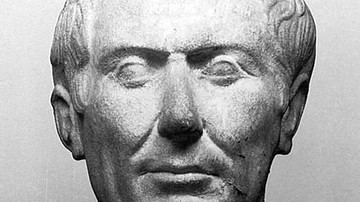

Marcus Junius Brutus (85-42 BCE) was a Roman politician and a leading figure in the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE. Although he was granted amnesty after the Ides of March, a new civil war soon broke out. Brutus committed suicide after he had been defeated by the forces of Mark Antony and Octavian at the Battle of Philippi 42 BCE.

Family

Descended from a prominent Roman family whose ancestor was acclaimed for driving the last king out of the city, Marcus Junius Brutus was born around 85 BCE in Rome. Although unanswered questions abound concerning the true identity of his father, he believed it to be the Roman commander Marcus Junius Brutus. The elder Brutus surrendered to Pompey the Great at the Battle of Mutina in 77 BCE and, although promised safe conduct, was executed. His mother was the outspoken Servilia, step-sister of the prominent orator and statesman Cato the Younger (95-46 BCE). Although adopted by his uncle, the patrician Quintus Servilius Caepio, he was raised by Cato and educated in both oratory and philosophy. He also accompanied Cato to Cyprus in 58 BCE. In his Lives, the historian Plutarch (c. 45/50 to c. 120/125 CE) wrote that Brutus was proficient in all facets of Greek philosophy with a particular fondness for the Platonists. Barry Strauss, in his The Death of Caesar, wrote that his study of philosophy had "added depth and garnered respect. It allowed him to tap into time-honored ideals" (77).

Political Career

Brutus began his climb on the cursus honorum, the sequence of Roman government offices, in 53 BCE when he became a quaestor and was assigned to Cilicia with Claudius Pulcher, whose daughter, Claudia, he would marry. With the influence of Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE), he would become a praetor in 44 BCE, and he was designated for a consulship in 41 BCE — the latter would, of course, never come to be. In 54 BCE, he penned a pamphlet attacking the consul Pompey, who, many believed, sought a dictatorship, but these allegations were unfounded and dismissed by Pompey. In 52 BCE, he and Marcus Tullius Cicero used their oratory skills to unsuccessfully defend Annius Milo for murder; he was ultimately found guilty and exiled.

Although Brutus had long maintained a deep contempt for Pompey for killing his father, the two surprisingly reconciled their differences when Pompey abandoned his support of Caesar and joined the Republican cause – a cause Brutus had already joined in 49 BCE. When Pompey took up arms against Caesar, two factions emerged: one supporting Caesar and the other supporting Pompey. Many expected Brutus to follow Caesar, but he joined Pompey instead and fought alongside him. Referring to Brutus' decision, Plutarch wrote that he had put aside his own personal feelings, and "judging Pompey's to be the better cause, took part with him; though formerly he used not so much as to salute or take any notice of Pompey … but now, looking upon him as the general of his country, he placed himself under his command" (1085).

In the aftermath of the Battle of Pharsalus in Greece in 48 BCE, where Pompey suffered a disastrous defeat, the defeated general went to Egypt, where he was stabbed to death, and Brutus appealed to Caesar for forgiveness. He received clemency for himself – probably at the urging of Servilia – and his friend (and fellow future conspirator) Cassius. It was no secret that Caesar and Servilia had had an affair, and this relationship was evident in Caesar's treatment of Brutus. When Caesar left Rome to engage Cato and the Republicans in Africa, he showed his confidence in Brutus by naming him the governor of Cisalpine Gaul. While admittedly no general and with little political experience, he deferred to Roman constitutional norms. Plutarch maintained that he was well-received by the people there. The people of Mediolanum even erected a statue of him.

Friendship with Ceasar's Enemies

While Caesar was in Africa battling Cato, Brutus developed a strong relationship with the Roman orator Cicero. He divorced his wife Claudia and married Cicero's daughter Portia, the widow of the conservative and former consul Calpurnius Bibulus, an archenemy of Caesar. Cicero and Brutus both wrote eulogies for the fallen Cato, who had committed suicide rather than surrender to Caesar – Caesar was not amused. Brutus agreed with Cato's belief that freedom required sharing power, something that would come in direct opposition to Caesar's role as a dictator. However, despite this, he still saw no contradiction between his allegiance to Caesar and remaining loyal to the memory of Cato and his principles. Of course, this attitude would soon change. Slowly, Brutus began to seriously question his loyalty to Caesar.

With Caesar's defeat of both the king of Pontus in the East and his success against Cato and Pompey, the Roman commander had entered the eternal city in a Roman triumph. Hailed as a hero, he was awarded the title of liberator, named the father of his country, and made consul for ten years. With the overwhelming support of the people and the Roman Senate, Caesar initiated a number of reforms. Although praised at first for both his military skills and leadership, he gradually began to create fear in the minds of many of those inside and outside the Senate. Many came to believe he was becoming more of a divine figure than a ruler, gradually inching away from the traditional values of the Roman Republic that they had hoped he would restore. Even the Roman people believed they no longer had a voice as their beloved Rome was quickly coming under the control of a would-be tyrant, and so the seeds of a conspiracy were born. Suetonius wrote:

Several groups, each consisting of two or three malcontents now united in a general conspiracy. Even the people had come to disapprove of how things were going and no longer hid their disgust at Caesar's tyrannical rule but openly demanded champions to protect their ancient liberties. (37)

In his book Julius Caesar, Philip Freeman claimed there were three types of people who wanted Caesar dead:

- his old enemies, former allies of Pompey

- friends who respected him as a military leader but resented his policy of reconciliation instead of initiating a purge

- the idealists who believed in the old traditional Republican values

As the idea of a conspiracy slowly emerged, it became apparent that Brutus was vital to any scheme against Caesar. His personality made him the ideal candidate to lead. Barry Strauss said that Brutus was not only intelligent and forceful but also "proud, talented, sober, high-minded and a little vain" (15). He was all things to all people. The conspirators wanted "the reputation and authority of a man ... to give as it were the first religion sanction, and by his presence ... to justify the undertaking" (Plutarch, 1088).

Time was becoming a major concern, for the conspirators had to act quickly with Caesar preparing to embark on a three-year Parthian campaign to avenge the death of Marcus Licinius Crassus (115-53 BCE), who had been defeated and killed in the Battle of Carrhae, 53 BCE. Caesar planned to leave for Parthia on 18 March 44 BCE. With time being of the essence, Brutus was under pressure to join the plot.

Brutus Joins the Conspiracy

His old friend Cassius was instrumental in soliciting other people to join the plot, but he also recognized that, according to Plutarch, they did not need just hands but a man of authority. Strauss wrote that, "If a man of his pedigree and principle calls Caesar a tyrant then people would believe him" (78). Self-interest would eventually move Brutus away from Caesar. According to Plutarch, support came from an unsuspected source. His wife, Portia, unknowingly helped to convince him to join the conspirators. Although not aware of the plot, she recognized that serious troubles plagued her husband. One late evening, as they spoke, "he lifted up his hands to the heavens, and begged the assistance of the gods in his enterprise" (Plutarch, 1090). Brutus knew what had to be done.

The four principal leaders of the plot were Gaius Trebonius, who had organized the siege of Massilia and fought with Caesar in Spain; Decimus Brutus, who was one of Caesar's former commanders; Gaius Cassius Longinus, who had served under Crassus and Pompey; and lastly, Marcus Junius Brutus. With the leadership established, they had to decide where to attack: on a highway, in a public place, while he was walking home, or maybe at a gladiatorial game. Finally, it was decided to attack him during the session of the Senate to be held at the Theater of Pompey (the regular Senate building was being renovated). The date would be 15 March 44 BCE — better known to history as the Ides of March, three days before he was scheduled to leave for the East. If he left on his campaign, he would become untouchable – away from Rome and surrounded by his loyal army. The attackers had even chosen their weapon, a double-edged dagger, or pugio, of about 20 centimeters (8 in) long.

The Assassination

On the morning of the assassination, Caesar's wife, Calpurnia, begged him not to go; she had had a terrible nightmare where she saw him die in her arms, but Caesar put little faith in omens. Suetonius (69 to 130/140 CE) wrote:

"... warnings and a touch of ill-health, made him hesitate for some time whether to go ahead with his plans or whether to postpone the meeting. ... Some of his friends suspected that, having no desire to live much longer because of his failing health, he had taken no precaution against the conspiring and neglected the omens and warnings of well-wishers. (41).

Soon, Decimus Brutus arrived at his home and convinced him not to disappoint the senators who expected him. As he was carried on his litter to the Theater of Pompey, he was surrounded by a throng of people. As he was about to enter the hall, he received last-minute warnings. Artemidorus passed him a scroll alerting him of a plot, but Caesar simply stuffed it into his toga, and the soothsayer Spurninna attempted to warn him, but she, too, was dismissed. Mark Antony (83-30 BCE) was there, but he was stopped at the hall entrance by Trebonius. The conspirators had planned to assassinate Antony, too, but Brutus had nixed the idea.

As Caesar took his seat, there were 200 senators in attendance that day along with ten tribunes, slaves, and secretaries. Cimber approached the unsuspecting Caesar and handed him a petition on behalf of his exiled brother. Cimber grabbed at Caesar's toga and pulled it back. It was a signal for the others to attack. Casca dealt the first blow with his knife; Caesar immediately tried to defend himself by raising his hands to cover his face. The remaining conspirators surrounded Caesar. Lastly, Brutus approached and drew his dagger. Ironically Caesar died at the foot of the statue of Pompey.

Philippi

The conspirators had made little, if any, attempt to prepare for after the assassination. Brutus simply wanted to return power to the Senate and the people, but with no obvious leadership and the city on the brink of chaos, that now seemed impossible. The city was in shock; the people were growing hostile. There were some who falsely believed that the whole Senate had joined in on the assassination. To Brutus and the others, it had not been murder but only the killing of a tyrant. Now calling themselves liberators, Brutus and the others openly walked the streets of Rome to Capitoline Hill and the Roman Forum, daggers exposed. They made preparations on the Hill to protect themselves against all possibilities.

The next few days brought public meetings in an attempt to gauge public opinion and private meetings at Antony's house. The liberators had mixed feelings about Antony and his objectives. Brutus had saved him from being assassinated alongside Caesar, but now he was the lone chance for a compromise or amnesty. Later, he would become their worst enemy. On 17 March, a compromise was reached by the Roman Senate at the urging of both Mark Antony and, surprisingly, Cicero. The staunch republican Cicero pointed out to the Senate that the people were living in fear, and a compromise, leaving the assassins unpunished and Caesar's laws in force, was necessary. The compromise did exactly that, but in reality, peace was impossible to maintain.

On 20 March 44 BCE, Caesar's body was to be burned on a pyre constructed at the Field of Mars near his family tomb, but the body was snatched and taken to the Temple of Jupiter and burned there. Suetonius wrote: "As soon as the funeral was over, the people snatching brands from the pyre ran to Brutus and Cassius and were repelled with difficulty" (41). With Caesar's old veterans arriving in town, Antony took advantage and claimed leadership.

Realizing amnesty was no longer possible, Brutus and Cassius fled the city. However, a challenger to Antony appeared: the adopted son and heir of Julius Caesar, Octavian. Antony and Octavian would initially put aside their differences, and together with Marcus Lepidus, they formed the Second Triumvirate. Strauss wrote that "Blood money and real estate were the first order of business for the triumvirs" (213). With little alternative, Brutus and Cassius joined forces, and in October 42 BCE, they met Antony at the Battle of Phillipi. Accepting defeat and not wanting to be captured, they both committed suicide.

At Antony's orders, Brutus' ashes were taken to his mother, Servilia, while his head was placed at the foot of a statue of Caesar. Although most give credit for the defeat to Antony, Suetonius cites Octavian, the future Augustus: "Augustus defeated Brutus and Cassius at Philippi, though ill health at the time. ... he showed no clemency to his beaten enemies, but sent Brutus' head to Rome for throwing at the feet of Caesar's statue..." (48). Regarding the other liberators, Suetonius wrote, "All were condemned to death and all met it in different ways – some in shipwreck, some in battle, some using the very daggers with which they had treacherously murdered Caesar to take their own lives" (42).

In medieval literature, Brutus and Cassius were placed in the ninth and lowest level, Cocytus, of Dante's Inferno, a place reserved for those guilty of treachery and betrayal towards their country. Caesar, on the other hand, spent his eternity with the virtuous pagans. According to Strauss, the tragedy of the Ides of March was that rather than initiating a return to the Republic, it brought about a new civil war with a vengeance.