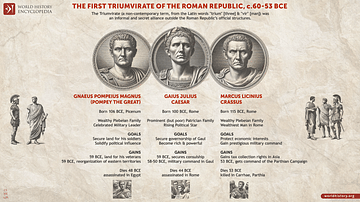

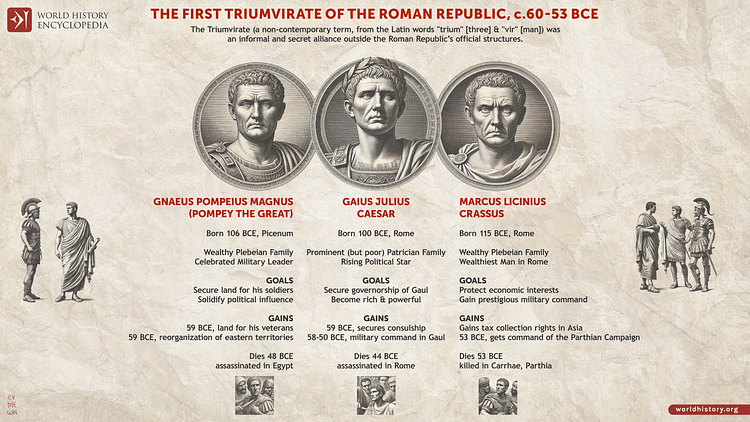

Marcus Licinius Crassus (115-53 BCE) was perhaps the richest man in Roman history and in his eventful life he experienced both great successes and severe disappointments. His vast wealth and sharp political skills brought him two consulships and the kind of influence enjoyed only by a true heavyweight of Roman politics. A mentor to Julius Caesar in his early career, Crassus would rise to the very top of state affairs but his long search for a military triumph to match his great rival Pompey would, ultimately, bring about his downfall.

Early Success

Crassus was the son of Publius Licinius Crassus, who was consul in 97 BCE and a commander in Iberia, even gaining a triumph for his victories in Lusitania in 93 BCE. In 87 BCE, on the losing side against the forces of Gaius Marius and Cornelius Cinna, he committed suicide and the young Crassus fled to Spain. Following Cinna's death, Crassus sided with Sulla against Marius, and, as one of his most able commanders, helped him gain control of Italy. Following victory, Crassus now also seized the opportunity to vastly increase his personal wealth from the confiscation of the assets of declared enemies of the state (proscription) which included property, riches and a huge number of slaves.

In private life, Crassus was married to Tertulla, and he had two sons, one of whom shared his name and the other - Publius Licinius Crassus - fought with him in Parthia. Marcus Licinius Crassus the younger enjoyed some military success, notably achieving the highest Roman military honour of killing an enemy king.

Crassus senior was embroiled in a scandal when he was accused of getting too familiar with a Vestal virgin, one Licinia. Crassus was acquitted, though, on the grounds that really he had only been interested in getting a lower property price for one of his development schemes and, as Plutarch put it, his reputation for respectability was saved by his reputation for avarice. He was not known as a mean man, rather, he was known as generous to his friends and his popularity with the people not only came from his offers of free parties and grain but also his polite manner and lack of snobbery. Crassus was also a good orator, no doubt a skill he honed via his many court cases and helped by his love of philosophy. Plutarch mentions that even Cicero would think twice before engaging in legal argument with Crassus.

The Spartacus Rebellion

The slave rebellion of the early 70s BCE led by Spartacus, the Thracian gladiator, would present Crassus, made praetor in 73 BCE, with an opportunity to flex his military muscle and gain further prestige with the Roman people. The slave army, numbering between 70,000 and 120,000, was a serious threat and had already defeated two separate Roman armies and two consuls. Now they were ravaging the southern Italian countryside and it was Crassus who was entrusted with finally removing this thorn from Rome's heel. In 71 BCE he unsuccessfully attempted to corner Spartacus in Bruttium where his lieutenant Mummius rashly disregarded Crassus' orders and openly attacked the slave army with two legions, was routed and even forced to abandon arms. In response to this setback Crassus employed the ancient punishment of decimation on a 500-man section of Mummius' force, where one in ten legionaries was killed by their fellows in full view of the whole army.

With eight legions at his disposal, Crassus cornered Spartacus at Lucania, finally defeated the slave army, and crucified 6,000 of the survivors along the Appian Way. However, some of the prestige for suppressing the slave rebellion was also claimed by Crassus' great rival Pompey who, returning from Spain, mopped up those slaves who had escaped the battle. Further, back in Rome, it was Pompey who was given the honour of a triumph (in recognition of his other military successes) whilst Crassus was given the lesser ovation. Splashing his cash, though, Crassus won favour by hosting a long round of lavish celebratory feasts for the people of Rome and in response to Pompey's popular title of 'Great', Crassus would ask dismissively 'Why, how big is he?'

Political Manoeuvres - The Triumvirate

Settling their differences following the Spartacus episode, Pompey and Crassus pressurised the Senate and were made consuls in 70 BCE, an opportunity Crassus made full use of to further increase his wealth and influence. The pair overhauled Rome's political structure, overturning Sulla's constitution and expelling 64 senators. Politically, though, Crassus again lost ground to Pompey following the latter's string of military victories, notably his spectacular eradication of the Mediterranean pirates in just three months and the swift defeat of Mithridates VI in the East.

Made censor in 65 BCE, Crassus' two most significant policies of granting citizenship to the Transpadanes (in the part of Cisalpine Gaul north of the river Po) and annexing Egypt both failed and he was forced to resign from the position. Also, his backing of Catiline failed to secure this dangerous and unscrupulous schemer the consulship of 65 or 64 BCE and the Senate, instead, went for the more conservative Cicero. According to Suetonius in his biography of Caesar and a lost work by Cicero (quoted in secondary sources), Crassus had actually planned in 65 BCE, in collusion with Caesar, Publius Sulla and Lucius Autronius, to make himself dictator by purging the Senate of opposition but the conspirators inexplicably lost their nerve at the last moment. The story is rejected as a fiction by most modern scholars.

Crassus continued to pull strings behind the political scenes, largely functioning as a patron of younger men such as Julius Caesar, whose debts Crassus guaranteed in 62 BCE. Caesar also persuaded Crassus to settle his differences with Pompey so that both would support Caesar's bid to become consul, which he achieved in 59 BCE. In return, Caesar passed a law which cancelled one-third of the money owed by public contractors (publicani) in Asia, a move which further increased Crassus' now legendary personal fortune. According to Plutarch, Crassus had accumulated the vast sum of 7,100 talents, had extensive real estate interests, owned silver mines, possessed a huge number of slaves, and, of course, he was able to fund his own army.

The three men now formed an open alliance known as the First Triumvirate but it was at times an uneasy one. When Caesar left for Gaul, Crassus found a new protege in P. Clodius Pulcher but he turned out to be a dangerous and unreliable ally. In 56 BCE Crassus did warn Caesar that Cicero planned to politically isolate him from Crassus and Pompey. To reinforce their alliance, Crassus met Caesar at Ravenna and then all three met together at Lucca. The plan was for Crassus and Pompey to be made consuls once more with the former given a 5-year command in Syria and the latter given the same position in Spain. In turn, they would both call for a renewal of Caesar's command allowing him another 5-year term as governor in Gaul and the consequent opportunity to expand his army. All going according to plan, Crassus left for Syria in 55 BCE where he was set on a lucrative invasion of Parthia.

Disaster in Parthia

Crassus' initial stay in Syria proved successful as he extorted enormous riches from the local population and won several military victories in 54 BCE. Crossing the Euphrates in 53 BCE, and accompanied by his son P. Licinius Crassus as a cavalry commander, the elder Crassus was confident of more success. However, already deserted by the Armenian king Artavasdes II and having lost his son in an overly-aggressive earlier attack, Crassus himself was defeated near Carrhae. Without sufficient cavalry and logistical support, hampered by the campaign's lack of planning in the harsh desert terrain, and suffering a little local treachery, the legions were unable to adequately face the 10,000 skilled mounted archers of Orodes II, the Parthian king. Consequently, the Romans were encircled, trapped and forced to surrender arms and their Eagle standards (a point which would rankle with Rome until their retrieval by Augustus). According to legend, Crassus was captured alive and killed by having molten gold poured down his throat, symbolic of his unquenchable thirst for wealth.

With the removal of Crassus from the political game to control Rome, Pompey and Caesar were left to fight out a bloody civil war which would lay the foundations for a complete overhaul of Roman politics and, ultimately, open the doors to dictatorship and the Imperial age.

Conclusion

Crassus was one of the old-school politicians of Republican Rome. Hugely successful in his early years and acquiring vast wealth, he was, perhaps, left behind the times when Rome edged towards the new era of Imperial politics and a time when military prowess and might came to count far more than mastery of politics. Unable to match the victories of Pompey and Julius Caesar, Crassus died in his attempt to conquer Parthia, in what was his last and fateful throw of the political dice.