Kamakura is a coastal town located on Sagami Bay on Honshu Island, Japan, which was the capital of the Kamakura Shogunate from 1192 to 1333 CE. Provided with excellent natural defensive features, it was fortified and made the base of the Minamoto clan and then the Hojo shoguns. Several important Buddhist temples were built at the site such as the Kenchoji, and there still remains today the massive bronze Buddha that once belonged to the 13th-century CE Kotokuin temple. The city fell with the Kamakura Shogunate when it was attacked and destroyed by an army of rebel samurai led by Nitta Yoshisada c. 1333 CE.

Minamoto no Yoritomo

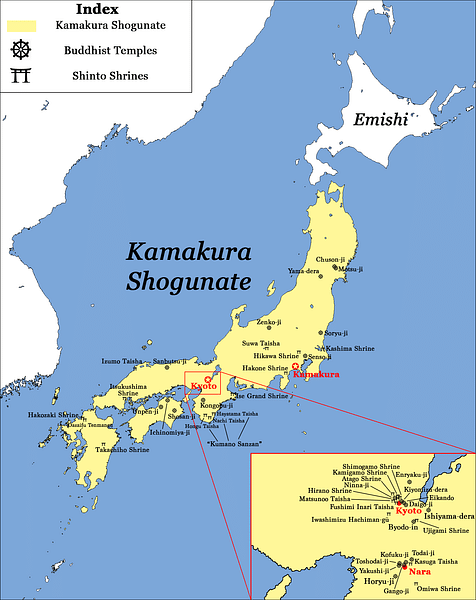

Kamakura is located 48 kilometres (30 miles) southwest of Tokyo (formerly known as Edo) on the east coast of Honshu Island in Kanagawa Prefecture. It was nothing more than a fishing village before it was given a new grandiose role in the medieval period, although the Kojiki, Japan's oldest book compiled in 712 CE, does make a brief mention of 'the lords of Kamakura.' Kamakura really rose to fame when it was used as the base for the powerful Minamoto clan which dominated Japan in the last quarter of the 12th century CE until the first quarter of the 13th century CE when they were superseded by the Hojo clan. Even then, it continued to be the capital of the shoguns (military dictators) for another century or so.

Minamoto no Yoritomo, shogun of Japan from 1192-1199 CE and founder of the Kamakura Shogunate (1192-1333 CE) selected Kamakura as a safe place for his new capital in 1192 CE. The site was well protected by mountains on three sides and the sea on the fourth side. A large tunnel was excavated through the relatively soft rock, the Shakado tunnel, which provided a handy escape through the mountains if required. Ever wary of a rival warlord or rebellion in the militaristic political landscape of medieval Japan, Yoritomo ensured Kamakura was given much more protection than nature provided. First, the mountains behind the city were further fortified with a long series of earthworks defensive walls (which can still be visited today). Next, two wooden stockade castles were added: Sugimoto and Sumiyoshi. Sugimoto was built right in the heart of Kamakura while Sumiyoshi was erected at the eastern end of the beach. The only other thing needed was to carve out more open space for the enlarged city, a process that caused much deforestation in the area.

Kamakura had another advantage in that it was suitably distant from the court intrigues and potential disloyalties at the imperial court at Heiankyo (Kyoto). Yoritomo's choice would give the name to this particular period of Japanese medieval history: the Kamakura period (1185-1333 CE). The result of having, in effect, two capitals separated by 10 days travel was that Japan improved its road system and commerce and the arts were no longer restricted to the Heiankyo area. Yoritomo himself made regular trips to Heiankyo where the imperial court remained the heart of aristocratic Japan and where the city's officials continued to dispense titles, collect certain taxes, and preside over civilian judicial disputes. Heiankyo also remained the artistic centre of Japan although Kamakura did attract some artists and excelled, in particular, in such minor arts as gilded lacquerware. There was even a distinctive variety, the Kamakura-bori, which displays designs in very high relief, stained in red. Fine examples can be seen today in the Kokuho-kwan Museum in Kamakura which boasts 50 National Treasures of Japan.

Religious Buildings

Unfortunately, Kamakura does not have much today by way of architecture to remind of the city's importance in the 12th and 13th centuries CE, but there were some fine religious buildings befitting its status as the shogun's capital.

During the Kamakura period two significant new sects of Zen Buddhism were developed; the Jodo Sect (aka Pure Land) and the Jodo Shin Sect (aka True Pure Land). Both sects simplified the religion and stressed that simply chanting the Buddha's name (nembutsu) would permit a person of any social class to be reborn in the Amida Buddha's Pure Land paradise. Naturally, Kamakura, therefore, required its own Zen temple.

The most important Zen monastery was the Kenchoji, founded by the Chinese monk, Rankei Doryu (aka Lanqi Daolong) and funded by the regent Hojo Tokiyori (l. 1227-1263 CE) between 1249 and 1253 CE. The Kenchoji temple shows influence from Chinese architecture - large communal halls and elaborate gates - and is said to have been a copy of the layout of the Zen (Chan) headquarters at Hangzhou. The connection should not be surprising considering the faith's links with China and the fact that Chinese monks frequently came to study at Kamakura as they fled the Mongols in the 13th century CE. Kenchoji temple even had three Chinese abbots, including its first, the monk Doryu.

The Kotokuin Temple was built in 1252 CE. Unfortunately, a great earthquake c. 1495 CE caused a tsunami tidal wave which completely washed away all the temple structures. What remained, largely thanks to its weight of over 93 tons, was the Daibutsu, a giant statue of Amida or Great Buddha. It was cast in bronze by the master founder Tanji Hisa-tomo who made it in many individual sheets which were then soldered together. Although never rehoused since the fateful tsunami, the Buddha still pulls in visitors today eager to see this towering figure which, sitting on a massive stone platform, rises 11.3 metres (37 ft) high. The face alone is 2.3 metres (7.5 ft) by 4.5 metres (14.5 ft). The figure must have been even more impressive in the 13th century CE because it was originally gilded, traces of which can still be seen on the Buddha's cheeks. The figure is hollow and visitors can peek inside this marvel of bronze casting.

Another important Zen temple, indeed, today the most important in Japan, was the Engakuji monastery, established c. 1283 CE by Hojo Tokimune, the regent shogun (r. 1268-1284 CE) and the Chinese monk Mugaku. The two-storey Shari-den building, the only original structure at the site, is thought to enshrine a tooth of the Buddha brought to Kamakura from China. The temple's fine bronze bell is listed as an official National Treasure of Japan. The bell was donated to the temple in 1301 CE by Hojo Sadatoki, the regent shogun (r. 1284-1311 CE).

The Shinto Tsurugaoka Hachiman Shrine (Tsurugaoka Hachimangu) was built by Minamoto no Yoriyoshi (l. 988-1075 CE) in 1063 CE but was moved from its location at Yuinogo to Kamakura in 1191 CE by Minamoto no Yoritomo. Hachiman is the Shinto god of war, and he was considered the protective deity of the Minamotos long before the Kamakura Shogunate. The shrine is also dedicated to two semi-legendary rulers: Empress Jingu and her son the deified Emperor Ojin (r. 270-310 CE); both of whom were thought to have been avatars of Hachiman, such were their great feats in warfare and culture in general - Jingu for invading Korea, and Ojin for inviting Chinese and Korean scholars to Japan. Another figure is also worshipped at the shrine, Hime Okami, the wife of Ojin. There is a festival famous for its archery contests held at the shrine each September.

Attack & Decline

Kamakura's defences would be needed when the city came under siege in 1333 CE at the end of the Kamakura period. In these troubled times, when the shogunate was weakened by a lack of finances and many samurai were restless for paid employment, Emperor Go-Daigo (r. 1318-1339 CE), eager for more power, stirred up rebellion. One of the emperor's allies, Nitta Yoshisada (l. 1301-1337 CE), attacked Kamakura c. 1333 CE, and his fellow rebel warlord, Ashikaga Takauji, attacked Heiankyo as the new regime swept away the old.

At first, Kamakura's natural defences and additional fortifications did their job and kept the besiegers out, but Yoshisada had his army go around the adjoining Inamuragasaki cape at the western end of the beach at low tide. Thus, the rebels could attack the city from the less-protected beach side. In July, the city fell and was torched. Rather than risk capture, the last leaders of the Hojo clan committed ritual suicide, ironically near a Buddhist temple called the 'temple of victory.'

Ashikaga Takauji would become the new shogun in 1338 CE, thus inaugurating the Ashikaga Shogunate (aka Muromachi Shogunate, 1338-1573 CE). The capital was moved back to join the imperial court of Heiankyo and so Kamakura fell into decline thereafter. The Ashikaga shoguns appointed a governor-general to keep an eye on Kamakura and the region in general lest a Hojo resurgence occur, but otherwise, the town did not receive very much attention until the Edo period (1603-1868 CE) when some investment was made by the government in its remaining culturally important buildings.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.