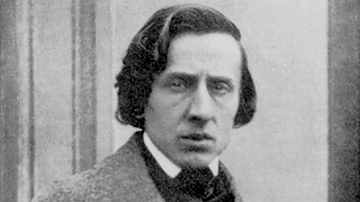

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849) was a Polish composer and virtuoso noted for his solo piano music. Chopin's work helped make the piano the most popular musical instrument of the 19th century. One of the great composers of Romantic music, Chopin's piano style, with its strong emphasis on single notes and great variations in speed, was a break from traditional keyboard playing.

Chopin's compositions, particularly their often idiomatic and thoroughly modern style – regarding both keys and pedals – play on the emotions of the listener and influenced many later composers from Franz Liszt (1811-1886) to Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943). Chopin was described by the famed 20th-century pianist Artur Rubinstein (1887-1982) as "the first composer who made the piano sing" (Siepmann), and this was perhaps his greatest contribution to the history of music, that is, to leave behind the old conventions and release the full potential of the piano as a truly versatile instrument.

Early Life & Influences

Frédéric Chopin was born in the village of Żelazowa Wola near Warsaw, Poland, on 1 March 1810. His mother, Justyna Krzyżanowska, was Polish and his father, Nicholas Chopin, was a French migrant who earned a living as a private tutor; in these two aspects, the son would follow the father. Frédéric (or Fryderyk as it would have been spelt then) had one older and two younger sisters. In 1811, the family moved to Warsaw. Frédéric composed music from the age of seven and performed in public from the age of eight. He studied under Adalbert Zywny (1756-1842) but was, to some degree, self-taught in his approach to piano playing, an approach which could include such unconventional techniques as playing black keys with his thumb. In 1825, Chopin played before Tsar Alexander I of Russia (r. 1801-1825) when he officially opened the Polish parliament. The Russian emperor gave Chopin a diamond ring after his performance.

When he was 16, Chopin joined the Warsaw Conservatory where he studied composition under Józef Elsner (1769-1854), to whom he dedicated his first piano sonata in 1828. Chopin excelled at his studies, graduating in just three years. In August 1829, Chopin briefly moved to Austria where he performed private concerts for the local aristocracy and gave a successful public performance at Vienna's Kärntnertor Theatre.

Back in Warsaw, Chopin dedicated himself to composition rather than performance, and he wrote his two piano concertos (1829-30). His style of composing is summarised by J. Samson in the following remarks in his essay on Chopin in The New Oxford Companion to Music:

His compositions rarely ventured beyond the world of the piano, for he drew much of his inspiration directly from the exploration of its sonorities, translating into its idiomatic language gestures culled from symphonic and operatic literature as well as from popular and folkloristic materials. (378)

Well-received by the public and critics, Chopin built on the success of his concertos by touring Central Europe, playing in Breslau, Dresden, and Prague in 1830, and then Vienna in the spring of 1831. Performing his own work in Vienna, Chopin drew praise from the critics in this city of great musical heritage. The pianist impressed with his new style of playing and his skill at improvisation. Samson summarises the pianist's flair as follows: "Contemporary accounts of his playing stress its lyrical, flowing quality, the remarkable delicacy of his touch, and the subtlety of his dynamic shading and pedalling" (378).

Chopin's planned concert tour of wider Europe had to be curtailed because of the Polish Insurrection when nationalists unsuccessfully attempted to rid the country of their Russian rulers. The revolution was ongoing, but when Warsaw fell into Russian hands in September 1831, Chopin (at least according to tradition) responded with his Étude Op. 10, No. 12, which became known as the "Revolutionary" Study. It is often considered the first mature work of Chopin in that he had now established his own unique composing style where there is a consistent quality of subtle tone (for him the most important musical quality of all) which contrasts with fast and intricate finger work.

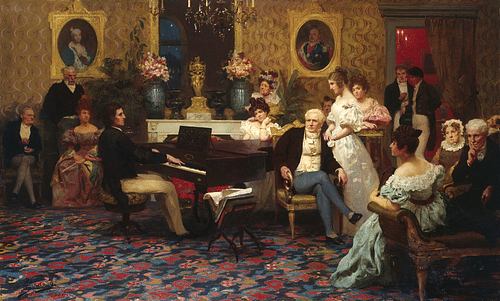

Towards the end of 1831, Chopin relocated to Paris, then the musical capital of Europe. Here he performed for and gained celebrity status amongst the wealthy, if not the paying public in concerts (throughout his career Chopin avoided larger, less intimate audience halls where the effects of his delicate style of playing could be lost). He did publish his music with success, and he earned a not insignificant income through teaching. Chopin charged the considerable sum of 20 francs a lesson (more than a week's wages for a factory worker at the time), and this allowed him to maintain a servant and carriage and to wear the fine clothes he was fond of wearing.

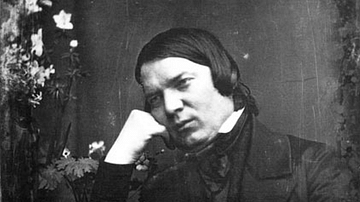

Chopin, through his private performances in influential circles and by publishing his music soon came to the attention of such figures as the composer Robert Schumann (1810-1856) who remarked on Chopin's arrival on the music scene in his popular musical journal. Schumann exclaimed: "Hats off, gentlemen, a genius!" (Thompson, 112)

Character & Relationships

The music historian C. Shonberg gives the following summary of Chopin's character and physique:

He liked to move in aristocratic circles, and was greatly concerned with style, taste, clothes and bon ton. He could be witty, malicious, suspicious, ill tempered, charming. There was something feline about Chopin…Short, slim, fair-haired, with blue-grey (some say brown) eyes, a prominent nose, and an exquisite bearing, he was physically frail…

(196)

Chopin was prone to mood swings, and although he is now regarded as one of the greatest composers of Romantic music (see below), he was not particularly romantic regarding his art, preferring, for example, not to give his pieces emotional or descriptive titles but rather a straightforward type and number. In the art circles of Paris, Chopin became friends with other noted Romantic composers like Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791-1864), Hector Berlioz (1803-1869), and Franz Liszt (1811-1886). Chopin also struck up a friendship with the painter Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863). It was not artists, though, that Chopin usually sought the company of, but higher society. In an 1833 letter home to Poland, he proudly declared, "I have found my way into the very best society. I have my place among ambassadors, princes, ministers" (Schonberg, 200).

From 1834, Chopin's work appeared in Neue Leipziger Zeitschrift für Musik, an influential music magazine founded by Robert Schumann. This period was also when Chopin wrote the first of his four ballades (lengthy romantic or poetic pieces). Schumann described the G minor ballade as the "most spirited and daring of Chopin's early works" (Sadie, 220). Schumann, after coming to know more of Chopin's music, memorably described it as "cannon buried in flowers" (Schonberg, 198).

From 1835, Chopin was romantically involved with Maria Wodzińska, a Polish emigré living in Paris. The relationship almost led to marriage in 1837 but, in the end, came to nothing, probably because Maria's parents did not approve of a pianist and Chopin's rather weak health. Chopin then had a brief relationship with the Polish countess Delfina Potocka, one of his many aristocratic piano pupils.

George Sand & Mallorca

A third relationship was more lasting, this time with the novelist Aurore Dudevant (1804-1876), better known by her pseudonym George Sand under which she wrote sensationalist novels. In 1838, the couple and Dudevant's two children relocated for a lengthy sojourn on the island of Mallorca. Staying in Palma, at first, the Mediterranean climate and scenery enchanted Chopin, who wrote in a letter, "The sky is like turquoise, the sea like emeralds, the air as in heaven" (Steen, 381). The trip, however, swiftly descended into a disaster and a series of endless rainy days that seriously compromised Chopin's health, although he still managed to compose his famous 24 preludes (a 25th has since been unearthed). Chopin, who had always had something of a cough in winters, was now showing symptoms of tuberculosis (then called consumption). At the time, this was considered a highly contagious disease, and so the couple were evicted from their villa and instructed to burn their clothes. Dudevant and Chopin relocated to a disused monastery at Valdemossa where they spent the next two months. Chopin had hired a piano, but the Pleyel piano he ordered never arrived, held up interminably in customs. The couple eventually moved on to Marseille, took a brief trip to Genoa, and then toured Provence in southern France where at least the weather improved if not Chopin's health.

Chopin and Dudevant remained together until 1847, spending four-month-long summers at Dudevant's family estate at Nohant near Bourges. Here, Chopin composed on his piano and Dudevant wrote her novels. Their relationship, for many years perhaps only a platonic one, was eventually soured by the interference of Dudevant's children from her marriage before she had met Chopin. Delacroix, who had a studio at Nohant, painted a double portrait of Chopin and Dudevant in 1838, a work which is today in the Louvre. After their separation, the pair of artists exchanged only one brief meeting for the rest of their lives.

Chopin's Style & Noted Works

Frédéric Chopin's major works include:

- 2 piano concertos

- 3 sonatas

- 4 scherzos

- 4 ballads

- 17 polonaises

- 19 nocturnes

- 25 preludes

- 27 études

- 19 waltzes

- 57 mazurkas

Chopin, at least in his earlier work, was clearly influenced by composers and fellow virtuoso players such as Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837) – particularly in regard to the early piano concertos and sonatas – Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826), and Friederich Kalkbrenner (1785-1849). Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) was another influence, seen most clearly in the use of contrapuntal techniques (combining two or more musical parts) in Chopin's preludes and studies. The second composer that Chopin was very fond of (and he liked very few others) was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791).

Chopin adopted the 'nocturne' form of music (short one-movement pieces meant to promote calm and reflection), first created by the Irish composer John Field (1782-1837). Chopin embellished the nocturne format to make it much more expressive. Another strong influence, best seen in the Nocturnes, came from the light and melodic singing style known as bel canto which was popular in 19th-century Italian operas, as here explained by the music historian J. Siepmann:

He realised that if melodies on the piano were to have the flexibility and expressivity of vocal lines, they would have to 'breathe' according to similar principles. In putting this perception into practice, aided by the pedals and a highly individual use of harmony, he created an entirely new kind of melody.

Chopin repeatedly incorporated elements of Polish folk dances like the lively mazurka and quick polonaise into his work. This may have been a deliberate strategy to promote the culture of Poland at a time when the country's existence was under serious threat from foreign powers. The melodies and rhythms of Polish folk music are most clearly evident in the finales of his piano concertos. Chopin only very occasionally strayed from his beloved piano and composed pieces for the flute and cello. Another area he explored was waltzes, although Chopin's are an idealised form and are not intended for dancing.

Chopin's mature composing style, which might inadequately be described as 'light' piano music, is more specifically defined by Samson in the following terms:

…a marked refinement of detail within prevailing melody and accompaniment texture, often involving a subtle mixture of ‘counterpoint' of fragmentary motifs, melodic, rhythmic, and textural…figurative patterns which imply a strong harmonic foundation while at the same time permitting linear-melodic elements to emerge through the pattern…increasingly close-knit, intricate textures… [and a] preference for unitary formal schemes - often a single impulse of departure and return.

(378-9).

Above all, in terms of musical history, Chopin was a composer of Romantic music (1790-1910), which is defined as follows by The New Oxford Companion to Music:

Romanticism emphasized the apparent domination of emotion over reason, of feeling and impulse over form and order…new value was set upon novelty and sensation, upon technical innovation and experiment, and upon the cross-fertilization of ideas from different disciplines, both within and without the arts. (1580)

Not all music critics have been enamoured by Chopin's work, some citing a weakness in his sense of form, although others have pointed out that Chopin deliberately reduced the form of his shorter pieces in order to emphasise their harmonic patterns. It is curious that Chopin suffered little or no criticism from his contemporaries. As Liszt noted, it was as if during his own lifetime, for Chopin, "posterity had already come" (Schonberg, 211).

Death & Legacy

From the mid-1840s, Chopin was increasingly ill with the effects of his tuberculosis, but this did not prevent him from making a tour of English and Scottish stately homes for private performances in the summer of 1848. One of his audience members was Queen Victoria (r. 1837-1901). Chopin's condition worsened, and his final public performance was to raise funds for Polish refugees in 1848. Chopin died of tuberculosis on 17 October 1849 in his apartment at 12 Place Vendôme, Paris. At his well-attended funeral in Paris, Chopin's famous Funeral March from the B flat minor Sonata was played along with Mozart's Requiem. A quantity of earth from Poland was added to the composer's grave in the Père Lachaise cemetery while his heart was sent to be interred in Warsaw's Church of the Holy Cross.

Chopin was instrumental in making the piano the favourite instrument of 19th-century music lovers. A whole army of minor composers drew inspiration from Chopin to create light musical pieces suitable for playing in the genteel salons of the well-to-do. More significantly, Chopin's style of idiomatic piano music had broken away from the more traditional style seen in the works of composers like Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827), and it greatly influenced Late-Romantic composers such as Franz Liszt (Chopin's lifelong friend), Claude Debussy (1816-1918), Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924), Richard Strauss (1864-1949), and Sergei Rachmaninoff. Debussy dedicated his own 12 Études to Chopin's memory, and the French composer once said that "Chopin is the greatest of us all; for through the piano alone, he discovered everything" (Siepmann).

Chopin's work continues to be immensely popular, connecting emotionally to audiences far beyond his own time. As Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) noted, "After playing Chopin, I feel as if I had been weeping over sins that I had never committed, and mourning over tragedies that were not my own" (Thompson, 112).