The Romans assimilated earlier Greek science for their own purposes, evaluating and then accepting or rejecting that which was most useful, much as they did in other fields such as warfare, art, and theatre. This assimilation of Greek thought began in the 2nd century BCE, and ideas often came with their practitioners. For example, the first specialist architects and doctors in the Roman world were very often Greek. The Roman respect for ancient Greek scholars continued right up to the end of the empire, and so Roman scientists, even if their own innovations were largely more concerned with refinements than new ideas outright, managed to document and record a long, ancient tradition of scientific thought, so preserving it for posterity. The old approach of historians that the Romans had no significant science of their own has now been reassessed to reflect their practical contributions to the evolution of fields like architecture, engineering, and medicine, which were underpinned by progress in such sciences as geometry, physics, and biology.

Attitudes to Science

One notable distinction of Roman scientists was their desire for authoritative answers to any questions they had about the world. In addition, for the practical Roman mind science had to provide useful information which could be used to ensure successful outcomes of real projects. Long and ultimately purposeless discussion and research on a purely theoretical level were not for the Roman scientist. Physics had to be of practical use to produce effective torsion catapults, biology must improve agricultural yields, and mathematics and geometry must combine to provide the best answers in order to build the most impressive domes and arches. This pursuit of scientific knowledge was very often sponsored by wealthy private individuals who sought the benefits of a reputation with the public as an active promoter of culture.

Roman Science Authors

A number of Roman authors stand out who attempted to study earlier Greek science and forge this body of knowledge with some new discoveries and theories into a corpus of practically useful ideas suitable for the Roman way of life:

- Cato (b. 234 BCE) – the famous orator also wrote a valuable treatise (De agricultura) which gave advice on how to run a good estate with notes on wine and oil production and various remedies for crop diseases.

- Varro (b. 116 BCE) – was the most prolific scientific author, although very little of his work survives. One exception is the Res Rusticae, which describes the best ways to manage a large estate. His other works on mathematics, geography, biology, and more, live on through his immense influence on later authors such as Vitruvius, Pliny, Augustine, and Martianus Capella.

- Cicero (b. 106 BCE) - famous as an orator and politician, his great contribution to science was putting the Greek corpus into Latin, and his works on philosophy proved especially influential in the field of cosmology and physics.

- Julius Caesar (b. 100 BCE) - his Gallic Wars included much on geography, and he composed a lost work on the stars.

- Lucretius (b. c. 94 BCE) - wrote De rerum natura on the major Greek works of atomist philosophy and was especially interested in optics and biology.

- Nigidius (1st century BCE) - wrote works (which survive only in fragments) on astronomy, zoology, weather, and human nature.

- Vitruvius (1st century BCE) - wrote an influential work on architecture (De architectura) which included surveying, town planning, mathematics, principles of proportion, materials, astronomy, and mechanics.

- Seneca - his work on natural philosophy included studies of meteorology, earthquakes, volcanoes, comets, and meteors.

- Columella (b. 50 CE) – wrote the most comprehensive manual on agricultural best practice. The 12 books, designed to advise large estate owners, covered such areas as viticulture, horticulture, animal husbandry, farm calendars, and the best layout for a villa.

- Marcus Manilius (1st century CE) - wrote five volumes on astrology, his Astronomica.

- Pomponius Mela (1st century CE) - composed an extensive survey of Mediterranean and north European geography published in his three-volume De chorographia.

- Aulus Cornelius Celsus (1st century CE) - who compiled a vast encyclopedia, eight volumes of which, the De medicina, examined medical science (old and new) and such topics as diet, therapy, and surgery.

- Scribonius Largus (b. c. 1 CE) - compiled a handbook, the Compositones (Prescriptions), of medical remedies especially useful for gladiators.

- Pliny the Elder (b. c. 23 CE) - compiled a 36 volume encyclopedia, the Naturalis Historia, on the natural world – animal, vegetable, and mineral. He himself claimed that his work contained no fewer than 20,000 facts.

- Frontinus (d. c. 103 CE) - composed works on military science, especially war machines, and wrote on the water systems of Rome in his De acquis urbis Romae.

- Galen (b. 129 CE) – of Greek origin who became a physician to emperors after starting his career administering medical aid to gladiators. He is an invaluable source on earlier medical matters, notably Hippocrates, but was also a successful practitioner of complex surgeries himself.

Late-Empire Attitudes to Science

In the mid-3rd century CE, scientific thought was transformed, along with religion and philosophy, by the Neoplatonist thinkers Plotinos of Egypt and Porphyry of Syria. One of the many subsequent Neoplatonist scholars, to illustrate the breadth of subjects they discussed, was Martianus Capella (c. 430 CE) who wrote on geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, music theory, and geography. In addition to this new approach, the monotheism of Christianity had spread to become the official state religion by the 4th century CE. Christians were wary of any scientific theories contrary to their view of the universe, but the two positions were not necessarily antagonistic, and several important scientists were actually Christians, for example Calcidius (c. 375 CE) who wrote widely on cosmology.

Medical scientists continued to be prolific authors. Notable names from the period are Marcellus of Bordeaux (c. 400 CE), who wrote a vast collection of remedies, and Theodorus Priscianus, Caelius Aurelianus (c. 450 CE), and Vegetius, who all drew on earlier, often now lost, works. By the 5th century CE and the collapse of the Western empire, Roman science ceased to possess any identifiable character, but two authors who stand out from the period are Cassiodorus Senator (485 CE) and Boethius (c. 520 CE), who both, once again, displayed the Roman reverence for Greek sources and tradition.

Scientific Achievements

Architecture

The Romans adopted the Greek architectural orders, added the composite capital and Tuscan column to the repertoire, and generally made their buildings much more intricately decorative. Ambitious in their monumental building projects, they were driven to use bricks in new ways, to build wide-spanning arches and supporting buttresses, even to invent a new type of concrete which was light-weight enough for large domes and water-resistant enough for harbour moles. New types of buildings appeared such as the basilica, triumphal arch, monumental aqueduct, amphitheatre, and granary building. There were also huge bath complexes with rooms of differing temperatures and under-heated floors and pools, and multistory residential housing blocks for the poorer classes. Such projects required complex designs using wide-ranging mathematical skills and the result was an emphasis no longer merely on the structure and blocks of the building but on the magnificence of the space these materials enclosed.

Astronomy & Astrology

The Romans adopted much of what the Greeks and Ptolemaic Egypt had achieved previously in the field of astronomy. Measuring time using sundials did become more accurate in the Roman period when even portable sundials became popular, sometimes with changeable discs to compensate for changes in location. Public sundials were present in all major towns, and their popularity is evidenced in archaeological finds such as 35 from Pompeii alone. A seven-day astrological week was adopted during the reign of Augustus.

Astrology, also adopted from Ptolemaic Egypt, was popular with the Romans, and as in many other ancient cultures, the link between the movements of celestial bodies and the signs of the zodiac with the human experience was taken as certain (even if there were a few sceptics amongst scholars). Astrologists were often used by emperors to demonstrate to the populace that their decisions and policies were always the best ones, although Augustus prohibited them giving consultations to private citizens.

The Romans were well aware, as documented in the work of Columella amongst others, of the importance of climate, soil type, and land formation in ensuring the best production results. Techniques familiar to 19th-century CE European farmers were used effectively by the Romans, such as crop rotation, pruning, grafting, seed selection, drainage, irrigation, and manuring. Some specialised industries such as viticulture easily matched the output of 20th-century CE producers. Tools were developed ranging from wheeled ploughs to oxen-drawn harvesting machines which dramatically improved efficiency. Grinding mills (and sieves) developed to produce finer flour for bread-making, and buildings were purpose-built to better store harvests. Farmers knew the value of greenhouses and even experimented with genetic modifications such as crossing apples with pumpkins.

Animal husbandry skills developed too so that sheep, cows, goats, poultry, and pigs were reared with success. Their size and the quality of wool are evidence that the Romans were as expert as any animal breeders before or since. Game such as rabbit, hare, boar, and deer were successfully farmed in large enclosed areas of forest. Fish and sea life were similarly farmed in artificial and controlled environments, where water was changed regularly (sometimes even heated) and the best artificial feed developed. The Romans also became adept at preserving their food using all manner of techniques such as smoking, salting, drying, curing, pickling in brine or vinegar, and storing in honey.

Engineering

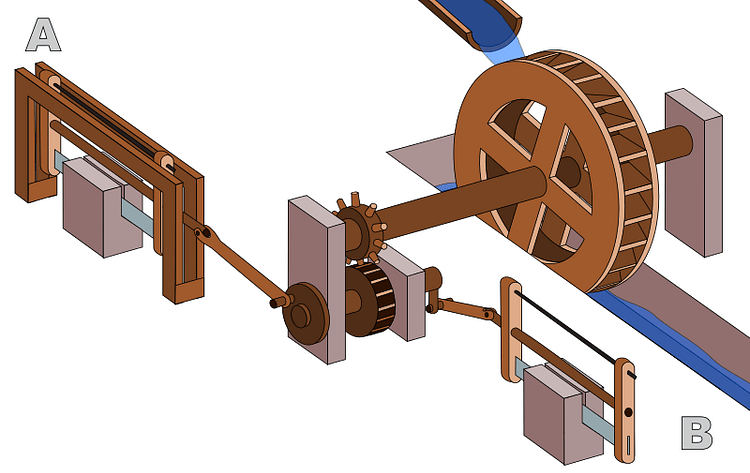

The Romans were great engineers and constantly strived to master the natural environment and test the limits of physics. Not only were aqueducts huge building projects (built up to 50 metres in height when spanning valleys and bringing water up to 100 km from its source) but they also employed many engineering tricks to aid water flow and increase purity: inverted siphons, stopcocks, settling tanks, aerating cascades, and mesh filters. Tunnels were constructed to provide more direct routes for aqueducts and roads, and excavated with surveying precision to enter and exit a mountain at precisely the desired spot. Watermills harnessed water power from rivers using sophisticated systems of wheels and gears and used the energy gained to drive mills for flour production, for saws to cut marble, or as ore crushers in search of precious metals.

Warfare and the fact that technological innovation very often guaranteed victory meant that the Romans sought to perfect such essentials of the ancient battlefield as siege engines and artillery weapons. Roman weapons fired bigger missiles, further and more accurately, than had ever been seen before. The mechanics of torsion machines was mastered, and they even devised ways to disassemble their artillery to easily move it to another place where it could be rebuilt and used again.

On the opposite side of human endeavour, the Romans also employed their engineering skills in the entertainment industry. Amphitheatres and circuses were architectural marvels in themselves, but they also contained all manner of mechanical devices to spice up public shows. Water organs played while chariots whizzed by, machines replicated thunderstorms, and hidden trapdoors appeared in arena floors to magically bring exotic and terrifying animals into the organised chaos of gladiator fights and battle re-enactments.

Geography

The Romans did not add very much to the Greek tradition of geography as a theoretical subject, but it did become a staple entry in their encyclopedias. Military commanders on campaign and regional governors were perhaps the Romans' greatest geographers as they mapped the areas of practical relevance to their roles. Pomponius Mela did attempt an exhaustive catalogue of the people and places of the known world, including the seas and places of historic interest in his mid-1st century CE De chorographia.

Mathematics & Geometry

Roman mathematics, as with earlier Greek views on the discipline, maintained a strong link with philosophy. Always interested in the practical application of theory, mathematics tended to focus, too, on natural phenomena and astronomy. The Romans not only applied mathematics to problems of architecture but also to such essential administrative tasks as tax accounting and land surveys. In addition, the pure mathematical subjects treated by Pythagoras and others were studied as part of a standard Roman education.

Perhaps one of the most recognisable features of Roman culture, and still widely used in the modern world, is the Roman system of numerals. Here I = 1, V = 5, X = 10, L = 50, and 1,000 was represented by M, an abbreviation of milla/mille (thousand). The system uses both addition and subtraction to represent figures (e.g. XX = 20 and IX = 9). The Romans also used fractions and certain numbers came to have special significance (e.g. 365) and even names could be translated into a representative number (famously that of Nero Caesar into 666)

Medicine

Perhaps the greatest contribution the Romans made to the field of medicine was to spread knowledge of medical matters through the publication of treatises and a greater accessibility of ordinary citizens to a professional doctor. The army had its own designated physicians, as did larger private homes. Doctors also became more ambitious in their surgeries, better equipped as they were with a greater array of specialised instruments which ranged from forceps to wound-retractors. Doctors were also able to gain valuable experience from dealing with war-wounded and those injured in the arena. Another innovation was the creation of dedicated hospitals within each army camp.

Medicines were produced and more freely available than previously, with pills often using plants and herbs, which included the use of morphine via extracted poppy juice. Through the greater study of the body from dissection, such internal injuries as kidney damage and spinal dislocations could be diagnosed accurately too, even if their cure was unlikely.