Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) was the leading French composer of Romantic music, best known for his innovative Symphonie fantastique and use of large-scale orchestras and choruses in works like The Trojans opera. Berlioz's innovative style brought successes and failures in equal measure, but his lasting legacy is that he dramatically changed what was thought possible in orchestral music.

Early Life & Influences

Louis-Hector Berlioz (usually referred to as Hector Berlioz) was born on 11 December 1803 in La-Côte-Saint-André near Grenoble in southeast France. Hector's father was a doctor, and he wanted his son to follow in his footsteps. However, on attending medical school in Paris, Hector could not stomach the more grisly aspects of 19th-century medicine. He left after two years of study, in his own words, "firmly resolved to die rather than enter the career that had been forced on me" (Schonberg, 160). He duly changed career path and decided to pursue music.

Hector had learnt only guitar and the flute as a child, but he had sent off some of his own compositions to a Paris publisher. Now he returned to his real passion. He took private lessons in composition with Jean-François Le Sueur (1760-1837) and Antoine Reicha, who had once worked alongside Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827). Berlioz watched countless operas, often shouting out from his free student seat when he thought something was amiss with the orchestration. Berlioz then went on to study at the Paris Conservatoire from 1826 until 1830.

Berlioz only ever mastered the guitar and flute as a player. Unlike the vast majority of great composers, he could not play the piano, but he saw this as an advantage. Berlioz once stated that his lack of knowledge of the usual tool of the composer "has delivered me from the tyranny of the fingers," and so he was "grateful to the happy chance that forced me to compose freely and in silence" (Schonberg, 158).

Berlioz's skills in composition and orchestration, however, were obvious. He was a fan of Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826), once describing his reaction to the German Romantic's music in these terms: "Weber, who seems to whisper in my ear like a familiar spirit, inhabiting a happy sphere where he awaits to console me" (Wade-Matthews, 352). Berlioz even orchestrated Weber's Invitation to the Dance (Aufforderung zum Tanz), a piece for piano. Another early influence was Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787), and a more lasting one Beethoven. Berlioz was, though, something new in the world of music. He created the expanded, modern orchestra. He "was the first to express himself autobiographically in music, bringing a new dimension to the psychology of the art." Further, he "broke away from the classic rules of harmony to explore hitherto forbidden chord progressions and an entirely new kind of melody" (Schonberg, 158-9).

Berlioz eked out a modest living by teaching guitar to private students and singing in a theatre chorus in Paris (this was part of a vaudeville troupe and was such a blow to his higher musical aspirations that he did not tell his friends about it). Berlioz's career was launched in 1830 when he won, after four previous attempts, the prestigious Prix de Rome with a cantata. The prize included a five-year scholarship, two years of which were to study at the French Academy in Rome. The young composer spent 15 months in Italy before returning to Paris, ignoring the stipulation of the prize that he study a third year in Germany. Above all, Berlioz wanted to prove himself in Paris.

Character & Family

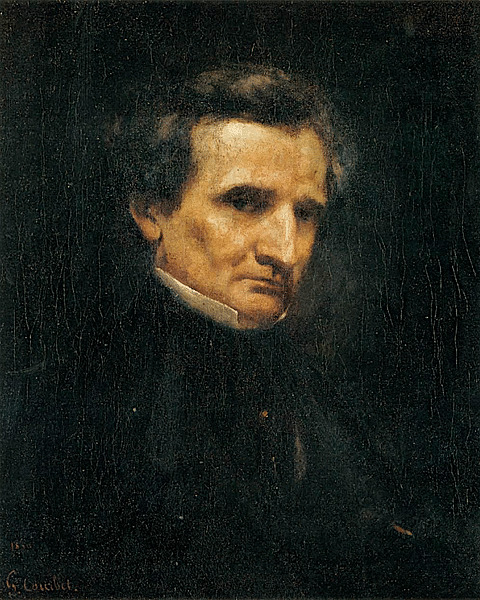

Berlioz had a high forehead, hawk-like nose, and a mass of hair that one contemporary described as "like an enormous umbrella" (Schonberg, 162). Sensitive, passionate, and impulsive by nature, Berlioz was prone to violent emotions" (Wade-Matthews, 356). Another music historian gives a similar portrait:

He was an enthusiast, a natural revolutionary, the first of the conscious avant-gardists…Uninhibited, highly emotional, witty, mercurial, picturesque, he was very conscious of his Romanticism. He loved the very idea of Romanticism: the urge for self-expression and the bizarre as opposed to the Classic ideals of order and restraint.

(Schonberg, 159)

In 1827, Berlioz fell in love with the Irish actress Harriet Smithson, whom he saw in a performance of Hamlet in Paris. Utterly besotted despite never meeting her off the stage, Berlioz called the famous actress ‘la Belle Irlandaise'. Harriet at first rebuked the composer's advances, ignoring his letters and shunning performances of his music, but his persistence paid off, and they did eventually marry in October 1833. The couple lived in Montmartre, but the marriage was not a success. Harriet drank excessively, and Berlioz was largely absent from home life and his young son, Louis. From 1841, Berlioz took a mistress, the singer Marie Recto. From 1844, Berlioz and Harriet no longer lived together. Following a series of incapacitating strokes, Harriet died in 1854; Berlioz then married Marie.

Symphonie fantastique

The Symphonie fantastique masterpiece was composed in 1830. Berlioz explained to his listeners in words what his innovative music meant. The Symphonie fantastique is a five-movement symphony, which the composer gave the subtitle "Episodes in the life of an artist". Berlioz wanted all of his music to be understood, and so he gave each of the movements suggestive titles. For example, the fourth movement, an extravaganza of brass and drums, is called March to the Scaffold and reflects the imaginings of an opium addict artist who, in a drug-induced dream, believes that he has killed his lover and is about to be led to the guillotine for his crime. The melodic motif or idée fixe that is heard throughout the symphony, but most distinctly in the first three movements, represents the artist's "beloved". The final movement represents a Witches' Sabbath, and the "beloved" is transformed into an old woman, represented musically by the distortion of her melodic theme. The tumultuous relationship of the protagonists perhaps reflects Berlioz's own real-life obsession with Harriet Smithson. Symphonie fantastique was premiered on 5 December 1830 in Paris at the Salles des Concerts du Conservatoire. Berlioz had programmes explaining the story handed out to the audience as they came in. This was not perhaps the first example of ‘programme music' (where music is given a specific story), but it was the boldest.

Innovative Instruments

Berlioz was an ambitious composer, his perfect orchestra would have contained 465 players, but this was never realised in practice. Most orchestras of the day had 60 players, while Berlioz often assembled 150 musicians. His Requiem includes the need for 16 timpani (aka kettledrums) to ring a chime, while Grande Messe des Morts contains a passage employing ten cymbals. Symphonie fantastique was the first symphony to include the harp. Berlioz also sometimes favoured more neglected instruments; he wrote, for example, Harold en Italie, which was a symphony with viola obbligato. Inspired by his time in Italy, the symphony was commissioned by the virtuoso player Niccolò Paganini (1782-1840), although in the event he thought it did not sufficiently utilise the full repertoire of his talents.

Berlioz was a fan of both the flute and trumpet, considering both instruments to have a beautiful quality of tone. The new sounds made possible by new instruments intrigued Berlioz. When orchestral tubas were invented in 1835, Berlioz asked his publishers to have them replace the ophicleides in Symphonie fantastique. Berlioz's imagination could also stretch in the other direction and seek out instruments now lost. For his Romeo et Juliette symphony, he had a pair of cymbals made based on those found in the ancient Roman city of Pompeii. Berlioz's penchant for exotic instruments and large orchestras was often parodied in the Parisian popular press.

Critical Reaction

Some critics (then and now) take Berlioz's originality only as a reflection of his lack of composing skills. Fredéric Chopin (1810-1849), although a friend, was not impressed with Berlioz's style, once noting acidly, "Berlioz composes by splashing his pen over the manuscript and leaving the issue to chance" (Wade-Matthews, 356). Others did not agree. Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) and Franz Liszt (1811-1886) were both staunch supporters of Berlioz. Certainly, his "idiosyncratic style, embracing irregular rhythms and phrases, contrapuntal textures and imaginative orchestration, was not appreciated" by all (Schonberg, 160).

Berlioz paid the price for his innovation and struggled to make a living only from his compositions. There were some hits and misses, often depending on location. For example, the cantata-like La damnation de Faust was not appreciated in Paris but received great acclaim in Russia. Even parts of a single piece received a mixed reaction. His 1838 opera Benvenuto Cellini, when staged in Paris, was a failure, but the public loved (and still does) the rousing overture Le carnival romain (Roman Carnival). As a consequence of the financial failures of his work, Berlioz was obliged to write music reviews; he could be a witty but scornful reviewer. The composer did not like the journalistic side of his career, but the noted music historian and Berlioz specialist H. MacDonald remarks that "he was one of the most perceptive and vital writers of his time" (Arnold, 213).

Berlioz also made tours conducting, performing between 1842 and 1862 in Austria, Belgium, England, Germany, and Russia. Berlioz was a physical conductor, "a volatile and extravagant figure on the podium, one of the first choreographic conductors" (Schonberg, 174). The composer's reputation was always higher away from Paris, particularly as a conductor.

The composer kept on composing, and he never gave up on Paris, despite his view that "Parisians have become a barbarous people" (Steen, 323). His faith was rewarded with the success of his choral trilogy L'enfance du Christ in 1854 and a prestigious commission for music at the 1855 Universal Exhibition, his Te Deum. French audiences remained fickle, though, and he was particularly stung by the lack of success of his epic five-hour opera The Trojans, not staged until 1863, and then only a butchered second part, Les Troyens à Carthage. The opera was based on the work of the ancient Roman author Virgil (70-19 BCE), and it had taken several years to compose. Once again, the real success came abroad, this time with a production of Berlioz's comic opera Béatrice et Bénédict staged in Baden-Baden in Germany in 1862. The opera continued the composer's lifelong attraction to the works of William Shakespeare (1564-1616) as it was based on Much Ado About Nothing.

Berlioz's Major Works

The most famous works by Hector Berlioz include:

Symphonie fantastique (1830)

Le corsaire (The Pirate) – overture (1831)

Harold en Italie – symphony (1834)

Benvenuto Cellini – opera (1834-8)

Grande messe des morts (1837)

Roméo et Juliette – choral symphony (1839)

Grand symphonie funèbre et triomphale – for a military band (1840)

Les nuits d'été (Summer Nights) – song-cycle (1841)

Le carnival romain (Roman Carnival) – overture (1844)

La damnation de Faust – choral work & opera (1846)

Te Deum (1849)

L'enfance du Christ (The Childhood of Christ) – oratorio (1854)

Les Troyens (The Trojans) – opera (1856-8)

Béatrice et Bénédict – comic opera (1862)

Berlioz also wrote an important treatise on orchestration in 1843, which was translated into English in 1855, and a handbook on conducting, published in 1855.

Death & Legacy

Berlioz suffered from depression and other health problems in his later years, notably acute intestinal neuralgia, which required him to take opium. In June 1867, his only son died. Berlioz had paid for Louis to train for the navy, but this profession was a dangerous one, and he died of fever in Cuba. More often than not housebound, Berlioz called his small apartment Caliban's Cave in reference to the half-monster, half-human character of that name from Shakespeare's The Tempest. He continued his passion for reading, his particular favourites being Byron, Virgil, and Shakespeare. He once said, "I have spent my life with this race of demigods; I know them so well that I feel as if they must have known me" (Schonberg, 172). Hector Berlioz died in Paris on 8 March 1869. Berlioz, in effect, wrote his own biography, published as Mémoires in 1870, although it is far from being an entirely objective account where truth is sometimes sacrificed for entertainment.

Berlioz had a particularly individual musical style, but he perhaps most directly influenced the Czech composer Bedrich Smetana (1824-1884). Berlioz's innovations were certainly studied by others, notably Franz Liszt, Richard Wagner (1813-1883), Richard Strauss (1864-1949), and Gustav Mahler (1860-1911), amongst others. As the historian H. C. Schonberg notes about Berlioz:

He had no direct followers, for his ideas were too unorthodox for his immediate contemporaries; but later composers did absorb his message, and his influence extended to every sector of the musical avant-garde. (159)

Berlioz remains a divisive figure for critics, but his position amongst the great composers is assured since "his interest in new and varied modes of expression and his passionate sense of colour and drama embodied the Romantic ideal" (Sadie, 214). Schonberg goes further: "Almost single-handedly he broke up the European musical establishment. After him, music would never be the same" (160).