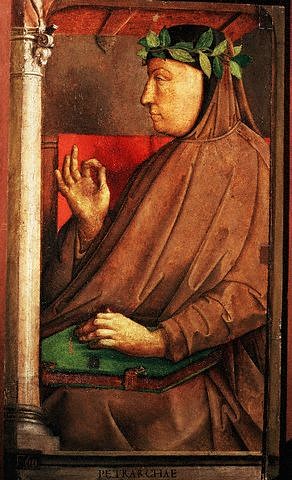

Petrarch (1304-1374 CE), full name Francesco Petrarca, was an Italian scholar and poet who is credited as one of the founders of the Renaissance movement in art, thought, and literature. Petrarch actively searched for 'lost' ancient manuscripts hidden away in forgotten corners of medieval libraries; Cicero (106-43 BCE) was one particular beneficiary of Petrarch's diligence but there were many others besides. He not only found, edited, and collected these ancient works together but also wrote a vast catalogue of his own poems, texts, and letters. Petrarch's most famous work today is his Canzoniere, a collection of love poems written in the vernacular which revolve around an unknown and unobtainable woman called Laura. Through his discoveries, scholarship, and original works, Petrarch spearheaded a revival in ancient ideals and secular intellectual studies which focussed on human affairs rather than religious matters, even if, paradoxically, he himself remained very much interested in Christian studies. Consequently, Petrarch is, in this respect, considered the father of what became known as Renaissance humanism.

Early Life

Petrarch was born in Arezzo, Italy on 20 July 1304 CE to parents who were exiles from the city of Florence. Around 1311 CE the family moved again, this time to Avignon in southern France, home of the now-exiled popes. His father was a notary and so Petrarch, too, studied law, first in Montpellier in France in 1316 CE and then back in Italy in Bologna in 1320 CE. The dry legal studies were not to his taste, though, and Petrarch decided to abandon law following his father's death in 1326 CE to instead focus on his first love: literature. He needed a patron for such activities but struggled to find a lasting one throughout his career. In his early working life, he had to settle for trivial clerk duties until something better came along and so he took minor orders and worked for Cardinal Giovanni Colonna in Avignon until 1337 CE. His required commitment to celibacy did not stop him fathering two illegitimate children, Giovanni in 1337 CE and Francesca in 1343 CE.

Public Life

In his search for more meaningful employment, Petrarch shifted about various courts of French and Italian city-states, notably those at Naples, Padua, and Milan. He also travelled for scholarly purposes, visiting men of learning and monastery libraries in France, Flanders, and the Rhineland. Throughout, he maintained a property in the hills of Vaucluse near Avignon, which he returned to sporadically as he deplored what he saw as the corruption and duplicity of court life in the cities which gave him employment. This nomadic lifestyle is reflected in such works as the 1346 CE De Vita Solitaria (On the Solitary Life) and the 1347 CE De Otio Religioso (On Holy Retreat).

Nevertheless, Petrarch did try and involve himself in practical politics, albeit with indifferent results. Unable to promote the reforms he hoped would make politics and rulers less hypocritical and corrupt, his greatest disappointment was seeing the popular leader Cola di Rienzo (1313-1354 CE) fail to revive the government of Rome as capital of a 'sacred Italy' in 1347 CE.

The high point of Petrarch's public career was perhaps his coronation as Poet Laureate in Rome on 8 April 1341 CE. He was by then internationally famous as a poet and scholar and was the first to receive this award, which was revived from antiquity. Petrarch had long lobbied the Pope to have the title, and it symbolised for him the possibility that poets and scholars could lead Italy and Europe back to the glory days of the Pax Romana of the Roman Empire. This would be a rebirth, a renaissance. From then on, he concentrated on literature, both studying the past and creating new works for the future.

Retreat into Scholarship

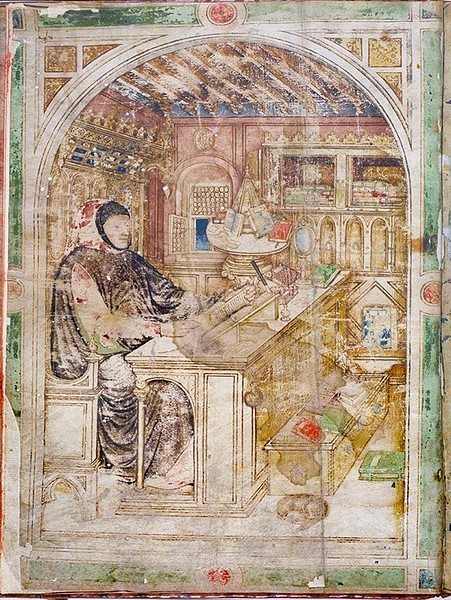

Petrarch seems to have adopted Cicero's approach to life, the Roman scholar whose works he rediscovered as he searched Europe's libraries for ancient texts. This approach was otium cum dignitate or 'leisure spent properly', that is, a man of learning should find the right balance between a fully active public life and a reclusive private life devoted to study. Indeed, never abandoning his religious beliefs despite his interest in the pagan past, Petrarch was, too, a keen student of the works of Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430 CE), whom he thought more significant than Aristotle (384-322 BCE), a figure who then greatly preoccupied scholars. Petrarch considered the medieval church as a source of continuity from antiquity through the centuries to his own times, but he was against the scholasticism which had bogged down thinkers with endless circular arguments on dogma. He continued to search out the works of Latin and Greek authors. Even if he could not read Greek himself (although he tried to learn), he accumulated manuscripts in that language such as the Iliad by Homer (c. 750 BCE). He most famously rediscovered copies of letters and speeches by the Roman statesman and author Cicero; in 1333 CE in Liège, he found Pro Archia and, in 1345 CE in Verona, his Letters to Atticus.

Petrarch continued to write for the next 25 years building up an impressive catalogue of scholarship. He even rejected an offer from his great friend the poet and scholar Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375 CE) of a post at the University of Florence. Still travelling around, Petrarch had fallen out with the Pope at Avignon and so moved on to Milan. Eight years later he moved to Padua but left after a year in 1361 CE. Trying to avoid the Black Death and ending up in Venice, the poet was at least given a house in exchange for leaving in his will his personal library to the city. In 1367 CE he moved for the last time to the seclusion of Arquà in the hills just outside Padua.

Later works by Petrarch focussed on philosophical themes such as moral perfection, and he was especially interested in the ancient Roman idea of virtus (virtue or excellence) and civic duty. Petrarch suffered a stroke in 1370 CE in Ferrara while travelling on his way to Rome. He recovered and continued to write but died in July 1374 CE at his home outside Padua, appropriately enough, while working at his desk. When his body was discovered his head was resting on a manuscript by the Roman author Virgil (70-19 BCE). Petrarch was buried at Arquà.

Romantic Poetry

Petrarch's interest in classical literature was reflected in his own Latin verse and sonnets. His earliest poems, written while he was a law student, were on the theme of the death of his mother. Petrarch's most famous work is his collection of poems written on the theme of love for an unattainable woman called 'Laura', his Canzoniere (Sonnets). The poet met this woman in church in Avignon in 1327 CE, but he never revealed who she was, and she has never been successfully identified by scholars ever since. Laura died of the Black Death plague in 1348 CE. These 366 love poems, sonnets, and songs, which are also collectively known as the Rerum Fragmentum Vulgarium (Vernacular Pieces), were written in the Tuscan vernacular with extra vocabulary from other Italian dialects. They cover the themes of unrequited love, lost love, and regret, amongst others. Petrarch revised his poems, even his very earliest ones, throughout his life right up to his death.

Breeze, blowing that blonde curling hair,

stirring it, and being softly stirred in turn,

scattering that sweet gold about, then

gathering it, in a lovely knot of curls again,

you linger around bright eyes whose loving sting

pierces me so, till I feel it and weep,

and I wander searching for my treasure,

like a creature that often shies and kicks:

now I seem to find her, now I realise

she's far away, now I'm comforted, now despair,

now longing for her, now truly seeing her.

Happy air, remain here with your

living rays: and you, clear running stream,

why can't I exchange my path for yours?

(Sonnet, 227, A. S. Kline translation)

Other Major Works

Petrarch wrote many works, mostly in Latin, in a long writing career and here below only some of his most important are considered. He edited the most complete version yet of the History of Rome by the Roman author Livy (59 BCE - 17 CE). Petrarch covered history himself when he composed an epic poem on the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE) between Rome and Carthage called Africa. The epic focuses on the life of the great Roman general Scipio Africanus the Elder (236-183 BCE). In 1336 CE he produced a collection of works by Virgil. Petrarch's De viris illustribus (On Illustrious Men) was a series of biographies on famous figures from the past, including the Old Testament's Adam and many Roman figures. The work was extensive but never completed. Yet another historical collection was the Rerum memorandarum libri (Of Memorable Things), also never completed.

Religious questions continued to interest the author. The Secretum meum (c. 1343 CE) has Petrarch in conversation with Saint Augustine while Truth looks on. The work confirms the author retained his religious beliefs which he believed were compatible with a life of scholarship in secular matters. The allegorical poem Trionfi (Triumphs) was worked on between 1351 and 1374 CE but never finished. It tells of the passage of the human soul towards enlightenment and knowledge of God. Philosophical works like De remediis utriusque fortunae (Remedies for Fortune Fair and Foul) helped revive an interest in Stoicism. Finally, aware of his own fame, Petrarch wrote a series of autobiographical texts collected as the Posteritati (Letter to Posterity) in the mid-1350s CE.

Influence on the Renaissance

The consideration of themes like virtue in civic life, his study of ancient texts, the rediscovery of lost ancient manuscripts, and his rejection of scholasticism are all reasons why Petrarch is considered one of the early founders of the Renaissance movement. During the early Renaissance, looking back at antiquity for inspiration was considered the best way to move forward in thought, art, and architecture. Petrarch was, then, one of the earliest to have done this. The poet even went so far as to imitate Cicero's letters in his own works as he wrote pieces addressed to famous ancient scholars of the past, as well as contemporary ones and civic leaders.

Petrarch believed himself that a new golden age of thought and politics could be achieved by returning to the ideals of antiquity. His idea that the period in which he lived was an intermediary period between antiquity and this new dawn, what he called disparagingly media tempestas, media aetas, or media tempora ('the in-between period') or, in one poem, a 'slumber', was latched onto by later Renaissance thinkers and did much to foster the idea that the Middle Ages was somehow a period of cultural darkness. It is an inaccurate view that many medievalist scholars have long sought to correct, but it has proven a stubborn misconception to shift, especially in popular culture.

In addition, in such works as Contra Medicum (c. 1353 CE), Petrarch criticised the Christian medieval Church for demonising pagan antiquity and its achievements. Although not rejecting religious studies himself, Petrarch's work with ancient manuscripts encouraged the scholarship of non-religious subjects with humanity at its centre, and this became a legitimate activity for intellectuals. Consequently, Petrarch is often cited as the founder of humanism. So, too, Petrarch's use of letters as a form and medium of scholarship would have lasting consequences, making this format popular and creating a whole new secular community of scholars who had no connection with the Church or religious studies and who corresponded with each other in a geographically widespread community of ideas.

Lombardo della Seta (d. 1390 CE) was Petrarch's literary executor, and he created the first manuscript version of Petrarch's On Illustrious Men in 1379 CE. There was then a revival in interest in Petrarch when his works were edited and republished by the Venetian scholar Pietro Bembo (1470-1547 CE) in pocket-sized format in 1501 CE. Petrarch's literary style, known as Petrarchism, and his preference for Latin in scholarship helped continue the use of that language through the Renaissance. In contrast, Petrarch's preference for using the vernacular in romantic poetry and his use of sonnets influenced poets across Europe, deeply affecting Renaissance literature. Even artists strove to capture the classical beauty of Petrarch's elusive Laura with her blonde hair and alabaster skin in their paintings. Petrarch's shadow on the Renaissance was, then, long, even if it was not entirely in keeping with how he himself viewed this life and the next.