Marguerite de Navarre (l. 1492-1549) was a writer, philosopher, diplomat, and Queen of Navarre, sister of King Francois I (Francis I of France, r. 1515-1547), mother of Jeanne d’Albret (l. 1528-1572) and grandmother of Henry IV of France (l. 1553-1610). She was also a proponent of the Reformation, mediating between Protestants and Catholics in France.

Also known as Margaret of Navarre and Marguerite of Angouleme, she is best known today for her Heptameron (1558) published posthumously and unfinished at her death but regarded as one of the most significant works of the Renaissance. She corresponded with some of the greatest Reformers of her time including Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546), Philip Melanchthon (l.1497-1560), John Calvin (l. 1509-1564), Guillaume Farel (William Farel, l. 1489-1565), and Marie Dentiere (l.c. 1495-1561). Marguerite and Dentiere were friends and she was also close to Anne Boleyn (l. c. 1501-1536) and patronized the work of Leonardo de Vinci (l. 1452-1519) who spent his last years at the chateau she and Francois I provided.

Although she never officially renounced Catholicism, she supported the Protestant Reformation in France, protected Protestant preachers and writers from persecution, and advanced the cause of reform by financing translations of Luther’s and Calvin’s works, as well as other commentaries on scripture and scripture itself, into French. She supported and protected the Reformer Jacques Lefevre d’Etaples (l. c. 1455-c.1536), the first theologian to translate the New Testament into French, and used her influence with her brother to prevent his arrest and the destruction of his work.

She was an advocate for the poor and for unwed mothers, establishing hospitals, almshouses, and orphanages, while also tending to her responsibilities at court and writing almost constantly. Her letters, poems (especially her Mirror of the Sinful Soul), plays, and Heptameron continue to be widely read in the present day and she is remembered as a great Renaissance woman who fully embodied the better aspects of her age.

Education & First Marriage

Marguerite was born 11 April 1492 to Charles, Count of Angouleme (l. 1459-1496), a descendent of Charles V of France (r. 1364-1380), and the noblewoman Louise of Savoy (l. 1476-1531). Her parents were both well-educated, valued books, and kept a large library. Although educating girls was considered a pointless waste of time, Marguerite was tutored by scholars from a young age, even after their second child, Francois, was born in 1494 as it was thought the sister of a future king should be able to converse on many different topics. Scholar Marcel Tetel comments:

Marguerite of Angouleme could not have come from a more privileged background. Since neither of the last two kings of France, Charles VIII (died in 1498) and Louis XII (died in 1515), left any male heir, the Angouleme branch of the Valois were to inherit the throne. Marguerite and her brother, the future Francis I, spent their childhood first in Cognac, Angouleme, and then in the Loire Valley in the chateaux of Blois and Amboise. It is in these settings that she learned Latin, Italian, and Spanish [and, later, German and Hebrew], studied classical philosophy, and the scriptures. (Wilson, 99)

Her father was struck with a serious illness in the late winter of 1495 and died in January 1496, leaving her mother a widow at the age of 19. Louise moved the family to the court of Louis XII (r. 1498-1515), her husband’s cousin, and advanced both of her children there, supervising their education, and ingratiating Francois to the king. As she had done earlier, Louise invited the finest scholars to tutor her children and Marguerite grew up reading the Bible, Plato, Cicero, Virgil and, later, Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio. She was especially influenced by Plotinus as a philosophical complement to Christianity.

Louis XII arranged the marriages of both children – Francois to his daughter Claude of France (l. 1499-1524) in 1514 and Marguerite to Charles IV, Duke of Alençon (l. 1489-1525) in 1509. King Henry VII of England (r. 1485-1509) had asked Louis XII for Marguerite as wife for his second son (the future Henry VIII of England, r. 1509-1547) but Louis XII wanted access to the lands of Charles IV and so refused (thereby unwittingly sparing Marguerite from becoming Henry VIII’s first wife). The match was not a happy one and Marguerite is said to have cried throughout the wedding service. Charles IV was illiterate, had no interest in books, and was primarily concerned with hunting. Marguerite had books imported to her new home at the castle in Alençon and also invited musicians, poets, and scholars to regular dinners.

Marguerite was not satisfied with only conversing about religious and philosophical concepts, however, but worked to apply them practically. She encouraged her fellow noblewomen to contribute to building hospitals, orphanages, and almshouses in Alençon and drew up regulations for the institutions mandating regular meals of healthy foods, daily hygiene, and respect for the persons – especially women – who sought shelter at them. Unmarried pregnant women were provided with shelter, food, and support before and after giving birth and any act of molestation or rape was severely punished.

Francois I became king in 1515 and Marguerite asked him to establish a hospital in Paris for orphans to separate them from the adult population which often preyed upon them in the Parisian almshouses. As at Alençon, she sent representatives to Paris to make sure her regulations were implemented and followed and there were no instances of abuse.

By 1521, Martin Luther’s message of reform was circulating in France and Marguerite sought spiritual counsel from Jacques Lefevre d’Etaples, a highly respected theologian sympathetic to reform. He sent her to Guillaume Briconnet, Bishop of Meaux, also engaged in reforming the Church from within, who became her spiritual mentor for the next three years. During this time she encouraged evangelical writers’ works and began to write religious poetry and contemplative pieces.

Deaths & Ransom

In 1524, Francois I’s wife Claude died, and Marguerite took over the care of her children who included Madeleine of Valois (1520-1537) and Margaret of Valois (l. 1523-1574). In August, all six children were struck with measles and the eldest, Princess Charlotte, who was her favorite, died. Claude’s death, followed by Charlotte’s, inspired Marguerite to compose her Dialogue in the Form of a Nocturnal Vision in which Charlotte’s spirit comes to comfort Marguerite in her grief, reminding her of the promise of heaven, and rebuking her for weeping when death is only a transition from the mortal world to eternal life. Marguerite-as-Narrator rejects this vision because the pain of loss is too great to bear, she feels as though she died herself, and asks to be taken where Charlotte is. Charlotte replies that she must wait on God to call her home in His own time and then ascends into the light, leaving the narrator alone but comforted in the hope of God’s mercy. Although the poem emphasizes the importance of faith, it is a deeply personal expression of the pain of grief, still resonant in the present day.

That same year, Francois I left Paris to wage war in Italy against Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire in the continuing Italian Wars (1494-1559), supported by his nobles including Marguerite’s husband and Henry d’Albret (the future Henry II of Navarre, l. 1503-1555). Francois I was defeated at the Battle of Pavia 24 February 1525 and was taken prisoner along with some others, including Henry d’Albret, while Charles IV escaped and made his way back to France. Marguerite tended to her husband’s wounds and the illness he had returned with, even though her mother and other nobles rebuked her as Charles IV was thought to have been responsible for Francois I’s capture, until he died in April on her 33rd birthday.

Marguerite now took on the responsibility of negotiating the release of her brother and the other captives held in Spain for ransom. She traveled to Madrid in October 1525 to meet with Charles V under a promise of safe conduct, but negotiations dragged on and Francois I, fearing Charles V was purposefully keeping her there until the time of her safe conduct ran out and she could also be held hostage, told her to leave. Back in France, she continued negotiations, finally resulting in the Treaty of Madrid in January 1526 and the release of the captives, though her nephews Francois and Henry had to be exchanged as hostages for their father.

Queen of Navarre & Reformation

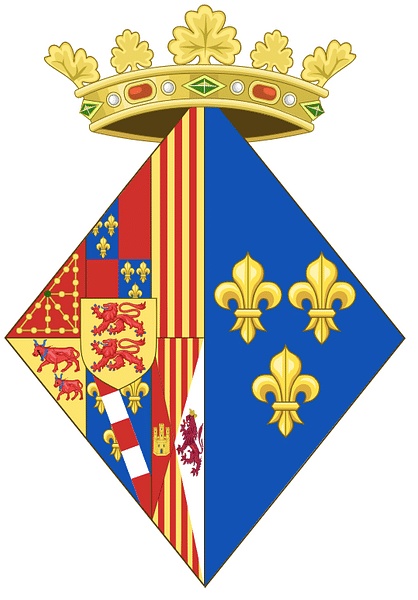

While Francois I had been held in Spain, the Catholic clergy of France had moved against evangelical theologians including Jacque Lefevre d’Etaples whose works were suppressed. Once Francois I returned, he stopped these persecutions at Marguerite’s request, even though he was not sympathetic to the cause, and allowed d’Etaples to continue his work. Francois I then either encouraged or arranged his sister’s marriage to Henry II of Navarre. Henry II had escaped from Spain before the negotiations were concluded and may have assisted Marguerite in the later stages of talks. The two were married in December 1526 and she became Queen of Navarre.

In Navarre, she pursued the same course she had at Alençon in helping the poor while also protecting evangelical priests, writers, and activists. Her daughter, Jeanne d’Albret, was born in 1528 and, in 1529, Marguerite served as a hostage during negotiations to free her nephews from Charles V. Her son, Jean, was born in 1530 but did not survive the year, and her mother died in 1531. Marguerite turned to poetry to express her grief and feelings of separation from God, writing one of her best-known works, Mirror of the Sinful Soul (1531), a monologue directed to Christ in which the narrator relates her own state of misery and sin for readers to reflect on regarding their own.

After her mother’s death, Marguerite spent more time in Paris at her brother’s court where she continued her support of evangelical teachings and publications and attempts at reconciling Catholics and evangelical Protestants. She published Mirror of the Sinful Soul in an edition including translations of Psalms by a reformist writer which led to her poem, and the volume as a whole, being condemned. Francois I had the condemnation lifted and protected his sister and the contributors but the Faculty of Theology of the Sorbonne were able to convict the printer of dissemination of heretical works and he was later hanged.

Francois I continued his protection of Marguerite and those she advocated for until the event known as the Affair of the Placards in October 1534 when, between the 17th and 18th, placards denouncing the Catholic Mass and advocating the views of Reformer Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) were posted publicly in Blois, Orleans, Paris, Rouen, and Tours – one of them appearing on the bedroom door of Francois I’s chateaux. Modern-day scholars continue to debate whether this was the work of the Reformer Antoine Marcourt (as traditionally understood) or of Catholic authorities who had tired of Francois I’s lenient policies toward evangelicals and framed Marcourt and others. Whoever was responsible, Francois I reacted by refusing to protect Marguerite’s associates any longer and initiating persecution of Protestants throughout France.

John Calvin fled France at this time, along with many others, stopping at Marguerite’s castle in Navarre before going on to Geneva in 1536. Printing of any kind was curtailed by the king who decreed which sort of works would now be authorized and anyone suspected of taking part in the Affair of the Placards or supporting those involved was arrested and many Protestants burned at the stake. Navarre became a safe haven for Protestants as Henry II supported his wife’s policies of religious tolerance and exchange of ideas, but she no longer exerted the kind of influence over her brother has she had previously.

Influence & Heptameron

At some point, between 1531 and 1536, Marguerite had sent a copy of Mirror of the Sinful Soul to her friend Anne Boleyn in England. Anne had been a lady-in-waiting at the court of Queen Claude and kept up a correspondence with Marguerite after the queen’s death. It is thought that Marguerite influenced reform in England through this correspondence as Anne herself was sympathetic to reform and her daughter Elizabeth (the future Elizabeth I of England, r. 1558-1603), translated the poem into English in 1544, introducing it to an international audience.

Marguerite also inspired one of the best-known works of the Reformation when she wrote to her friend Marie Dentiere in 1539 asking why Calvin and Farel had been expelled from Geneva. Dentiere’s response was her open letter to Marguerite known as Marie Dentiere’s A Very Useful Epistle which advocated for a greater role for women in the Reformation, women’s rights in general, and the banishment of Catholic clergy from France.

She also may have exerted indirect influence on the young reformist scholar Olympia Fulvia Morata (l. 1526-1555) of Ferrara, Italy who was a court companion of Anna d’Este (l. 1531-1607), daughter of Renee of France (l. 1510-1574). Marguerite corresponded with Renee, as she did with many others, and Renee became well-known as an advocate for religious reform. Morata would become one of the greatest classical scholars of her day and is also remembered as a passionate advocate for the Reformation.

Marguerite was also the patron of Francois Rabelais (l. 1483-1553), protecting him and encouraging his publication of Gargantua and Pantagruel, and of her close friend and poet Clement Marot (l. 1496-1544) and the poet Pierre de Ronsard (l. 1524-1585), among many others, including Leonardo da Vinci whose final works were all due to her patronage. She is best known, however, for her Heptameron, her most ambitious work, which was left unfinished at her death.

The Heptameron is a collection of 72 thematically linked and interwoven tales told by five women and five men stranded in an abbey. A flood has washed out the only bridge nearby and it will take ten days to rebuild it. While they wait, they agree to entertain themselves with stories of love and the challenges of romantic relationships. Marguerite envisioned the work as a French Decameron, and she references Giovanni Boccaccio directly in her prologue, which also makes clear the work will include 100 tales. At the time of her death, only 72 had been completed or, were thought to have been; scholars continue to work from the various extant manuscripts and versions published between 1558 and the 19th century to establish an authoritative version of the work as it seems clear Marguerite wrote more than were included in the earliest posthumous publications.

Conclusion

Heptameron, though popular reading from its first appearance, was criticized as vulgar by some and condemned for its depiction of Catholic clergy as rapists and predators. Ultimately, though, it is a religious work which encourages belief in the Neo-Platonic concept (inspired by Plotinus) of a greater and more lasting reality above the world of sense perception and experience. This vision is entwined with the Christian concept of heaven and love of God who, unlike human lovers, remains forever faithful. Tetel comments on the theme and message of the work:

Ultimately, strong and genuine faith offers the only possible solace after one has experienced the vagaries and pitfalls of man/woman relationships. Ideally, one should seek goodness in the other and give one’s goodness to the other – this is called perfect love – but, in practice, flesh and the senses dominate, given the inherent weakness of human beings and the fallen state of humankind. Yet, man/woman relationships are necessary, if not welcome, for they make one realize the transient nature of these relationships and of life, and then pave the way to a higher spiritual comfort. (Wilson, 102)

Marguerite’s other works deal with this same theme, or similar ones, in maintaining the existence of lasting meaning and enduring love in a world of constant change and death. She lost her friend Marot in 1544, ended her correspondence with Calvin in 1545 over his harsh criticism of her and, the same year, lost her favorite nephew, Charles. Her brother died in 1547 and, as before, she turned to poetry to express her grief and faith in an afterlife and a loving God who would return what was lost when all were reunited in heaven.

She died of pleurisy in December 1549 and, unlike many of her contemporary female writers, her works were preserved intact and were first published within ten years of her death. These works, especially Heptameron, found a wider audience in the 19th century and Marguerite’s reputation as a great Renaissance woman has only grown since then. Today she is recognized as one of the most significant figures of her time both for her literary achievements and her contributions toward social reform and freedom of religious expression.