Franz Liszt (1811-1886) was a Hungarian composer of Romantic Music. Liszt first gained international fame as a piano virtuoso, an activity in which he was a pioneer, and then as a composer of piano works and symphonic poems, a form he created. A prolific transcriber of those who went before and a generous supporter of other composers, Liszt made a lasting contribution to the evolution of music.

Early Life

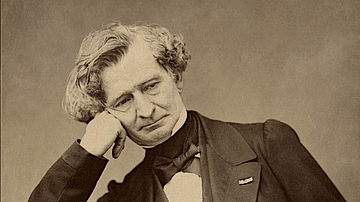

Franz Liszt was born in Raiding on 22 October 1811. The region was then part of Hungary but today it is part of eastern Austria. Franz's father, Adam Liszt, was an official at the court of Nikolaus II, Prince Esterházy (1765-1833), and an amateur musician who taught Franz the piano. Prince Nikolaus had employed the composer Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) to work at his court, and when Franz showed his obvious talent as a pianist he funded the boy's further musical education in Vienna in 1822, a cause encouraged by financial help from several other nobles. In Vienna, Franz studied under Carl Czerny (1791-1857) and Antonio Salieri (1750-1825). Beethoven met the young Hungarian and was impressed with his skills. The Liszt family moved to Paris in 1823. They visited London three times, with Franz playing before George IV of Great Britain (1762-1830). Settling in Paris from 1827, Liszt met the composer Hector Berlioz (1803-1869), whose Romantic ideals would deeply influence the Hungarian. He continued his education under such noted teacher-composers as Ferdinando Paer (1771-1839) and Anton Reicha (1770-1836).

Virtuoso Piano Player

Liszt's destiny was shaped when he heard the great violin virtuoso Niccolò Paganini (1782-1840) play in Paris in 1831. The charismatic performance of the violinist inspired Liszt to try and emulate that success with the piano. As a composer, Liszt was later inspired by Paganini's Caprices to write his Transcendental Studies and Grandes études de Paganini (both 1851).

Liszt, after long hours of practice every day for several years, did indeed become a virtuoso player. He was helped by his long muscular fingers and thumbs, and his style of playing was certainly distinctive. Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) once remarked: "I have not seen any musician in whom musical feeling ran, as in Liszt, into the very tips of the fingers and there streamed out immediately" (Wade-Matthews, 366). As the music historian C. Schonberg notes:

He had everything in his favor – good looks, magnetism, power, a colossal technique, an unprecedented sonority, and the kind of opportunism (at least in his early years) that could cater to the public in the most cynical manner.

(212)

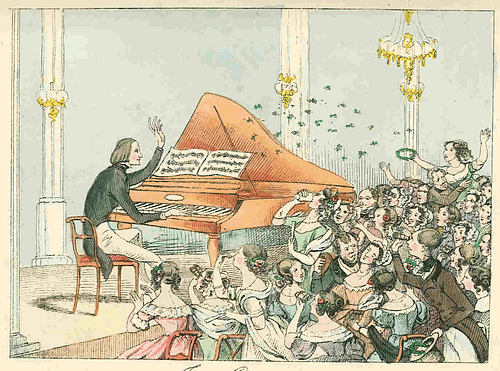

Liszt became such a popular attraction in the salons of the well-to-do, especially with the female audience members, that his idolisation became known as 'Lisztomania', a term coined by the poet Heinrich Heine (1797-1856). Ladies gasped and swooned before this devil of the keyboard, they even scuffled to have possession of the maestro's gloves if he was careless enough to leave them at his piano or if he had tossed them dramatically to the floor as he often did before he began to play. Liszt fuelled the mania by playing as often as possible and selecting the showiest pieces to play, usually his own music. In addition:

He did much to raise the social status of performing musicians. His concerts were also highly innovative: he invented the term 'recital' and was the first performer to appear regularly without supporting artists; he was the first to turn the piano sideways, rather than sit facing the audience; and he was the first to play the range of repertory.

(Sadie, 226)

By 1840, Liszt had established himself as the greatest-ever piano performer. He toured and gave breathtaking recitals, often to raise funds for charitable causes, across Europe from Ireland to Russia at all manner of locations, from palaces to village halls. There was even a performance in Constantinople (now Istanbul). Then, in 1847, Liszt gave up touring to focus on composing, his future public performances being rare and largely limited to charity events where he did not accept a performance fee.

Character & Relationships

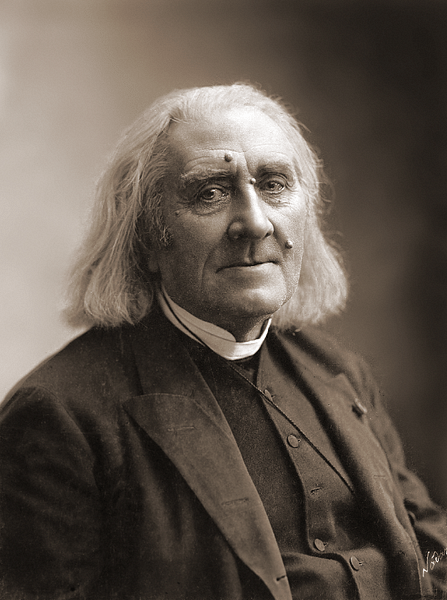

Liszt was tall, thin, and he wore his hair long. Schonberg gives the following summary of Liszt's complex character:

He could be kind and generous, yet could turn around and be arrogant and capricious. He was vain and needed constant adulation, yet he could be genuinely humble in the presence of a genius such as Wagner…To many he was the Renaissance Man of music. His admirers could see only his good points. To others he was all tinsel and claptrap…

(213)

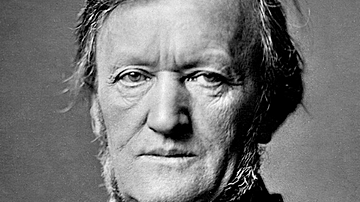

For a man known for his piety in his old age, Liszt certainly enjoyed some amorous adventures in his youth. The pianist began a relationship with Countess Marie d'Agoult in 1834. After the married Marie became pregnant with Liszt's child, the couple lived for a time in Switzerland and then Italy. The travels of this period inspired the composer to write a number of piano pieces grouped into three 'years' and collectively titled Années de pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage). Ultimately, the couple had three children together: Daniel died of consumption aged 20 in 1859, Blondine died in 1862, and the third, Cosima (b. 1837) went on to marry the conductor Hans von Bülow (1830-1894) and then the composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883). The latter arrangement put a strain on Wagner and Liszt's relationship, but the two were eventually reconciled. Liszt and the Countess lived apart from 1839 and fully separated in 1844, their relationship unable to stand the stress of Liszt's constant touring.

In 1848, Liszt took up his position as the music director of the Weimar ducal court – he was given the flamboyant title of 'Kapellmeister Extraordinary'. He now lived with Princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein, who was estranged from her husband and trying to secure a divorce (something she never managed). It was at Weimar that Liszt now wrote many of his most influential pieces.

Weimar

Liszt wrote two symphonies inspired by the Faust legend, a figure who strikes a deal with the Devil to gain great knowledge and power at the cost of his soul. Liszt composed the two-movement Dante Symphony (full title: A Symphony to Dante's Divine Comedy) c. 1856 and the Faust Symphony c. 1857. The latter has three movements: Faust, Gretchen, and Mephistopheles.

Liszt created the symphonic poem (and coined the term itself), essentially a one-movement symphony but inspired by a literary text, artwork or even a landscape. At Weimar, Liszt composed a whole series of symphonic poems such as Tasso, Les préludes based on a poem by Alphonse de Lamartine, Mazeppa, Hamlet, and Hunnenschlacht (Battle of the Huns). He composed the Piano Concerto in E flat (1853) – which gives unusual prominence to the humble triangle, the Totentanz (Dance of Death) for piano and orchestra (1849 but revised twice), the Hungarian Rhapsodies, and the Harmonies poétiques et religieuses cycle of piano pieces.

Never entirely satisfied with his work, the composer frequently revisited pieces to revise them over his long career. In addition, it is noteworthy that some of Liszt's piano works are a real challenge to play, even for an accomplished pianist. Other works, in contrast, seem irresistible to almost all piano players, notably songs like Liebestraum No. 3 (Dream of Love). His Piano Sonata in B minor (1854), with its twisting manipulation of a central theme, is considered a key piece of the Romantic music movement.

Liszt supported other composers throughout his career, transcribed hundreds of works by others, and he formed a centre in Weimar for up-and-coming composers who were pushing against the rules of classical music or pioneering music in their own countries such as Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) in Norway and Bedrich Smetana (1824-1884) in Bohemia. As a conductor, Liszt showcased works by Richard Wagner, Hector Berlioz, Franz Schubert (1797-1828), Robert Schumann (1810-1856), Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901), and Gaetano Donizetti (1797-1848) amongst many others. Liszt particularly championed works of opera, perhaps as some sort of compensation for his own single foray into that field, his Don Sanche of 1825.

Liszt's time at Weimar came to an end after the conservative society there had finally had enough of his scandalous relationship with Princess Carolyne who could not persuade her husband to give her a divorce despite appealing to the Pope for help. Liszt's promotion of up-and-coming composers and their new ideas did not endear him to the people of Weimar either. Liszt brought his Weimar period to an end when he moved to Rome in 1861.

The Abbot in Rome

As an older man, Liszt described himself as the Abbé Liszt (Liszt the Abbot) and wore a cassock. In Rome and single again, he took the decision to join the priesthood in 1865, albeit taking only minor orders (doorkeeper, reader, acolyte, and exorcist). Liszt never gave up women, although his orders did not, in any case, include celibacy. Schonberg is of the opinion that the composer "never took his religion very seriously. He only made a great show of taking it seriously" (214). There were those who described the composer as 'Mephistopheles in a cassock', a not unjustified title given such scandals as that involving one of many lovers, Olga Janina, who tried to shoot Liszt and then take her own life.

Liszt continued to compose but now focused on sacred music. He had already turned in this direction three years before with his oratorio Die Legende von der heilige Elisabeth (Legend of St. Elizabeth). By 1867, he had completed his Christus oratorio. Other sacred works included songs, Masses, and organ and piano works. Oddly, though, Liszt remained attracted to the Faust legend, producing three more of his Mephisto Waltzes in 1880, 1883, and 1885.

Liszt's Most Famous Works

The most famous works by the composer Franz Liszt include:

Années de pèlerinage - Years of Pilgrimage anthology of piano pieces (1836-77)

19 Hungarian Rhapsodies for solo piano (1846-85)

Les préludes symphonic poem (1848, revised 1854)

Piano concerto No. 1 (1849)

Piano concerto No. 2 (1849)

Funérailles for solo piano (1849)

Tasso symphonic poem (1849)

Liebesträum piano works (1850)

Mazeppa symphonic poem (1851, revised 1854)

Orpheus symphonic poem (1853-4)

Piano Sonata in B minor (1854)

Dante Symphony (1854-56)

Faust Symphony (1857)

E-flat Piano Concerto (1857)

4 Mephisto Waltzes (1861-85)

Die Legende von der heilige Elisabeth – Legend of St. Elizabeth oratorio (1862)

Christus oratorio (1867)

Death & Legacy

Liszt regularly visited Hungary from 1869, often staying several months at a time, typically in the spring and autumn. He spent his summers in and around Weimar and the winters in Rome. In Pest, the composer set up a music academy, and in 1875, he was appointed the director of the Hungarian Royal Academy. He continued to teach and gave master classes, which were attended by just about every up-and-coming pianist of note in Europe.

In 1882, Liszt was inspired by a premonition of the death of his son-in-law Wagner to write his La lugubre gondola piano piece. Wagner, as it happened, died the next year of a heart attack while in Venice. In 1885, Liszt added to his collection of solo piano works titled Hungarian Rhapsodies to make a total of 20 (but only 19 were published). Most critics see little about them which is Hungarian and would prefer a more suitable title like 'Gypsy'.

Liszt's final compositions were more experimental: "the sparseness of texture, harmonic ambiguity and dark expressive remoteness look forward daringly to the twentieth century" (Sadie, 227). The last of the founding generation of Romantics, Liszt had perhaps glimpsed the future of music and the Modernists yet to come. In 1886, he toured England and performed in front of Queen Victoria (r. 1837-1901), who gave him a bust as a memento. Physically frail in his final years, Franz Liszt died of pneumonia in Bayreuth in Bavaria on 31 July 1886. He was buried in the city's cemetery.

Liszt was a pioneer in his creation of the symphonic poem and his ideas on the virtuoso piano player, but he was influential in several other ways, too, as here summarised by the musicologist D. Watson:

In his late works he anticipates the whole-tone and pianistic-impressionistic techniques of Debussy, the atonality of Schoenberg, the sparse linear textures of Webern and the Hungarian works of Bartók…His later admirers were as diverse as Busoni, who may be regarded as his spiritual heir, and Stravinsky, who praised Liszt the pioneer.

(Arnold, 1073)