Ptolemaic Egypt existed between 323 and 30 BCE when Egypt was ruled by the Macedonian Ptolemaic dynasty. During the Ptolemaic period, Egyptian society changed as Greek immigrants introduced a new language, religious pantheon, and way of life to Egypt. The Ptolemaic capital Alexandria became the premier city of the Hellenistic world, known for its Great Library and the Pharos lighthouse.

From Persian Rule to Alexander

In 525 BCE, Egypt was conquered by the Achaemenid Empire, beginning a period of harsh foreign rule and cultural repression. Egypt briefly regained its independence from 404 BCE until 342 BCE before it was reconquered. Discontent with the Persian government resulted in the Egyptians welcoming Alexander the Great as a liberator when he invaded in 332 BCE. Alexander had already broken the Persian army at the Battle of Issus (333 BCE), and Mazakes, the satrap of Egypt, surrendered without a fight.

Alexander demonstrated a deep respect for Egyptian culture, choosing to be crowned pharaoh according to traditional custom. He offered sacrifices to the Egyptian gods in Heliopolis and Memphis and hosted Greek athletic games to celebrate his reign. Next, he traveled south to the Oracle of Amun, whom the Greeks equated with Zeus, in the Siwa Oasis. Alexander believed himself to be the son of Zeus, which the oracle seemingly confirmed for him. The idea had precedent in Egyptian royal ideology in which kings were considered living gods, the offspring of deities like Ra or Amun. It was an unusually grandiose claim for Greek rulers, but Alexander's reputation was great enough for the Greeks to accept him as a demigod.

Alexander's grand design will slowly have come to encompass the idea that all peoples were to be subjugated for the formation of a new world order; for this purpose, the Egyptian pharaonic system presented a very suitable ideology that was well established and has been accepted for millennia.

(Hölbl, 9)

In 331 BCE, Alexander visited the fishing village of Rhakotis where he planned the foundation of a new city, Alexandria. He intended for Alexandria to be the capital of his empire, a link between Egypt and the Mediterranean. Before leaving to continue his conquests, Alexander appointed two governors, Doloaspis and Peteisis, and named Cleomenes of Naukratis, a Greek Egyptian, as his satrap. He also left a small army to occupy and defend Egypt.

After the death of Alexander the Great in Babylon in 323 BCE, his general Ptolemy I became satrap of Egypt. He was nominally the servant of Alexander's successors Philip Arrhidaeus and Alexander IV of Macedon, but in reality, he ruled on his own initiative. Ptolemy I quickly executed Cleomenes, whose exorbitant taxation was unpopular, and began establishing royal policies to modernize the country. By 310 BCE, the last of Alexander's heirs had died, and during the Wars of the Diadochi, Alexander's generals claimed pieces of his empire. Ptolemy I was crowned king of Egypt in 306 BCE, establishing the Ptolemaic dynasty.

Government

At the time of Alexander's conquest, Egypt had an efficient system of government that was thousands of years old. Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II left this system mostly intact except for changes meant to modernize the country. Ancient Egypt was traditionally divided into roughly 40 provinces called nomes, each with its own capital. The Egyptian nomarchs, or governors, retained their positions under Macedonian rule. However, they had to answer to the strategoi (lit. "generals") appointed by the Ptolemies to oversee the nomes. Towns and villages were run by municipal officials who reported to the strategoi.

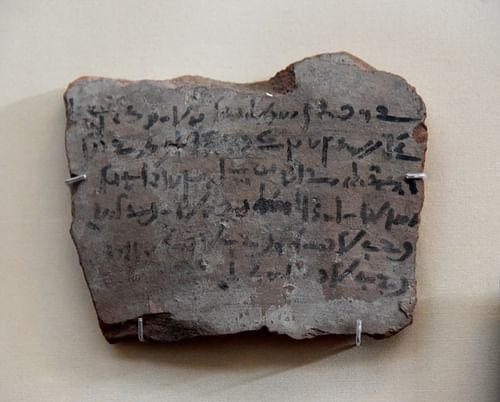

Because the Ptolemies spoke Greek, Greek became the official language used by the royal administration. Demotic Egyptian remained the primary language used by the local government and the main population. Egyptian scribes and officials had to become bilingual to interact with the Greek-speaking royals.

The Ptolemaic state, within its core territory, was neither an Egyptian, nor a Greek state. Indeed, it combined the traditions of the Egyptian monarchy—the ancient agricultural system, political control through the division of the country into nomes, and the ancient temples and priesthoods—with Greek fiscal institutions that derive most immediately from the fourth century BC.

(Manning, 3)

Two separate legal systems, one based on Egyptian law and the other on Greek law, existed in Ptolemaic Egypt, and people often chose whichever court they felt would give them a more beneficial ruling. In 118 BCE, Ptolemy VIII declared that Egyptian law applied to all contracts written in Demotic, and Greek law applied to all Greek contracts.

A network of interconnected offices handled governance, taxation, and law enforcement in Ptolemaic Egypt. Scribes were responsible for distributing royal edicts and other government communications, and receiving petitions from civilians. At the national level, the Ptolemies appointed ministers to oversee the day-to-day management of the kingdom. These ministers included the dioiketes (the economic minister) and basilikos grammateus (royal scribes). Many of the highest officials were Greeks, with close ties to the royal family. Aristocratic Egyptian advisors, hailing from Pharaonic and priestly families, were used for their knowledge of Egyptian culture and society.

Regional Development

Ptolemaic Egypt had a population of at least 3 million people owing to the surpluses of food and drink in ancient Egypt. Most of this population lived along the Nile, while the desert regions beyond remained sparsely populated. The population density in the inhabited areas was comparable to modern-day France, resulting in a relatively high level of urbanization.

To a foreign visitor, the Egyptian countryside must have seemed like a nearly uninterrupted sequence of teeming villages situated at a distance of no more than 2-2.5 miles from one another and housing sometimes more than a thousand people.

(Chauveau, 35)

The country was roughly divided into two distinct regions: Lower Egypt (the northern region encompassing the Nile Delta) and Upper Egypt (the southern region surrounding the Nile Valley). Lower Egypt had a denser, more urbanized population sustained by the fertile floodplains of the Delta. Its proximity to Alexandria and the Mediterranean meant that most Greeks settled there. The Ptolemies founded several port cities on Lower Egypt's Red Sea coast.

There were three Greek city-states in Ptolemaic Egypt: Alexandria, Naukratis, and Ptolemais Hermiou. Naukratis was a port city founded in the 7th century BCE as a colony for Greek traders and mercenaries in Egypt. Ptolemais Hermiou was founded by Ptolemy I to replace Thebes as the capital of the Thebaid. It was the primary Hellenistic settlement in Upper Egypt. These cities had constitutions and elected councils, although they were still subject to Ptolemaic rule. Their citizens had additional rights and privileges, owing to their more democratic nature. As in most ancient cities, the vast majority of residents were non-citizens.

Upper Egypt was more rural, and its culture was not strongly affected by Hellenization. Thebes and Memphis, both of which had formerly been Egypt's capital, were Upper Egypt's foremost cities. Memphis thrived under the Ptolemies as an industrial and commercial hub. Thebes' status as a provincial capital was lost when Ptolemy I founded its replacement, Ptolemais Hermiou. Thebes subsequently declined in importance and was frequently a cradle of rebellion against the Ptolemies.

The Fayum, a marshy region in Upper Egypt, rose to prominence in this period. The Ptolemaic dynasty undertook a massive land reclamation program that drained water bodies like Lake Moeris to create additional farmland. This became one of the primary settlements for Ptolemaic cleruchs, or military settlers. A sophisticated system of canals and dikes provided irrigation, allowing Greek settlers to plant grapes and olives.

Religion

As in earlier periods of Egyptian history, the priests and temples were politically influential. In addition to performing traditional religious rituals, the temples also filled the role of regional government. They directed the planting and harvest of crops, collected taxes, and administered the law. In the Ptolemaic period, priests from throughout Egypt gathered at annual synods to discuss religious and political matters.

The Ptolemaic dynasty relied on the priesthoods' support to legitimize them as rightful pharaohs in the eyes of the people. In return, the royal family gave the priesthoods funding for prestigious temples and monuments. The Ptolemaic dynasty had a particularly close relationship with the priests of Ptah in Memphis, whose loyalty to the Ptolemies was rewarded with political influence. Other temples sometimes opposed Ptolemaic rule, inspiring rebels and usurpers.

Ptolemy I established a cult of Alexander, worshipping him as a founder and patron deity. Ptolemy I himself was given divine honors by the people of Rhodes as thanks for defending them against Demetrius I of Macedon and later began to present himself as a god-king comparable to Alexander. In the early 3rd century BCE, Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II Philadelphus established the royal cult, which venerated living and dead members of the Ptolemaic family.

Greek immigrants equated Egyptian deities with Greek gods through a process called interpretatio graeca. For example, Anubis was compared to Hermes, Isis to Aphrodite, and Osiris to Dionysus. Greek influences intermingled with Egyptian religion, resulting in the creation of hybrid gods. Some new gods, like Serapis, were created by the Ptolemies to unify their Greek and Egyptian subjects. Others were the result of natural interactions between Greeks and Egyptians.

Immigration & Hellenization

Between the 4th and 3rd century BCE, hundreds of thousands of Greeks immigrated to Ptolemaic Egypt. Jews, Thracians, Carians, and Syrians also immigrated in large numbers. The majority of these immigrants were cleruchs, soldiers given plots of land in exchange for service. Historians estimate that anywhere from 5-10% of Egypt's total population was Greek by the end of the 3rd century BCE. Immigration slowed to insignificant levels after this period, as the Greek population in Egypt stabilized.

Most of the Greek population was concentrated in Fayum and the Delta. Some immigrants founded new villages and garrison towns, while others moved into pre-existing settlements. New foundations were laid out like Greek cities on a grid street plan. The gymnasium was usually located at a central point in the city. Ancient Greek gymnasia were places of civic and athletic participation, strongly tied to Greek identity. Enrolment in the gymnasium was a marker of Greek identity and civic citizenship. Eligible males were typically enrolled at age 14. Other cultural institutions like politeuma and religious brotherhoods helped immigrants to create a sense of community and belonging.

Greeks remained a minority group within Egypt, even as 'being Greek' was slowly redefined as more a cultural and linguistic phenomenon than an ethnic one, and after a century of Ptolemaic rule, Hellenized Egyptians began to fill posts in the military and the bureaucracy.

(Rathbone, 24)

Immigrants to Egypt came from distinct regions like Macedon, Athens, Samos, Sparta, and Thessaly. Over time, the cultural distinctions between these groups lessened as they adopted a more universally 'Greek' identity. Some Egyptians also Hellenized by adopting the Greek language, culture, and even a Greek name. People considered Greek were privileged in business and politics. Greeks and Persians were also exempt from certain taxes. Hellenized Egyptians often served in the military or government, where speaking Greek was necessary. Intermarriage between Greeks and Egyptians further accelerated the process of Hellenization.

Alexandria

Alexandria thrived as the capital of Ptolemaic Egypt. It was a bustling trade center, strategically located on a series of natural harbors on the Mediterranean coast. The city had a cosmopolitan population of up to 300,000 residents, of whom maybe 10,000 were citizens. The three largest ethnic groups were Greeks, Egyptians, and Jews. Egyptians were probably the largest demographic, but Greek culture dominated the city. Immigrants from elsewhere in Europe, the Near East, East Africa, and India flocked to Alexandria as merchants, sailors, scholars, and mercenaries. In antiquity, Alexandria was sometimes considered separate from the rest of the country, referred to as "Alexandria next to Egypt".

Alexander left behind him both a Graeco-Macedonian army of occupation and a new city, Alexandria, which was destined to grow beyond all expectation – Alexandria, the city of Sarapis, which from the beginning and for a thousand years to come lived with a double destiny: Hellenism and the rule of Egypt.

(Bingen, 215)

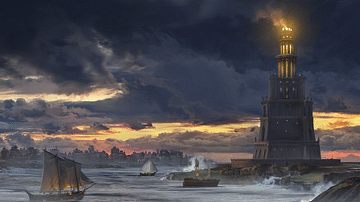

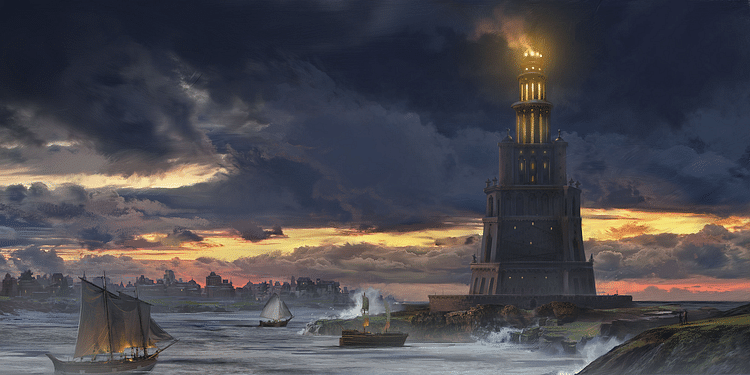

Alexandria was the focal point of Greek culture in Egypt and the cultural capital of the Greek world. The city was built along a grid street plan laid out by Alexander the Great, which was rapidly built up by the Ptolemies. The city was divided into three sections: the Royal or Greek Quarter, the Egyptian Quarter, and the Jewish Quarter. Hellenistic architecture dominated its buildings and monuments, albeit with Egyptian architectural influences. Ptolemy I and II oversaw the construction of the Pharos, the iconic lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Later generations of Ptolemies adorned the city with marble temples, mansions, and monumental tombs. Meanwhile, most of the city's inhabitants lived in cramped, hazardous tenements.

In antiquity, Alexandria was famous for its intellectual community, patronized by the royal family. The Museion, or Great Library of Alexandria was built under the direction of Demetrius of Phalerum, one of Aristotle's pupils. It attracted minds like Euclid, Eratosthenes, Theophrastus, and Hero of Alexandria. Its collection of Egyptian, Near Eastern, and Greek literature included hundreds of thousands of scrolls. Alexandrian literature helped to shape Ptolemaic national identity by situating Greek mythology and epic narratives in Egypt. The Jewish community of Alexandria also developed a unique literary culture, which influenced the development of Jewish and Christian literature in later periods.

Society & Economy

The economy of Ptolemaic Egypt changed dramatically from the Pharaonic period. The Ptolemies introduced a system of coinage, previously almost unknown in Egypt. Ptolemaic currency was modeled on ancient Greek coinage and used denominations of obols and drachmas. This allowed Egypt to participate in a Mediterranean-wide economy, and for the Ptolemaic dynasty to pay soldiers and traders in coins. Every aspect of production and property ownership was taxed, and individuals had to pay a head tax. The Ptolemies conducted censuses to keep track of taxable people and property.

Like in all preindustrial societies, most of the population were farmers. Egypt exported grain, fruit, and fiber crops. The ancient Egyptian diet was based around bread and beer, but Mediterranean products like wine began to be produced in greater volume for exportation or consumption by Greek immigrants. The royal government personally owned up to half of the farmland in Egypt, with the temples owning a significant portion of the remaining farmland. Only a small portion of farmland was owned by private individuals.

The labor of these farmers sustained a small ecosystem of craftspeople like potters, textile producers, carpenters, and masons. Life in the countryside was simple, with people typically living in mud-brick multi-story tower houses or small one-story dwellings. Wealthier residents built spacious villas out of marble and granite. The larger towns and cities were full of taverns, bathhouses, shops, and apartments.

Women in ancient Egypt had a greater level of economic and social freedom than in many contemporary societies. They could own businesses, live independently, and represent themselves in legal matters. This resulted from Egypt's relatively egalitarian society meeting with an emerging Hellenistic culture in which Greek women were far more liberated than their ancestors. However, they were not fully equal to men and were far less likely to be given a formal education.

Warfare & Rebellion

The Ptolemaic army and Ptolemaic navy were a Hellenistic military force originally based around veterans from the army of Alexander the Great. These soldiers came to Egypt seeking fortune and farmland. Many of their descendants continued to serve in the Ptolemaic military, supplemented by mercenaries. In later periods, the Ptolemies recruited more native Egyptian soldiers, who were paid less than Greek or barbarian troops but proved equally effective. For the first century of Ptolemaic reign, Egypt was mostly untouched by war. The Ptolemies at the time waged wars of conquest to expand their reach in Asia, Greece, and Nubia.

This changed at the end of the 3rd century BCE as rebellion broke out. The Ptolemaic Kingdom began to lose ground in the Syrian Wars against the Seleucid Empire, who repeatedly attempted to invade the country. Civil wars between rival members of the Ptolemaic dynasty disrupted trade and infrastructure, leading to breakdowns in law and order. The effects of war were especially devastating during the conflict between Ptolemy VIII, Cleopatra II, and Cleopatra III from c. 141 to 124 BCE.

Rebellions involving the army and royal guard cropped up throughout Ptolemaic history, forcing the ruling dynasty to bend to the will of its soldiers. The most dramatic revolt came after Ptolemy IV trained 30,000 Egyptian hoplites who helped defeat the Seleucids at the Battle of Raphia in 217 BCE. These hoplites later staged a rebellion in Upper Egypt, proclaiming two native Egyptian rulers: Horwennefer (205-197 BCE) and Ankhwennefer (197-185 BCE). These rebel kings were eventually defeated by Ptolemy V.

Roman Conquest & Aftermath

Ptolemaic Egypt's military capability diminished in the late 2nd century BCE, and it became increasingly reliant on Roman support. Ptolemy XII and his daughter Cleopatra VII relied on the Roman army to remain in power. Cleopatra's relationship with the Roman triumvir Mark Antony enabled her to expand Ptolemaic influence throughout the eastern Mediterranean. However, it also precipitated a war between the Roman Senate and Antony, which saw Antony and Cleopatra's forces destroyed by Augustus at the Battle of Actium in 30 BCE.

The kingdom was annexed by the Roman Empire and reorganized into the province of Roman Egypt. Greek and Egyptian culture continued to dominate society while the power of the priesthoods rapidly faded without royal patronage. Many of the economic policies of the Ptolemies were maintained by the Romans, and participation in the Roman world created more trade opportunities. Alexandria, still the capital of Roman Egypt, became second only to Rome in wealth and influence.