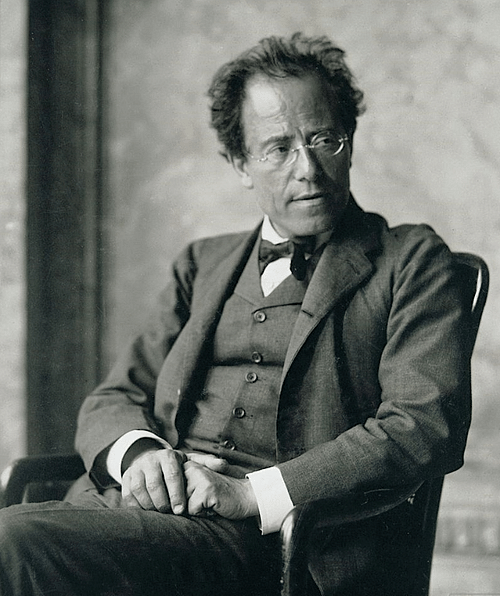

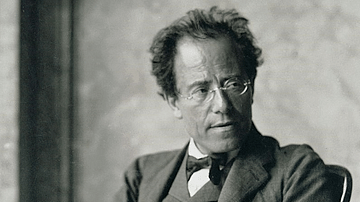

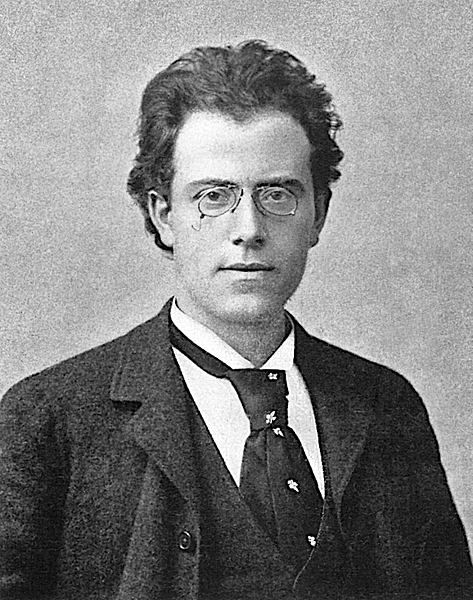

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) was an Austrian-Bohemian composer best known for his song-cycles and his grand, sweeping symphonies, which often require expanded orchestras for their full performance. Mahler, a composer of Late-Romantic music and conductor at such prestigious institutions as the Vienna State Opera and the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, died in Vienna, aged just 50.

Early Life

Gustav Mahler was born on 7 July 1860 in Kalište (Kalischt) in Bohemia, now in the Czech Republic but then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His father was Bernhard Mahler, who owned a distillery, and his mother was called Marie. Both of his parents were Jewish. Only a few months after Gustav was born, the family moved to Iglau (Jihlava) on the border of Bohemia and Moravia. Gustav had 13 siblings, and eight of these died while still children, a circumstance that may have affected his view on life as reflected in his later music.

Gustav's musical talent was obvious as a child, and he was encouraged by his family. He gave his first public performance, a piano recital, in Iglau in 1870. Gustav attended a boarding school in Prague in 1871, but this only lasted a year as he was badly treated at the school and so returned home.

A decisive moment came in 1875 when Gustav was given an audience with Julius Epstein, professor of piano at the prestigious Vienna Conservatory. Gustav's piano skills were reviewed, and he was enrolled in the Conservatory. During his studies, he won several piano competitions, but he preferred composition to performance. His earliest surviving work is a piano quintet, composed in July 1876. Neither were his studies limited to music since he attended courses in philosophy and history at the city's university. Mahler also found time to supplement his income by teaching piano.

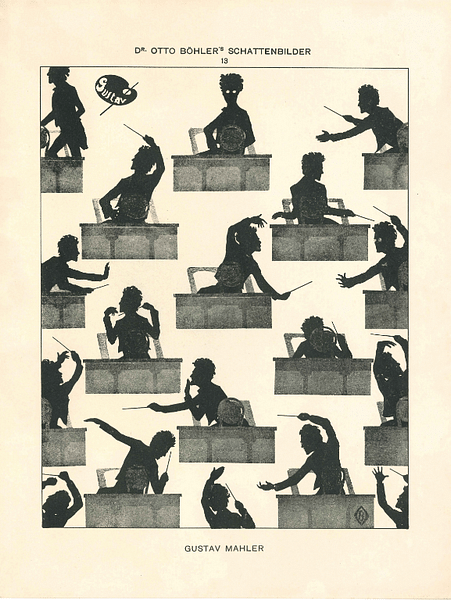

In Vienna, he composed and (unusually) also wrote the libretto (text) for Das klagende Lied ('The Song of Sorrow'), a cantata and his first major work. Mahler graduated in 1878 and found employment from 1880 as a conductor in minor theatres in various locations across the Austro-Hungarian Empire, including in Bad Hall in Upper Austria, Ljubljana in Slovenia, and Olomouc in Moravia. In this period Mahler, working his way up through larger and larger theatres, established a reputation as a master conductor of opera, but he was an exacting one, expecting exceptionally high standards from the singers he worked with. Mahler was swift to become enraged at any errors from his musicians and singers, and he could be brutal with his language, so much so, two rebuked performers once challenged him to a duel.

Character

The music historian C. Schonberg gives the following withering summary of Mahler's character:

He turned out to be austere, despotic, querulous, and arrogant, convinced of his moral and musical rectitude…he was a manic depressive with a sadistic streak. Musicians respected him but hated to play under his baton…He was nervous among people and had no small talk, none of the social graces…Mahler indeed put so much into music – as composer, conductor, administrator – that there was very little time for anything else. (509)

Mahler moved on to Kassel in Germany in 1883, where he began to compose his First Symphony and other works like Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen ('Songs of a Wayfarer'), an emotional song-cycle reportedly written to capture his feelings after a doomed love affair with a singer. Still something of a musical nomad, Mahler lived in Prague in 1885. He then moved on to Leipzig in 1886 where he continued to conduct. Here he completed the Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826) opera Die drei Pintos ('The Three Pintos'), which had been left unfinished. The work premiered two years later and helped build upon Mahler's growing international reputation.

From 1887, Mahler worked on setting folk poems to music, the poetry was taken from Des Knaben Wunderhorn ('The Youth's Magic Horn'), which he had discovered in a forgotten anthology of medieval poetry thanks to his contacts with the Weber family. A number of these poems were later incorporated into some of Mahler's symphonies.

The Master of Opera

That Mahler's star was rising was confirmed when he secured the prestigious role of conductor at the Royal Opera in Budapest in 1888, a position he would hold for three years. November 1889 saw the premiere of the composer's First Symphony, which he titled Symphonic Poem. Unfortunately, most of the critics did not appreciate it. In 1891, Mahler was back in Germany, this time conducting Tristan und Isolde, the opera by Richard Wagner (1813-1883). The work was performed through May at the Stadttheater in Hamburg. It was here that Mahler struck up a lasting friendship with the celebrated conductor Hans von Bülow (1830-1894), who described Mahler as a "first rate opera conductor" (Steen, 750). Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) witnessed Mahler's conducting and went even further than Bülow, describing the Bohemian as "a positive genius" (ibid). In 1892, Mahler briefly stayed in London, where he conducted at Covent Garden.

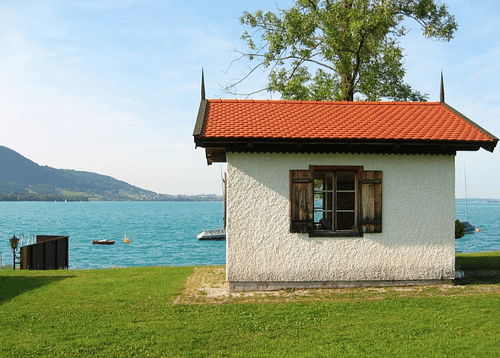

Mahler was now conducting in the summer months and composing in the winters, a routine he maintained for most of the rest of his career. A favourite haunt was his hut in Steinbach by Lake Attersee surrounded by the mountains of Upper Austria. When not composing, he spent a great deal of time walking, cycling, and swimming. Through the 1890s, he composed his Second and Third Symphony. The first performance of the Second Symphony, with Mahler conducting, was in 1895 in Berlin, and, unlike the First, it was a success and drew admiration from such musical celebrities as Richard Strauss (1864-1949).

In October 1897, Mahler was appointed the director of the Vienna State Opera, a position he held for a decade. The appointment came with the condition that he be baptized as a Catholic, a reflection of the rising antisemitism in Austria-Hungary in this period. Mahler agreed to the condition since he had long coveted the position. It is likely the composer did not privately renounce his Jewish faith, as he once described himself as "thrice homeless: as a native of Bohemia in Austria, as an Austrian among Germans, and as a Jew throughout the whole world" (Sadie, 287).

While in Vienna, Mahler moved the traditional conductor's podium to its now familiar position, facing both the musicians and performers on stage (previously the conductor saw only the stage performers with his back to the orchestra). The music historian Michael Kennedy in his essay on Mahler in The New Oxford Companion to Music notes that Mahler's time as conductor at the Vienna State Opera is "regarded as the zenith of that house's achievement…[with a] raising of standards in all aspects of opera production, not only singing, but acting, lighting, and stage design" (1118-9). In 1898, he was also appointed the conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, a post he held until 1901.

In the early 1900s, Mahler composed four more symphonies (4th to 8th), this time at a new retreat, Maria Wörth (Maiernigg) in Carinthia, southern Austria. Other works from this period include the epic song-cycles Rückert-Lieder ('Songs after Rückert') and Kindertotenlieder ('Songs on the Death of Children').

Marriage & New York

In March 1902, Mahler married Alma Schindler (1879-1964), the step-daughter of the artist Carl Moll. Alma was herself a composer, and it was through her influence and contacts that Mahler became involved in the Vienna Secession movement where a new style in art and music was championed over more traditional ideas. Mahler insisted that Alma give up her own composing when they married, and neither could she play piano in the house lest it disturbed her husband. Mahler did later have some of Alma's work published. The couple had two daughters, but their marriage was a strange one, with Mahler seemingly eternally betrothed to his music. As Alma once lamented, "I knew that my marriage and my own life were utterly unfulfilled" (Schonberg, 509).

1907 was a devastating year for the composer. In March, he was obliged to resign his position from the Vienna State Opera following a series of attacks in the press and by an antisemitic faction within the opera house. In the summer, his four-year-old daughter died of scarlet fever. It was also this year that Mahler's health began to decline. Doctors found that he had a heart complaint, specifically a defective valve.

In 1907, Mahler took up his new position as the conductor of the Metropolitan Opera House in New York; his first performance was Tristan, opening on New Year's Day 1908. Mahler conducted his Second Symphony at Carnegie Hall in Manhattan. He returned to Europe to compose as usual in his summer retreats. For the 1909-10 season, he became the conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

The Coming of the End

Mahler seems always to have been extraordinarily preoccupied with death, or rather, the temporary state of beautiful things and the meaning of life. His own deteriorating health did nothing to alleviate the distress that Mahler found while searching for eternal answers. Inspired by a series of Chinese poems on the shortness of life, he composed the six-movement Das Lied von der Erde ('The Song of the Earth') in 1908-9. In 1910, Mahler conducted with great success the premiere of his Eighth Symphony in Munich. Back to composing, there were still two more symphonies to work on.

Mahler's marriage was in a poor state, although he still dedicated the Ninth Symphony to Alma in 1909. As the relationship deteriorated to new depths, Mahler consulted Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) in Leiden in the Netherlands in 1910. The founder of psychoanalysis recognised Mahler as a "genius" but struggled to read his patient, noting, "No light fell at that time on the symptomatic facade of his obsessional neurosis. It was as if you would dig a single shaft through a mysterious building" (Schonberg, 510).

With nine symphonies complete, Mahler then fell victim to what some have called the 'curse of the ninth' where it is believed no composer can write a tenth symphony since, as the composer Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) put it, "Those who had written a Ninth Symphony were too close to the Beyond". The 'curse' may be nonsense, but it is a curious coincidence that several composers did not get past number nine, notably Ludwig von Beethoven (1770-1827), Franz Schubert (1797-1828), Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904), and Anton Bruckner (1824-96). Mahler himself was conscious of the idea since he could well have called his epic Das Lied von der Erde his ninth symphony but decided not to. In a letter to Alma, Mahler noted that "Das Lied von der Erde was really the Ninth" and when he completed it, he wrote with relief, "Now the danger is past." Sadly, this was not true, for Mahler died the year before his real Ninth Symphony premiered and before he could complete the orchestration of his Tenth Symphony.

Mahler's Noted Works & Style

The most famous works by Mahler, with their first performance dates, are:

- 10 Symphonies (1889-1964)

- Des Knaben Wunderhorn (1893)

- Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (1896)

- Das klagende Lied (1901)

- Rückert-Lieder (1905)

- Kindertotenlieder (1905)

- Das Lied von der Erde (1908)

Mahler's work as a Late-Romantic composer bridged the more traditional music of the 19th century with the more experimental music of 20th-century composers. He was influenced by the poetic folktales of his youth and by earlier composers, notably Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750), Beethoven – particularly his Ninth Symphony, Richard Wagner, and Johannes Brahms (1833-1897). Mahler's sweeping strings, avant-garde use of percussion instruments (take only the hammer blows at the finale of the Sixth Symphony), and unleashing of the full awesome power of an augmented symphony orchestra and bulked-up chorus rang in a new era of classical music.

Mahler once stated that "To write a symphony is, for me, to construct a world" (Wade-Mathews. 414). Symphonies 5, 6, and 7 employ a more restrained use of the orchestra and contain sections reminiscent of chamber music. In contrast, Symphonies 2, 3, 4, and 8 all contain massive choral sections. Mahler's Eighth Symphony, completed around 1907, was nicknamed the "Symphony of a Thousand". Written on a massive scale, the performance of the work required an expanded orchestra plus seven soloists, the voices of 350 children, and a 500-member adult chorus. The Eighth Symphony was inspired by a medieval text and Faust, the tragic play by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832). Mahler described the Eighth as "the greatest work I have yet composed" (Wade-Matthews, 415).

Mahler's work was not always appreciated by everyone during his own lifetime; the complexity of his symphonies, in particular, irritated some and perplexed others, but as the composer himself confidently declared, "My time will come" (Sadie, 286). The expressiveness and personal depth of Mahler's music are not always easily interpreted. Mahler himself explained why this may be:

As long as my experience can be summed up in words, I write no music about it; my need to express myself musically – symphonically – begins at the point where the dark feelings hold sway, at the door which leads into the 'other world' – the world in which things are no longer separated by space and time.

(Sadie, 286)

Death & Legacy

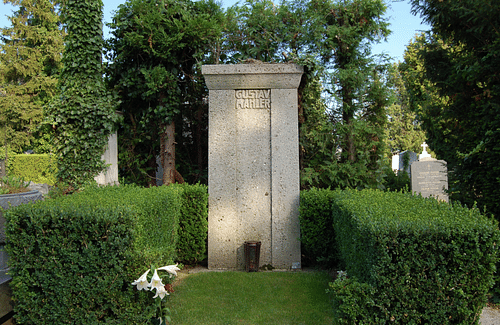

Mahler fell ill with a bacterial infection of the throat in February 1911 while in New York. He sought treatment in April in Paris, but doctors could not help. Gustav Mahler died in Vienna on 18 May 1911, he was just 50 years old. Mahler was buried next to his daughter in the cemetery in Grinzing, now a suburb of Vienna. At his request, the gravestone carries only two words: Gustav Mahler. He never saw the performance of his Ninth Symphony. The Tenth Symphony was ultimately orchestrated by Deryck Cooke, five decades after Mahler's death.

The sheer scale of Mahler's symphonies, where a large auditorium was required (and even the number of seats for the paying public had to be reduced) meant that many of them were not performed at all until a revival in the second half of the 20th century. Several composers were then keen to show the world the wonder of Mahler again. Notable amongst these admirers was Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) who, in the 1970s during the Cold War, when global nuclear destruction seemed imminent, pointed out that "ours is the century of death, and…Mahler is its musical prophet" (Kimberley). That Bernstein meant what he said was affirmed when he chose to conduct Mahler's Second Symphony on US television two days after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963.

Mahler's music lives on, of course, fully established in the classical music repertoire and influencing later composers, notably Alexander Zemlinsky (1871-1942), Anton Webern (1883-1945), and Benjamin Britten (1913-1976), amongst many others, but he has reached even wider audiences by other means, notably in film soundtracks. Most famously, and most appropriately given his concern with the transience of life, he exploded onto the world's attention once again when the 1971 film Death in Venice, directed by Luchino Visconti, significantly featured music by Mahler, notably the Adagietto of his Fifth Symphony and extracts from his Third Symphony. The film is based on the 1912 novella of the same name by Thomas Mann (1875-1955), but Visconti changed the main character from a writer to a composer, not only for the striking similarities with Mahler's own demise, perhaps, but also because this would permit the film to carry a more meaningful score. Mahler had dedicated the Adagietto to his wife Alma, and it was she who noted that, at the pinnacle of his career and fully aware of what he had achieved, Mahler "was conscious of the greatness of his work. He was a tree in full leaf and flower" (Osborne).