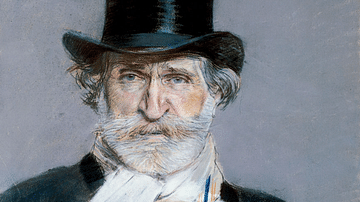

Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) was an Italian composer of around 40 operas, including the comic operas The Italian Girl in Algiers and The Barber of Seville. Rossini championed melody and beautiful singing over operatic drama, rattling out sensational hit after hit until his early retirement at 37. His innovative work was influential on those who followed, notably Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901).

Early Life

Gioachino Rossini was born in Pesaro in central Italy on 29 February 1792. His mother was a singer, and his father, Giuseppe, played the horn and trumpet for a living. As his parents frequently toured for their work, Gioachino was left in the care of his grandparents. Gioachino showed an early talent in music, playing the horn and keyboard, and singing; he even composed his own pieces. He went on to study music at the Academia Filarmonica of Bologna and, in 1806, at the Liceo Musicale, also in Bologna. He studied piano, the cello, and such technical features of music as counterpoint. His studies went well, and he won a prize in 1808 for a cantata.

When still only 15, Gioachino received his first opera commission and composed the single act Demetrio e Polibio (Demetrius and Polybius), which was performed privately in 1812. More public works followed, notably a series of farces for performance at Venice's Teatro San Moïse. These one-act shows included La scala di seta (The Silken Ladder) and Il Signor Bruschino (Mr Bruschino), staged in 1811 and 1813, respectively. In 1812, he composed the oratorio Ciro in Babilonia (Cyrus in Babylon), which was premiered in Ferrara.

Opera Successes

Rossini found work throughout the 1810s, rattling off comic and serious stage productions in Venice, Rome, Naples, and Milan. Three serious operas of note were Tancredi – his first international success and which had a libretto based partly on a work by Voltaire (1694-1778), Elisabetta, Regina d'Inghilterra, and Otello, act three of which Rossini considered his finest work (and which includes an innovative final murder). Rossini's name and fame spread; it was even said that the gondoliers of Venice sang songs from his operas, notably the aria Di tanti palpiti from Tancredi.

Four celebrated comic operas were L'italiana in Algeri (The Italian Girl in Algiers), Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville), La cenerentola (Cinderella), and La gazza ladra (The Thieving Magpie). In between his comic works, in 1815, Rossini took up the position of director of the Teatro San Carlo in Naples.

The two-act comic opera The Italian Girl in Algiers with a libretto by Anelli was first staged in Venice in 1813 and has remained popular in modern repertoires. Like later works, it mixed rapid farcical comedy with slower and much more serious moments, in this case, most notably the rousing patriotic song Pensa alla patria (Think of the Homeland).

The Barber of Seville is widely regarded as Rossini's masterpiece, although he seems to have written it in just two weeks. The two-act comic opera has a libretto by Sterbini based on a play by Beaumarchais (aka Pierre Caron), which was a prequel to The Marriage of Figaro by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791), first performed in 1786. The characters in Rossini's and Mozart's operas are the same. Rossini took the now famous overture from an earlier work, actually, three earlier works, such was its success.

The wily barber Figaro is the hero of the story as he conspires to ensure two young lovers – Count Almaviva and Rosina – escape the machinations of the aged Doctor Bartolo. Parts of the score imitate the tradition of 'patter songs' where a great quantity of words are squashed into as small a time as possible.

The opera received its premiere in Rome's Teatro Argentina on 20 February 1816 but was a disaster, thankfully, not because of the music but due to a number of mishaps on the stage – one cast member tripped on a trap door and was obliged to carry on despite a nosebleed, and a cat wandered across the stage. The opera became an international hit and was staged in London in March 1818 and in New York in May 1819. Giuseppe Verdi described it as "the most beautiful opera buffa there is” (Steen, 245).

Writing Style

Rossini was a fast writer, made possible because the genre was still quite formulaic, and because he moved around cities, he was able to recycle music from earlier work, knowing that his new audience had not heard the music before. He became so adept at writing operas that his approach bordered on the cavalier, as here he records in a letter to a fellow composer:

Wait until the evening before the opening night. Nothing primes inspiration more than necessity, whether it be the presence of a copyist waiting for your work, or the prodding of an impresario tearing his hair. In my time, all the impresarios of Italy were bald at thirty…I wrote the overture to La Gazza Ladra the day of the opening in the theatre itself, where I was imprisoned by the director and under the surveillance of the stagehands who were instructed to throw my original text through the window, page by page, to the copyists waiting below to transcribe it. In default of pages they were ordered to throw me out the window bodily. (Schonberg, 245)

Rossini cared little for the lyrics, once declaring: "Give me a laundry list and I will set it to music” (Schonberg, 246). No less a figure than Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) remarked on Rossini's speed: "Rossini is a man of talent and exceptional melodist. He writes with such ease that for the composition of an opera he takes as many weeks as a German would take years.” (Steen, 244)

Character & Family

Rossini "had genius, he had wit and sparkle…civilised, urbane, sharp-tongued, he was feared for his opinions, and his offhand remarks were gleefully quoted everywhere” (Schonberg, 246 & 250). Rossini was notorious as a gourmet and a chef. He often started the day off with a breakfast of two eggs, a glass of claret, and a cigar. He was once asked by a journalist whether it was true he had cried only twice in his life: once at the premiere of The Barber of Seville and once at a picnic when a delicious-looking stuffed turkey had accidentally rolled down the riverbank and been lost in the waters. Rossini replied to the question that twice was an exaggeration: "No, only once, and that was when the turkey fell in the river” (Wade-Matthews, 349). In another version of the same anecdote, Rossini is thought to have cried three times (the extra one was upon hearing the violin virtuoso Niccolò Paganini), but the turkey remains the only true episode worthy of the composer's tears.

Rossini was something of a chef, and he is credited with inventing the dish that now bears his name: tournedos Rossini (a cut of choice beef topped with a slice of foie gras). Food often found its way into his famously sharp witticisms: "I have just received a Stilton and a cantata from Cipriani Potter. The cheese was very good” (Schonberg, 250). He even gave some of his piano pieces titles like 'anchovies', 'radishes', and 'butter'.

Rossini married Isabella Colbran, a soprano singer, in 1822. Colbran had performed many of the leading roles in Rossini's operas. The couple lived in Bologna but became estranged. He married again after Colbran's death in 1845, this time to Olympe Pélissier, who had already been his long-term partner, in August 1846.

Superstar Fame

Rossini built on the success of The Barber of Seville and rolled out a succession of hits that made him an international superstar. He grew attached to Naples, and his operas often premiered in the city's Teatro San Carlo. Works staged in Naples included Mosè in Egitto (Moses in Egypt), La donna del lago (The Lady of the Lake), Maometto II, and Semiramide. Venice held an entire Rossini season of operas in the summer of 1822. One journalist memorably describes the scenes of adoration for Italy's most famous composer: "the entire performance was like an idolatrous orgy; everyone acted as if he had been bitten by a tarantula; the shouting, crying, yelling of "viva” went on and on” (Steen, 248). In 1823, Rossini took up the position of director of the Théâtre-Italien in Paris. In 1824, London staged seven Rossini operas. The composer had become the equivalent of a multi-millionaire pop star today. He continued to write operas, but he would, after one last hurrah, give up composing for the stage altogether in 1829.

The serious opera William Tell, with a libretto by Étienne de Jouy based on the adventures of the Swiss hero of the title, was to be Rossini's last. The story has Tell lead the Swiss against an Austrian army with a love story thrown in between Arnold, who is Swiss, and Mathilde, who is Austrian. William Tell was premiered at the Opéra in Paris on 3 August 1829. The four-act opera finished Rossini's career on a dramatic high with its spectacular combination of revolution, patriotic choruses, and ballet, all set in front of sumptuous scenery. William Tell toured the world, including runs in London and New York.

Rossini retired having earned great fame and wealth. He had no need to work anymore, suffered ill health (both mental and physical), and perhaps was disillusioned with the new direction music was taking. He once reacted to hearing the highly innovative Symphonie fantastique by Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) with a cutting: "What a good thing it isn't music” (Schonberg, 250). In 1837, Rossini returned to Italy but was back in Paris again in 1855. He did compose again several light pieces for the salon (Soirées musicales, 1835), several piano pieces which he called Péchés de vieillesse or "Sins of Old Age” (only published in the mid-20th century), and two sacred pieces. Rossini spent his retirement hosting hugely popular salons, where he played piano and entertained such famous names as Verdi, Franz Liszt (1811-1886), Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921), and Georges Bizet (1838-1875). The rooms of Rossini's villa on the edge of the Bois de Boulogne were packed during these evenings – guests knew opera's brightest star was in residence because he had a golden lyre hung on his gates. Rossini, now rather corpulent, would hold court, and the spectacle of all the ladies' diamonds on display was rivalled only by Rossini himself, wearing one of his famous wigs – he was said to have had a wig for each day of the week.

Influence on the Opera Genre

Before Rossini, opera in Italy had become rather stereotypical, with audiences demanding trifling spectacles that flashed brilliantly but then disappeared, never to be performed again. The singers were dominating opera, and composers were obliged to give them dazzling arias that allowed them to show off their vocal range and technique. Rossini was determined to change this state of affairs and create operas that could challenge those being written elsewhere. Rossini wanted to compose works that rivalled the operas of Mozart.

Rossini innovated by opening the performance with a rousing overture, using an expanded chorus, ensuring the chorus became an integral part of the story, eliminating unaccompanied recitative, using orchestral music instead of mere keyboard music, embellishing the arias, and giving a strong focus to characterisation. He developed the bel canto style, where "melodic line was underpinned by a simple but strong harmonic structure” (Sadie, 246). Rossini also greatly increased the pace of opera.

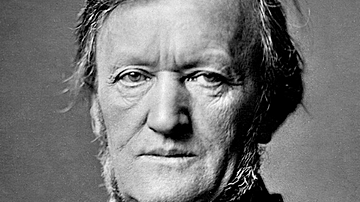

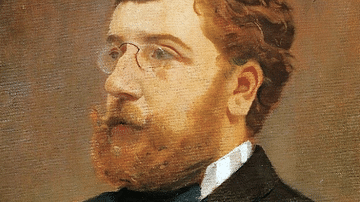

Rossini was an innovator in terms of orchestration. He was the first conductor to incorporate the valved trumpet into the orchestra, an instrument that had been invented in the 1820s. Rossini famously used the valve trumpet in William Tell; another unusual feature of that work is the bell employed in the second act. Some critics were appalled at some of these innovations, particularly Rossini's preoccupation with melody and dramatic sound effects. Richard Wagner (1813-1883) once noted that Rossini was a master of melody, but, in his opinion, his operas too often sacrificed drama on the altar of ear-pleasing tunes. Berlioz once lamented Rossini's use of "eternal puerile crescendo” and "brutal bass drum” (Sadie, 233). On the other side, Rossini had plenty of supporters, notably the author Stendhal (1783-1842), who went so far in his admiration to write a biography of the composer, Life of Rossini.

Rossini's Major Operas

The most important operas composed by Gioachino Rossini include:

Tancredi (1813)

L'italiana in Algeri – The Italian Girl in Algiers (1813)

Elisabetta, Regina d'Inghilterra – Elizabeth, Queen of England (1815)

Otello – Othello (1816)

Il barbiere di Siviglia – The Barber of Seville (1816)

La cenerentola – Cinderella (1817)

La gazza ladra – The Thieving Magpie (1817)

Armida (1817)

Mosè in Egitto – Moses in Egypt (1818)

La donna del lago – The Lady of the Lake (1819)

Maometto II (1820)

Semiramide (1823)

Il viaggio a Reims – The Journey to Reims (1825)

Le comte Ory – Count Ory (1828)

Guillaume Tell – William Tell (1829)

Rossini also composed such noted religious works as Stabat Mater (1842) and Petite messe solennelle (1863).

Death & Legacy

Rossini suffered ill health in his final years, including a stroke or similar calamity in 1866; he died in Paris on 13 November 1868. He was buried in Père Lachaise cemetery in the French capital. Rossini left a generous portion of his large fortune to his hometown of Pesaro with the directions that it be used to fund a conservatoire and home for retired musicians. In 1887, Rossini's remains were moved to Florence's Santa Croce church.

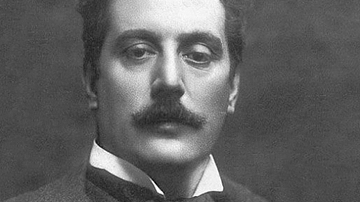

Rossini's work influenced the trio of Italian opera composers who followed soon after him: Gaetano Donizetti (1797-1848), Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835), and Giuseppe Verdi. Rossini had greatly helped the careers of the first two by promoting their works at the Théâtre Italien. Rossini also influenced many Spanish composers of zarzuela and French comic opera writers, notably François-Adrien Boieldieu (1775-1834). As Rossini retired from the public eye, his grand spectacle in William Tell went on to inspire Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791-1864) to redefine the opera genre and offer the insatiable public stage performances on an ever-grander scale. The new wave of opera composers built on Rossini's many musical innovations and forged on into a new era of Romantic music with more and more realistic but often tragic plots. Rossini's operas continue to be staged worldwide, and his rousing overtures are often performed as stand-alone pieces by concert orchestras. The finale of the overture to William Tell was famously used as the theme to the popular mid-20th century U.S. television show The Lone Ranger.