachment of soldiers and bring them the rest of the way to Montmédy. Harassed by villagers who thought the soldiers were there to collect taxes, Choiseul panicked and, fearing the plan had been abandoned, fled into the woods with his troops.

By this point, the disappearance of the royal family had been discovered in Paris and the alarm had been raised. News of their escape travelled faster than the carriage itself. So, when the royals arrived at the town of Sainte-Menehould, lacking protection from Choiseul's soldiers, vigilant citizens were already keeping their eyes out for them. One such citizen, a postmaster named Drouet, recognized the royals as they passed through Sainte-Menehould on the afternoon of 21 June; he would later claim he recognized the king from his portrait on a 50-livre assignat.

Drouet sprung to action. As an ex-dragoon, he was able to ride fast and beat the royal carriage to the small town of Varennes-en-Argonne, where he raised the alarm. When the carriage arrived, it was stopped by the town’s procureur, who ordered the family out and detained them in the upstairs room of a candlemaker’s house. Meanwhile, the townspeople of Varennes alerted the National Assembly. The next morning, the royal family was confronted by couriers from the Assembly, who, backed up by contingents of the National Guard, demanded their immediate return to Paris. Angrily, Marie Antoinette denounced the insolence of the Assembly to make such a demand while Louis lamented his loss of power, crying, “there is no longer a king in France!” (Schama, 556). After less than twenty-four hours of freedom, the king was again a captive.

Return

Around 6,000 National Guardsmen and armed townspeople surrounded the carriage on its return journey to Paris, enough to deter Bouillé from making a rescue attempt; upon hearing of the plot’s failure, Bouillé fled into Belgium. Of the other conspirators, Choiseul was captured and imprisoned, and Fersen escaped to Koblenz, where he joined with Louis XVI’s exiled brothers, the counts of Artois and Provence, who were building a counter-revolutionary court of French emigres (Provence had fled Paris a few hours after the king but had evaded capture himself). Meanwhile, the captured royal carriage was joined by Lafayette, as well as three representatives of the Assembly; two of them, Jérôme Pétion and Antoine Barnave, sandwiched themselves in between the king and queen in the already crowded carriage. The seven rode together in the cramped space for more than two days.

Pétion was an offensive presence. He pulled on the dauphin’s hair and forced the child to repeatedly read aloud the revolutionary mottos inscribed on his buttons. Deluded by his own vanity, Pétion convinced himself that the king’s sister, Madame Elizabeth, was flirting with him, later recalling her “smiles on a summer’s night” (Fraser, 344). In contrast, Barnave, the 29-year-old deputy who had built a reputation as one of the Assembly’s “triumvirs”, was quite the gentleman. He engaged in pleasant conversation with Madame Elizabeth and the queen, who quickly won him over with her charm. Marie Antoinette’s sad demeanor and refined manners moved Barnave to sympathy; thereafter, he would keep a correspondence with her that would ultimately result in his own political undoing and execution.

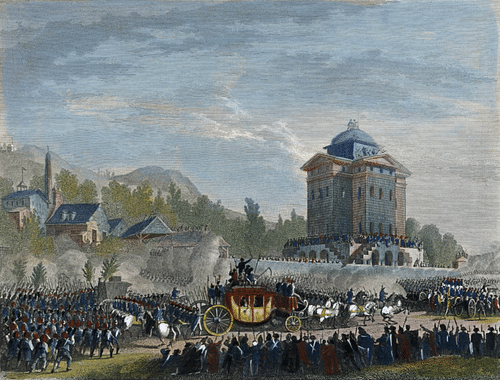

Travelling at walking pace, the carriage would take three days to reach Paris. It finally arrived on 25 June, where it was met by a large crowd that had been instructed to remain silent, to neither cheer nor insult the royal family; signs hung up across the city on Lafayette’s orders threatened that, “whoever applauds the king shall be flogged; whoever insults him shall be hanged” (Fraser, 345). At 8pm, the family finally arrived outside the Tuileries’ gates, weary from the past few days of travel. Despite the excitement of the whole ordeal, Louis XVI’s entry in his journal was characteristically succinct: “Five nights spent outside Paris” (Fraser, 348).

Reaction

The flight of the king caused an existential crisis within the National Assembly. For two years it had been laboring to craft a constitution based around the principle of constitutional monarchy. Now, on the verge of that constitution’s completion, the single night of the king’s escape had thrown everything into jeopardy. By his actions, the king had both nullified his previous support of the Revolution and had drained all hope for future cooperation. The hard work of two revolutionary years was in danger of becoming undone.

Desperate to save face, the Assembly concocted a story that the king had not fled on his own accord, but had instead been kidnapped by the devious Marquis de Bouillé, and was rescued by heroic citizens. Bouillé, safely across the border, confirmed this, hoping the lie would help the king. Yet this story, already tenuous at best, completely fell apart after the discovery of the king’s note.

On the night of the escape, Louis XVI had left behind a manifesto, in which he renounced the Revolution at great length, while disavowing his own forced participation in it. He expressed his frustration at his imprisonment in Paris, his anger at the violation of property and the “complete anarchy in all parts of the empire” (Doyle, 152). He had denounced the Revolution’s treatment of clergy, denounced the rise of the Jacobins and, worst of all, had denounced the constitution.

The evidence was damning. Louis XVI would never be a dutiful citizen-king. As word of this betrayal spread throughout the nation, panic began to sprout regarding the king’s intentions. Would he have invaded the country at the head of an Austrian army, had he gotten away? Would the foreign powers invade anyway? Any doubt surrounding these questions was dispelled when, on 27 August, the monarchs of Austria and Prussia released the Declaration of Pillnitz, in which they voiced their support for Louis XVI against the Revolution. Europe was already sliding towards war.

In the Assembly, meanwhile, the flight caused the second great divide of the Revolution thus far, as deputies debated how to handle the king’s act of treason. The result was a split in the Jacobin Club itself. Some members, led by Barnave, Lafayette, and Alexandre Lameth formed the Feuillant Club to rival the Jacobins, with the goal of pressing on with their vision of constitutional monarchy; following his captivation with the queen, Barnave even labored to revise the constitution to be more favorable to royal authority. The remaining Jacobins, led by Maximilien Robespierre, Georges Danton, and Jacques-Pierre Brissot, and under the influence of the famous radical Englishman Thomas Paine, drifted closer to republicanism, something that had never been seriously considered before the king’s flight.

Tensions flared between the two groups until July 1791, when a petition was drawn up by Brissot, demanding the king’s removal. On 17 July, over 50,000 French citizens gathered on the Champ de Mars to sign it. They were met by Lafayette and his National Guard, who had been sent to disperse them. Greeted first by jeers, then by a volley of stones, the National Guardsmen opened fire into the unarmed crowd, killing 50 people. In the following days, Lafayette clamped down on the anti-monarchical leaders, forcing many to go into hiding. The Champ de Mars Massacre marked a point of no return in the spiraling disunity of the Revolution.

Eventually, the Assembly decided to suspend the king’s powers until he consented to the constitution. But it was clear that there would be no more reconciliations between king and Revolution. For his part, Louis XVI embarked on a quiet crusade of counter-revolution, as best he could from his confinement in the Tuileries. However, his credibility as a citizen-king was ruined. Hatred and distrust would only mount over the coming year; now, it was not just the institution of the monarchy that was hated, but the king and queen themselves. A little over a year after Varennes, the monarchy would be abolished in favor of a republic. Shortly thereafter, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were executed for their treason.