The word labyrinth comes from the Greek labyrinthos and describes any maze-like structure with a single path through it which differentiates it from an actual maze which may have multiple paths intricately linked. Etymologically the word is linked to the Minoan labrys or 'double axe', the symbol of the Minoan mother goddess of Crete, although the actual word is Lydian in origin and most likely came to Crete from Anatolia (Asia Minor) through trade.

Labyrinths and labyrinthine symbols have been dated to the Neolithic Age in regions as diverse as modern-day Turkey, Ireland, Greece, and India among others. In the Tantric texts of India, the labyrinth is often featured in the design of mandalas while in Britain and Ireland they are pre-figured in the ring-and-cup marks often found in stone work and the famous swirl designs found at sites such as Newgrange.

The labyrinth has been defined as distinct from the maze in that, as noted above, a labyrinth typically has a single path which winds through it while a maze can have many. Even so, the terms labyrinth and maze are often used interchangeably. The scholars Alwyn and Brinley Rees discuss the significance of the labyrinth-maze and why the design seems to have resonated so strongly with ancient people, specifically the Celts:

Much has been written during the past three decades about the ritual significance of mazes, both as a protection against supernatural powers and as a path which the dead must follow on their way to the world of the spirits. Here we will simply note that mazes are in relation to directions what betwixts-and-betweens are in relation to opposites. In passing through a maze one is not going in any particular direction, and by so doing one reaches a destination which cannot be located by reference to the points of the compass. According to Irish folk-belief, fairies and other supernatural beings can cause a man to lose his bearings…it is when the voyagers have lost their course and shipped their oars – when they are not going anywhere – that they arrive in the wondrous isles. (346)

The labyrinth/maze, then, may have served to help one find their spiritual path by purposefully removing one from the common understanding of linear time and direction between two points. As one traveled through the labyrinth, one would become increasingly lost in reference to the world outside and, possibly, would unexpectedly discover one's true path in life. The theme of the labyrinth leading to one's destiny is most clearly illustrated in one of the best-known stories from Greek mythology: Theseus and the Minotaur.

The Labyrinth of Crete

The most famous labyrinth is found in Greek mythology in the story of Theseus, prince of Athens. This labyrinth was designed by Daedalus for King Minos of Knossos on Crete to contain the ferocious half-man/half-bull known as the Minotaur. When Minos was vying with his brothers for kingship, he prayed to Poseidon to send him a snow-white bull as a sign of the god's blessing on his cause. Minos was supposed to sacrifice the bull to Poseidon but, enchanted by its beauty, decided to keep it and sacrifice one of his own bulls of far less quality. Poseidon, enraged by this ingratitude, caused Minos' wife Pasiphae to fall in love with the bull and mate with it. The creature she gave birth to was the Minotaur which fed on human flesh and could not be controlled. Minos then had the architect Daedalus create a labyrinth which would hold the monster.

Since Minos was hardly interested in feeding his own people to the creature, he taxed the city of Athens with tribute which included sending seven young men and maidens to Crete every year who were then released into the labyrinth and eaten by the Minotaur. Daedalus' labyrinth was so complex that he, himself, could barely navigate it and, having successfully done so, Minos imprisoned him and his son, Icarus, in a high tower to prevent him from ever revealing the secret of the structure. Later, in another famous tale from Greek mythology, Daedalus and Icarus escape their prison using the feathers of birds bound together by wax to form wings with which they fly from the tower. Icarus flew too close to the sun, melting the wax of his wings, and fell into the sea where he drowned.

Prior to their flight, however, Athens was annually sending the 14 young people to Crete to be killed in the labyrinth until Theseus, son of King Aegeus, vowed to put an end to his people's suffering. He volunteered as one of the tributes and left Athens in the ship with the traditional black sails hoisted in mourning for the victims. He told his father that, should he be successful, he would change the sails to white on the trip home.

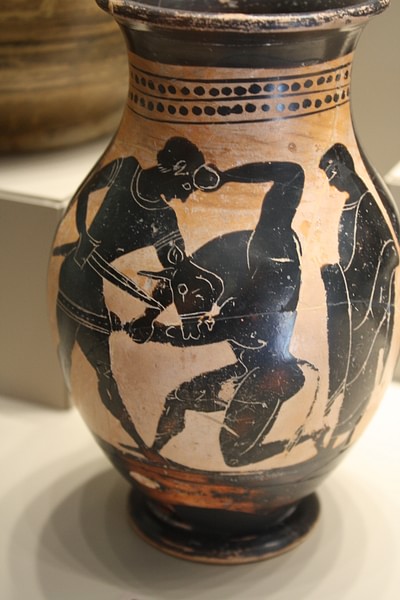

Once on Crete, Theseus attracted the attention of Minos' daughter Ariadne who fell in love with him and secretly gave him a sword and a ball of twine. She told him to attach the thread to the opening of the labyrinth as soon as he was inside and, after he had killed the Minotaur, he would then be able to follow it back to freedom. Theseus kills the monster, saves the youths who were sent with him, and escapes from Crete with Ariadne but abandons her on the island of Naxos on his way home. In his haste to reach Athens afterwards, he forgets to change the sails on the tribute ship from black to white and Aegeus, seeing the black sails returning, flings himself into the sea and dies; Theseus then succeeds him.

The Labyrinth as Symbol of Change

Aside from its purpose as an origin myth – in that the Aegean Sea comes to be so-named for King Aegeus after his death – the story focuses on the coming-of-age of the prince Theseus and how he ascends to the throne. Theseus is the great hero who rescues his companions and delivers his city from the curse of the Minotaur but he is also deeply flawed in that he betrays the woman responsible for his success willingly and, unwittingly, causes the death of his father by forgetting to change the color of the sails.

The labyrinth in the story serves as the vehicle for Theseus' transformation from a youth to a king. He must enter a maze no one knows how to navigate, slay a monster, and return to the world he knows; he accomplishes this but still retains his youthful flaws until he is changed by the loss of his father and must grow up and assume adult responsibility. The labyrinth presented him with the opportunity to change and grow but, like many people, Theseus resisted that opportunity until change was forced upon him.

The archaeologist Arthur Evans (1851-1941 CE) uncovered what he believed to be the labyrinth at Knossos in his excavations between 1900-1905 CE. Although this claim has been challenged, the fabled labyrinth is still associated with the site of Minos' palace at Knossos and ancient writers reference it as an actual site, not a mythological construct. Evans was certain of his find and explained the mythological aspect of the Minotaur through the Minoan sport of bull jumping (shown in frescoes on the walls of the palace) in which, by grabbing the bull's horns and leaping back over the animal, man and bull appeared to be one creature.

Whether there was a literal labyrinth at Knossos, however, is not as important as the meaning of the labyrinth in the story as a symbol of change and transformation. This same type of symbolism is also seen elsewhere and, notably, in the most famous labyrinth of antiquity: that of Amenemhet III (c. 1860-1815 BCE) of Egypt.

The Labyrinth at Hawara

The labyrinth at Hawara was so impressive that, according to Herodotus, it rivaled any of the wonders of the ancient world. Scholar Miroslav Verner notes that Amenemhet III's labyrinthine complex was “mentioned by ancient travelers” and continues:

Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus, Strabo, and Pliny all refer to it. According to Diodorus, Daedalus was so impressed by this monument during his journey through Egypt that he decided to build a labyrinth for Minos in Crete on the same model. (430)

The labyrinth was an Egyptian temple precinct of a pyramid complex comprising multiple courts built at Hawara by Amenemhet III of the 12th Dynasty during the period of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE). This labyrinth was a mortuary complex grander and more intricate than any other constructed up to that time. The monumental structure is described by Herodotus:

I saw it myself and it is indeed a wonder past words… It has twelve roofed courts with doors facing one another, six to the north and six to the south and in a continuous line. There are double sets of chambers in it, some underground and some above, and their number is 3,000…The passages through the rooms and the winding goings-in and out through the courts, in their extreme complication, caused us countless marvelings as we went through, from the court into the rooms, and from the rooms into the pillared corridors, and then from these corridors into other rooms again, and from the rooms into other courts afterwards. The roof of the whole is stone, as the walls are, and the walls are full of engraved figures, and each court is set round with pillars of white stone, very exactly fitted. At the corner where the labyrinth ends there is, nearby, a pyramid 240 feet high and engraved with great animals. The road to this is made underground. (Histories, II.148)

Strabo describes the labyrinth as “a great palace composed of many palaces” and praised it as “comparable to the pyramids” in grandeur (Geography, XVII.I.37-38). Diodorus notes how, “in the carvings and, indeed, in all the workmanship they left nothing wherein succeeding rulers could excel them” (Histories, I.66) and Pliny states:

We must mention also the labyrinths…there is no doubt that Daedalus adopted it as the model for the labyrinth built by him in Crete, but that he reproduced only a hundredth part of it containing passages that wind, advance and retreat in a bewilderingly intricate manner. It is not just a narrow strip of ground comprising many miles of 'walks' or 'rides,' such as we see exemplified in our tessellated floors or in the ceremonial game played by our boys, but doors are let into the walls at frequent intervals to suggest deceptively the way ahead and to force the visitor to go back upon the very same tracks that he has already followed in his wanderings. (Natural History, XXXVI.19)

It is believed that the labyrinth at Hawara, like any of the temple complexes in Egypt, mirrored the afterlife. There were 42 halls throughout the structure which Strabo associates with the number of nomes (provinces) of Egypt but which also correspond to the Forty-Two Judges who preside over the fate of one's soul, along with the gods Osiris, Thoth, Anubis, and Ma'at, at the final judgment in the Hall of Truth. The labyrinth, then, could have been constructed to lead one through a confusing maze – much like the landscape of the afterlife described in the Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, and the Egyptian Book of the Dead – to lead one toward an enlightened state.

This impressive complex fell into decay at some unknown point and was dismantled; the parts were then used in other building projects. So great was the site as a source of building materials that a small town grew up around the ruins. Nothing remains of this great architectural wonder today save the ravaged pyramid of Amenemhet III at Hawara by the oasis of Faiyum. Verner writes, “because of the early destruction of the complex, the original plan of the labyrinth cannot be precisely reconstructed” but notes how the archaeologist Flinders Petrie was the first to enter it in 1889 CE and concluded it was the same structure known as The Labyrinth in antiquity (428).

Scholar Richard H. Wilkinson notes that “it was one of the greatest tourist attractions of Egypt in the Graeco-Roman Period” and that the complex “represented an impressive elaboration of the established temple plan” (134). As temples were purposefully built as transformative sites, the labyrinth-as-symbol-of-transformation motif is as evident here as in the later story of the one designed by Daedalus.

Labyrinths & Their Meanings

There have been many other labyrinths around the world since ancient times from the structure built in Italy as part of the tomb of the Etruscan king Lars Porsena (c. 580 BCE) to those of the island of Bolshoi Zayatsky (c. 500 BCE) in modern-day Russia. Celtic labyrinths are thought to have once been part of the mortuary rituals of Britain, Ireland, and Scotland and scholar Rodney Castleden notes:

Labyrinths constantly reappear in different forms at different stages in the evolution of Celtic culture and some of them are earlier than the Minoan labyrinths. The labyrinth as an idea is closely related to the knot: the line that winds all around a design. The difference is that, in a knotwork design, the line has no beginning and no end while, in a labyrinth, there is usually a starting point and a goal. Both symbolize journeys. This might be a particular journey or adventure or the overall journey of life itself. Labyrinths therefore form a visual counterpart to the epic folk-tale which often consists of a long and convoluted journey with episodes that repeat and double back on themselves. They may symbolize a journey of self-discovery too, a journey in to the center of the self and out again and, in this way, the ancient symbol emerges as a Jungian archetype: a tool for self-exploration and healing. (439-440)

This is certainly evident in the mandalas of Tantric literature from India and, most notably, in the Rigveda (c. 1500 BCE) in which the various books progress along the same lines as a labyrinth where one travels a spiritual path alone to eventually merge one's inner journey with the outer world. Carl Jung (1875-1961 CE) saw the labyrinth as a symbol of this reconciliation between the inner self and the external world. Scholar Mary Addenbrooke writes:

[Jung] describes the effect of being “gloriously, triumphantly drunk. There was no longer any inside or outside, no longer an 'I' and the 'others', No. 1 and No. 2 were no more (he is referring to his sense of having two dissimilar personalities within him); “caution and timidity were gone and the earth and sky, the universe and everything in it that creeps and flies, revolves, rises, or falls, had all become one.” (1)

Jung discusses the journey through the labyrinth in his Stages of Life:

When we must deal with problems, we instinctively resist trying the way that leads through obscurity and darkness. We wish to hear only of unequivocal results, and completely forget that these results can only be brought about when we have ventured into and emerged again from the darkness. But to penetrate the darkness we must summon all the powers of enlightenment that consciousness can offer... The serious problems in life are never fully solved. If ever they should appear to be so it is a sure sign that something has been lost. The meaning and purpose of a problem seem to lie not in its solution but in our working at it incessantly. This alone preserves us from stultification and petrifaction. (11)

The people of the ancient world seem to have understood this concept long before Jung articulated it so eloquently. The labyrinth, finally, is the journey of the self to wholeness. Although the ancient Egyptians or Greeks may not have phrased it this way, their architecture and myths point to the same conclusions Jung and other later psychologists have come to: that it is in working one's way through the labyrinth of one's present circumstances that one comes to realize one's purpose and a final meaning for existence.