The Ptolemaic dynasty was a Macedonian royal family that ruled Ptolemaic Egypt from 323 to 30 BCE. It was founded by Ptolemy I, a general and successor of Alexander the Great. They built Alexandria, including the Lighthouse of Alexandria and the Great Library of Alexandria. The dynasty ended when Rome conquered Egypt in the reign of Cleopatra VII.

The dynasty presented themselves as both Greek kings and Egyptian pharaohs. They never assimilated into Egyptian culture, and their reign began a process of Greek immigration and acculturation in Egypt. The dynasty practiced incestuous marriage, with most rulers marrying close relatives.

The Ptolemaic Empire expanded rapidly before civil wars, territorial losses, and natural disasters weakened it in the 2nd century BCE. The final generations of Ptolemies were reliant on the Roman Republic for military support.

Origins

The Ptolemaic dynasty was founded by Ptolemy I (336-282 BCE), son of Macedonian nobles Lagos and Arsinoe. Ptolemy was one of Alexander's somatophylakes, trusted bodyguards and generals. The dynasty later encouraged a myth that Ptolemy was really the illegitimate son of Philip II of Macedon (r. 359-336 BCE), making him Alexander the Great's half-brother.

Ptolemy was present during Alexander's conquest of Egypt (332 BCE), which was under the oppressive rule of the Achaemenid Empire. Alexander was welcomed by the Egyptian people and proclaimed pharaoh in Memphis. He made offerings to the Egyptian gods, demonstrating his desire to uphold Egyptian tradition, a policy that the Ptolemies would imitate. He also founded Alexandria, a classical Greek city on the coast of Egypt.

[Alexander] reached Egypt late in the year, remaining there until spring, [and] visited the oracle of Ammon. But perhaps more significant for the future was Alexander's assumption of the religious titles and honors of the Egyptian king, especially upholding the kingship's linkage to the god Ptah, which ensured the lasting support of his priesthood, a significant factor that continued into the time of Cleopatra.

(Chauveau, chapter 2)

The death of Alexander the Great in Babylon in 323 BCE created a dispute over who would inherit his empire. His half-brother Philip Arrhidaeus was eventually named king, and Alexander and Roxanne's son Alexander IV of Macedon became co-ruler after his birth. Perdiccas took the role of regent, making him effectively its ruler. Alexander's generals, called the Diadochi (lit. "successors" in Greek), became satraps of its provinces. Ptolemy was made satrap of Egypt, the wealthiest and most desirable province.

The Diadochi, including Ptolemy, Seleucus I Nicator, Lysimachus, Crateros, and Antipater, resisted Perdiccas' attempts to control them. In 321 BCE, Ptolemy stole Alexander's mummified body from Perdiccas, who was attempting to bring it back to Macedon. Ptolemy buried Alexander in Memphis, later moving the body to Alexandria, to strengthen his connection to Alexander's legacy. This theft escalated the tension between Ptolemy and Perdiccas, who unsuccessfully attempted to invade Egypt and was killed by his own mutinying troops.

Philip Arrhidaeus was murdered in 317 BCE, followed by Alexander IV in 310 BCE. The Diadochi finally proclaimed themselves autonomous kings in 306 BCE. This act formally established the Ptolemaic dynasty, which ruled for another 300 years. The Wars of the Diadochi and their descendants fighting over territory resulted in the Syrian Wars (274-168 BCE) fought between the Ptolemies and the Seleucid Empire. Ptolemy I conquered Cyprus, Cyrene, Coele-Syria, and Phoenicia, forming the basis of the Ptolemaic Empire.

Ptolemaic Kingship

The Ptolemies maintained power through a combination of violence and diplomacy. They formed close relationships with Egyptian elites, especially the priesthoods, to reinforce their political and religious legitimacy. They also settled Greek military colonies throughout the country to quiet rebellion. Each king was named Ptolemy, and queens were named Berenike, Arsinoe, or Cleopatra. Modern historians number them, but in antiquity, they were distinguished by nicknames.

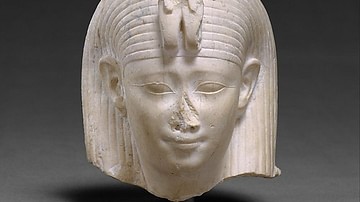

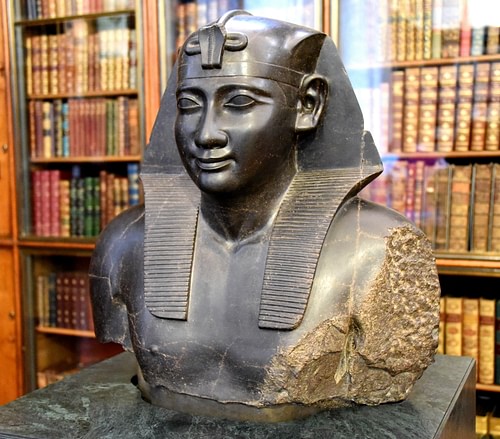

Ptolemaic royal ideology blended features of Macedonian and Egyptian kingship. Rulers used the Greek title basileus (king) or basilissa (queen), and the Egyptian title pharaoh. On coins circulated throughout their empire, the Ptolemies wear the Macedonian diadem, while in Egyptian statuary they wear Pharaonic regalia like the Egyptian double-crown. Other art depicting the Ptolemies combines Macedonian and Egyptian regalia.

The most important feature in the history of Ptolemaic ideology is the fact that the king, like the people of his kingdom, has two faces: one that is pharaonic and another that is Greek-Macedonian.

(Hölbl, 308)

The dynasty united their Greek and Egyptian subjects through a royal cult. Religious propaganda presented them as savior gods (theoi soteroi), who liberated those under their rule. The principle of euergetism, or royal charity, was central to this propaganda. Monarchs demonstrated charity by building temples, gymnasia, and libraries, and giving aid to the poor. They also established a cult of Alexander, which venerated him as the empire's patron god.

Court Culture

The Ptolemaic dynasty preserved Greek cultural habits instead of assimilating into Egyptian culture. The pages, courtiers, and tutors serving the royal family were typically Greeks. The dynasty only spoke Greek – except for Cleopatra VII – and so Egyptian aristocrats had to learn Greek to interact with their rulers.

Monarchs were coronated in Memphis but lived in Alexandria, one of the largest and most sophisticated cities of its era. The dynasty established themselves as patrons of Hellenistic culture and flaunted their wealth through festivals and monument construction. The crown jewels of these efforts were the Great Library and the Lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Ptolemaic royal women were unusually politically powerful for their era, and many ruled independently, like the famous Cleopatra VII. Like Macedonian and Egyptian kings, the Ptolemies had multiple wives and mistresses. Children born out of wedlock could be crowned, and the Ptolemies also often named one of their younger children heir, leading to civil wars.

Sibling Marriage

The dynasty practiced incestuous marriage; monarchs married a sibling or other close relative to be their co-ruler. The exceptions were political unions, like when the Seleucid princess Cleopatra I (r. 195-176 BCE) married Ptolemy V (r. 205-180 BCE). Ancient Greek and Roman sources claimed this was an Egyptian custom adopted by the Ptolemies. Modern historians generally reject this explanation because incestuous marriage was infrequent in pre-Ptolemaic Egyptian dynasties.

The first Ptolemaic sibling marriage was between Ptolemy II Philadelphus ("Sibling-Loving") and Arsinoe II Philadelphus. This union formed the basis of the royal cult, elevating the king and queen to the status of sibling gods. This ideology built upon the precedent of Greek and Egyptian gods who married their siblings, like Zeus and Hera or Isis and Osiris. Their union produced no children, but Ptolemy II already had heirs from a previous marriage. The practice was revived by Ptolemy IV and his descendants.

Historians have presented multiple theories for why this tradition persisted. Symbolically, it demonstrated that they were above the normal rules applied to mere mortals, equating them with gods. On a practical level, this limited competition for the crown by marrying potential rivals, and prevented princesses from having to marry husbands of a lower status.

As a result of inbreeding, the Ptolemaic dynasty remained mostly ethnically Macedonian. It is not known if the Ptolemies suffered health problems from inbreeding; the obesity and alcoholism common to the family were probably lifestyle-related. However, this familial dynamic certainly contributed to violent dynastic disputes.

Consolidation under Ptolemy II & Ptolemy III

The 3rd century BCE was a golden age for the Ptolemaic Empire, which spread into Nubia, Greece, Mesopotamia, and the Red Sea under Ptolemy II and Ptolemy III Euergetes ("Benefactor"). The province of Coele-Syria, which produced timber for shipbuilding and silver for paying armies, was key to this military expansion. Ptolemy II's daughter Berenike Syra (r. 252-246 BCE) married the Seleucid king Antiochus III (r. 261-246 BCE), creating temporary peace between their dynasties. Their imperial power was celebrated in the Ptolemaia, a religious festival established by Ptolemy II.

Ptolemy II experienced a few military setbacks in his reign. The city-state of Cyrene seceded under his half-brother Magas, not to be regained until his son Ptolemy III (r. 246-222 BCE) married Magas' daughter Berenike II. Ptolemy II's attempts to meddle in Greek and Macedonian politics bore mixed results. He led the League of Islanders in the Cyclades and supported the unsuccessful rebellion against Macedon in the Chremonidean War (267-261 BCE).

The empire reached its greatest extent under Ptolemy III whose best-known campaign was the Laodicean War. The war began when Antiochus II died, causing a dispute between Berenike Syra and Antiochus' former wife Laodice I, each of whom expected their own son to inherit the throne. Ptolemy III brought a small army to the Seleucid capital Antioch in 246 BCE to help his sister take the throne. He was welcomed by the city officials, who supported Berenike. Unbeknownst to anyone, Laodice had already murdered Berenike and her son. Upon learning of this, Ptolemy III used his forces to invade Seleucid Mesopotamia, capturing several strategic cities.

Syrian Wars & Rebellion

After Ptolemy III's death and the coronation of Ptolemy IV Philopator ("Father-Loving", r. c. 222-205 BCE), Antiochus III recaptured Seleucia-in-Pieria and invaded Egypt. His onslaught was stopped by Ptolemy IV at the decisive Battle of Raphia in 217 BCE. Ptolemy IV and his sister-wife Arsinoe III were later murdered in 205 BCE by a conspiracy involving the regent Sosibius, Ptolemy IV's mistress Agathocleia, and her brother Agathocles. The conspirators ruled as regents to the dead rulers' 5-year-old son Ptolemy V Epiphanes ("God Who Appears") but were lynched by a military coup in 203 BCE.

By this time, the Ptolemaic military was increasingly reliant on harsh taxation and conscription policies which exploited the Egyptian population. Upon Ptolemy IV's death, the self-proclaimed pharaohs Horwennefer (r. 205-197 BCE) and Ankhwennefer (r. 197-185 BCE) led a revolt against Greek rule. Meroitic Nubia supported the rebels to weaken the Ptolemies. Antiochus III and Philip V of Macedon allied to divide the Ptolemaic Empire amidst the turmoil. Forced to fight on multiple fronts, the Ptolemaic army lost its eastern territories and was crushed by the Seleucids at the Battle of Panium (200 BCE).

Ptolemy V ended the conflict by marrying Antiochus III's daughter Cleopatra I Syra in 195 BCE. This allowed Ptolemy V to focus on defeating Ankhwennefer in 185 BCE and annexing part of Nubia. He established a stronger military presence in Upper Egypt and also made amends for the causes of rebellion by lowering taxes, abolishing naval conscription, and giving privileges to the priesthoods. Ptolemy V planned to retake territory in Syria after the death of Antiochus III, but his generals poisoned him in 180 BCE. Cleopatra I ruled afterward as regent to their infant son Ptolemy VI Philometor ("Mother-Loving").

Ancient authors like Polybius considered the fragmentation of the Ptolemaic Empire to be a reflection of increasingly cruel, lazy, and immoral kings. Modern historians associate Ptolemaic losses with larger factors like social tensions within Egypt and the better political organization of the Seleucids in the 3rd century BCE. Historian J. G. Manning demonstrated a correlation between droughts caused by volcanic climate change and Egyptian revolts, indicating that environmental change might have weakened the Ptolemaic state. The later Ptolemies were unable to hold external territories but secured their control of Egypt through stronger ties with Egyptian elites.

Civil Wars

After Cleopatra I's death in 176 BCE, the kingdom passed to the young siblings Ptolemy VI, his sister-wife Cleopatra II, and their younger brother Ptolemy VIII Euergetes. They attempted to invade Syria, resulting in a swift counterinvasion by Antiochus IV who captured Memphis and was crowned pharaoh in 168 BCE. He would have taken Alexandria and ended the Ptolemaic dynasty had the Roman ambassador Gaius Popilius Laenas not intervened by threatening to declare war if Alexandria were attacked.

With Rome defending them from the Seleucids, Ptolemy VI and Ptolemy VIII turned against each other. Ptolemy VIII defeated his older brother, who sought sanctuary in Rome. Ptolemy VIII was remembered by ancient accounts as a highly intelligent and hedonistic ruler whose brutality made him unpopular. Ptolemy VI soon returned from exile to oppose him. In 160 BCE, the Roman Senate suggested dividing the Ptolemaic Empire; Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II ruled Egypt and Cyprus, while Ptolemy VIII ruled Cyrene. Ptolemy VIII later made a will bequeathing his kingdom to the Roman Republic on his death, in exchange for Roman protection.

Egypt experienced relative stability and prosperity under Ptolemy VI. In 145 BCE, he invaded the Seleucid Empire to help his son-in-law Alexander Balas fight Demetrius II. After being betrayed by Balas, Ptolemy VI switched sides and captured Antioch. Ptolemy VI was offered the Seleucid crown but declined to avoid alienating Rome. Demetrius II was crowned in his stead. Ptolemaic forces were successful in a final battle against Balas, but Ptolemy VI died after falling from his horse.

Ptolemy VIII returned to Alexandria after his brother's death and married Cleopatra II. They had several children, including Ptolemy Memphites who was born during Ptolemy VIII's coronation in 143 BCE. Ptolemy VIII quickly began eliminating all who opposed his reign. A respected scholar in his own right, he purged the Library of Alexandria of scholars who criticized him. In 141 BCE, Ptolemy VIII married his niece and stepdaughter Cleopatra III, the daughter of Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II.

The rivalry between Cleopatra II and Cleopatra III started another civil war. Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra III fled to Cyprus, where he killed his son Ptolemy Memphites to prevent the boy from becoming a rival. Meanwhile, prolonged civil war and droughts caused anarchy and deprivation in Egypt. Peace was eventually reached between the three monarchs in 124 BCE, and conditions in Egypt slowly normalized. A poorly attested king, called Ptolemy VII by modern historians, is mentioned in ancient sources. He was likely either Ptolemy Memphites or a son of Ptolemy VI and was named king posthumously to make amends for his murder.

Roman Domination

Ptolemy VIII died in 116 BCE, leaving behind numerous heirs and a kingdom reliant on Roman support. His illegitimate son Ptolemy Apion became king of Cyrene, which was bequeathed to Rome upon Apion's death. Cleopatra II's son Ptolemy IX Soter II took Egypt and Cyprus, defeating Cleopatra III's son Ptolemy X Alexander, who made a will bequeathing his kingdom to Rome. He soon died trying to retake the kingdom with a mercenary army, leaving Ptolemy IX's reign uncontested.

After Ptolemy IX died of natural causes, the Roman Senate chose not to annex Egypt, instead giving it to Ptolemy XI Alexander II, Ptolemy X's illegitimate son. Ptolemy XI had spent some of his early years in Rome, being mentored by the Roman dictator Sulla. Sulla supported his return to Egypt, where he married his stepmother Cleopatra Berenike and became king. His reign was brief; he was lynched by a mob after it became known that he had killed his new wife.

Three illegitimate children of Ptolemy IX were crowned as his successors. Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos ("New Dionysus") and his sister-wife Cleopatra VI ruled Egypt, while their brother Ptolemy ruled Cyprus. In 58 BCE, the Roman Republic violently annexed Cyprus for its grain. Ptolemy XII's lack of response to this act of aggression made him unpopular, and he was usurped by Cleopatra VI and their daughter Berenike IV. He borrowed enormous amounts of money from Roman creditors so that he could pay for an army to retake Egypt. He was restored to his throne by the Roman governor of Syria Aulus Gabinius in 55 BCE, afterward relying on Roman mercenaries to stay in power.

Resurgence & Fall under Cleopatra VII

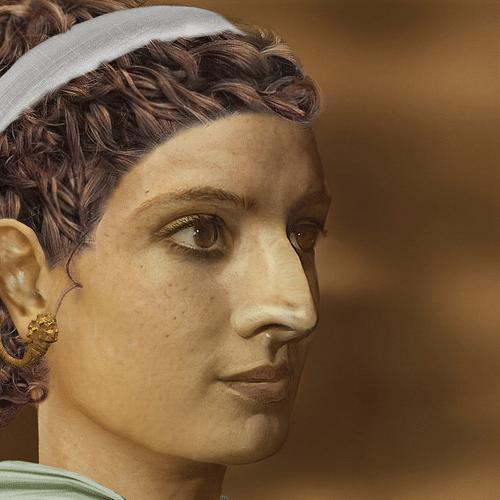

Ptolemy XII was succeeded by Cleopatra VII Philopator and Ptolemy XIII. She is the most famous member of the dynasty, described in ancient accounts as charismatic, ruthless, and intelligent. According to Plutarch, she was the only member of the dynasty to learn the Egyptian language. Her ally and lover Julius Caesar, dictator of Rome, helped her to defeat Ptolemy XIII in the Alexandrian War. Before the assassination of Julius Caesar on the Ides of March, they had allegedly had a son named Caesarion.

Later, her relationship with the Roman triumvir Mark Antony united Rome's eastern provinces and the Ptolemaic Kingdom, effectively giving the pair full control of the eastern Mediterranean. In 34 BCE, Antony ceded vast swathes of Roman territory to Cleopatra and their children, restoring the Ptolemaic Empire to its greatest extent since the 3rd century BCE. This made Antony appear disloyal to Rome and worsened tensions between him and his former brother-in-law Octavian.

In 32 BCE, the Roman Senate declared war on Antony and Cleopatra at Octavian's instigation. Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide after their defeat at the Battle of Actium in 30 BCE. Octavian annexed Egypt, executing Cleopatra's heir Caesarion, and taking her other children hostage.

Legacy

The Ptolemaic dynasty was the longest-lasting successor to Alexander's empire. Ancient historians remembered them for their greed and brutality, but Egypt flourished under them. Royal sponsorship of Greek culture and immigration began a period of Hellenization that reshaped Egyptian society. Alexandria was the center of the Hellenistic world, fostering a culture of scientific inquiry that produced breakthroughs in engineering, natural science, and medicine. Increased trade also exported Egyptian culture throughout the Mediterranean.

While Cleopatra's death is considered the end of the Ptolemaic dynasty, her daughter Cleopatra Selene II and grandson Ptolemy of Mauretania remained prominent in the Roman Empire. Some historians have suggested that the descendants of the dynasty might have married into the royal family of Emesa, making them ancestors of the Roman empress Julia Domna and the Roman emperor Caracalla.